[Khrushchev] has an opportunity now to move the world back from the abyss of destruction ... by refraining from any action which will widen or deepen the present crisis -- and then by participating in a search for peaceful and permanent solutions...

— John F. Kennedy’s Speech on Radio and Television, October 22, 1962

JTT is proud to present Move the world back from the abyss of destruction, a presentation of objects that collectively search for meaningful and sustainable responses to man’s inherent desire to create. All the works in this show are impulsive, accumulative, specific, additive and as John Outterbridge describes, “anything at any given time.” These artistic forms oscillate from chaos to stillness, but all the while celebrates this animating creative force within humanity.

Offering, (1961) by Alfonso Ossorio is the first work on view. Friends with and collector of, Jean Dubufett, Clyfford Still, and Jackson Pollock, Ossorio began making abstract expressionist paintings in the 1950s alongside his peers. After visiting Dubufett in Paris he began to make assemblages like the two here on view. He referred to this new body of work as “congregations” to reiterate his belief in art as sacred ritual. In the same year Ossorio made Offering, he participated in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition The Art of Assemblage, which introduced his work to a wider public along with the broader concept of assemblage, where “banal, often tawdry materials retain their individual physical and functional identity, despite artistic manipulation.” more

On a plinth beneath Ossorio’s work are proto-examples of the assemblage tradition known as memory jugs. Generally understood to be descendants of West and Central African funerary practices, the creators of these 19th and 20th century objects are unknown. They consist of found objects pressed into a putty that has been plastered around an existing vessel. They are in the vein of Victorian tradition of scrapbooking insofar as they are cataloging objects for keep- sake. Scholar Brendan Greaves describes memory jugs as “homegrown answers to Duchamp’s notion of ‘delay’ (which he trapped in glass rather than in a ceramic jug.)... We can call—or curse—the tradition of making memory jugs ‘folk’ or ‘vernacular’ or ‘bricolage’... but that’s evading and segregating the accumulative act itself, the actual process of pressing into putty, the footprints of remembering.” more

Memory and ritual are both ongoing concerns in the work of Mike Kelley, the memory jug tradition itself is a known reference in his practice. Kelley’s interest in folk art centered on an engagement with formal techniques that might otherwise be disregarded. This can be seen in Foreground, background, (1990) an embroidery work that consists of a lone three dimensional crocheted woolen house sitting in front of a two dimensional wool quilt. The quilt depicts a flattened landscape with houses dotting rolling hills. This juxtaposition plays out as a tongue-in-cheek literalization of classic, if not hackneyed, discussion of figure-ground relationships in art.

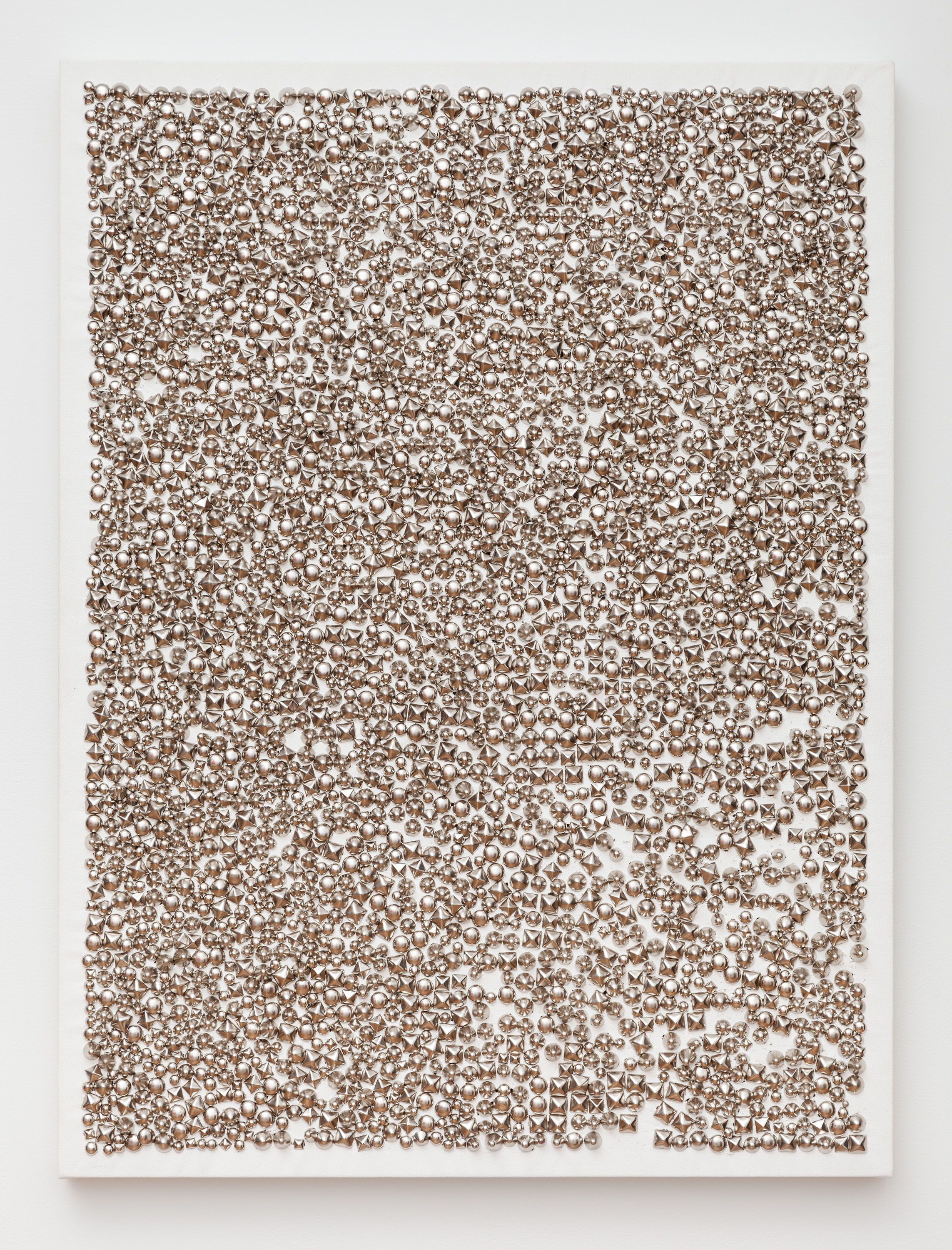

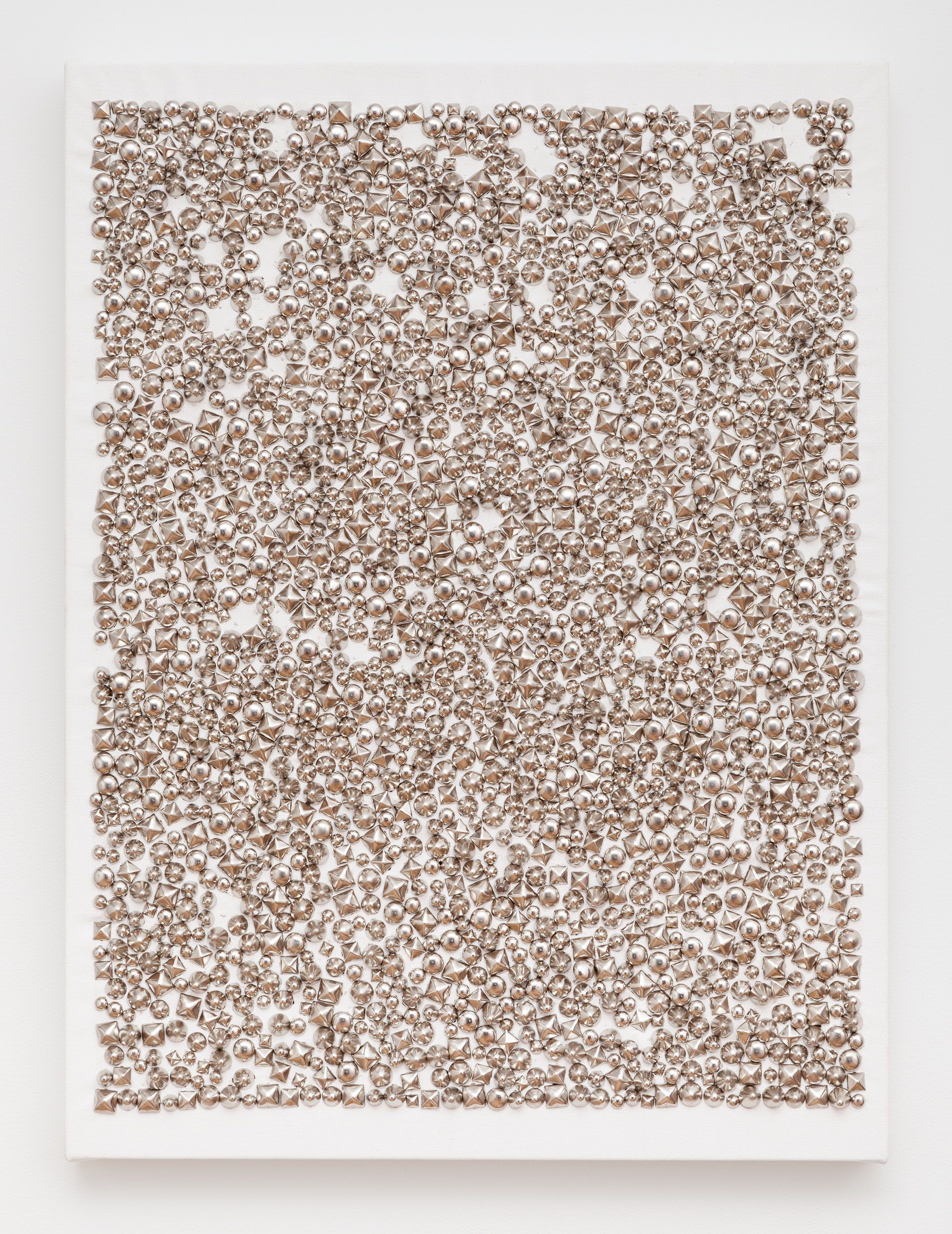

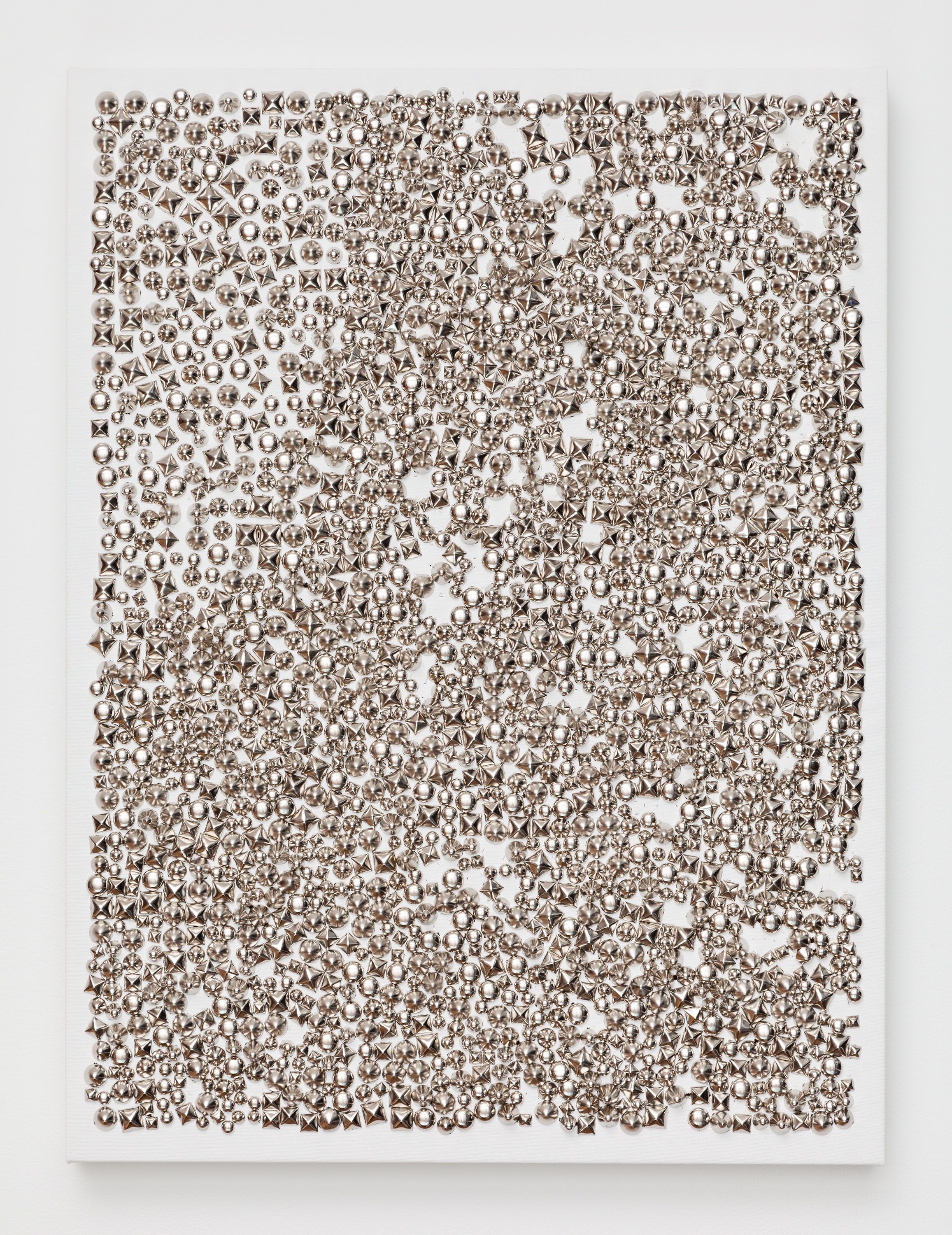

Above the Kelley, hangs a painting by Dan Colen made of studs, the iconic punk ornament, pressed into canvas. The studs trace an inverted asymptote, a decision making process where the further away from the starting point of the first stud that is placed, the more random the pattern appears, departing further and further from the perfection of the grid. Instead what is left is a cartographic image of the hand’s simultaneous proximity to order and chaos, a relevant technique given the studs’ transgressive history.

In the corner hangs an installation by Brooklyn-based performance artist Geo Wyeth titled Trap, (2014) that is activated upon approach: light bulbs affixed to the surface turn on and a soft vibration emits from a pillow laying on the floor. This installation is among a series of theatrical arrangements made of found materials that are essential to what Wyeth calls “Kitchen Steve”, a live set of theatrical tactics enacted by the artist intended to manifest a “constant becoming” as a means of rupture. From the top of the structure loosely hangs a gathering of hair, and its vertical placement in the corner between two walls gives it the sense of an alter—to whom or to what is left untold, but the engagement with the materials is inclusive.

Rag and Bag Idiom VI, (2012) is a wall sculpture by John Outterbrige. Outterbridge says of his “Rag Man” series, “I did a group of works that looked at the canvas, the fabric canvas, as being simply a piece of rag, depending on how you look at it. You pain on it, you stretch it. I didn’t want to stretch it around four corners; I wanted to stretch it around other forms, other formats... You’d disregard framing, but you’d fold the edges, protecting the composition in such a way that some other aesthetic notions started to introduce themselves.” more

The artists in this exhibition each belong to a trajectory of American history distinct from one another, yet all are equally valid in their approach to culturally charged materials and forms. And in their awareness of official history’s penchant to forget, they hold a stubborn faith in an object’s ability to conjure the forgotten.

JTT would like to thank Ellen Langan for her significant curatorial contribution.

I'm going back home to Georgia in a jug

by Brendan Greaves

Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, Philadelphia, December 27, 2007

Offering, 1961

plastic and mixed media

68 x 18 x 12 in

172.5 x 45.5 x 30.5 cm

Courtesy of the Ossorio Foundation

Offering, 1961

plastic and mixed media

68 x 18 x 12 in

172.5 x 45.5 x 30.5 cm

Courtesy of the Ossorio Foundation

Foreground, background, 1990

embroidery in two parts

27 x 33 x 4 in

68.5 x 84 x 10 cm

Dajjal, 2013

studs on canvas

30 x 22.5 in

76 x 57 cm

Spigot, 1971

plastic and mixed media

42 x 14.5 x 16 in

106.5 x 37 x 40.5 cm

Courtesy of the Ossorio Foundation

Window With Footnote, 1991

mixed media

38.25 x 22 x 14.5 in

97 x 56 x 37

The Fifth Century, 2013

studs on canvas

24 x 18 in

61 x 45.5 cm

Trap, 2014

mixed media

dimensions variable

Trap, 2014 (detail)

mixed media

dimensions variable

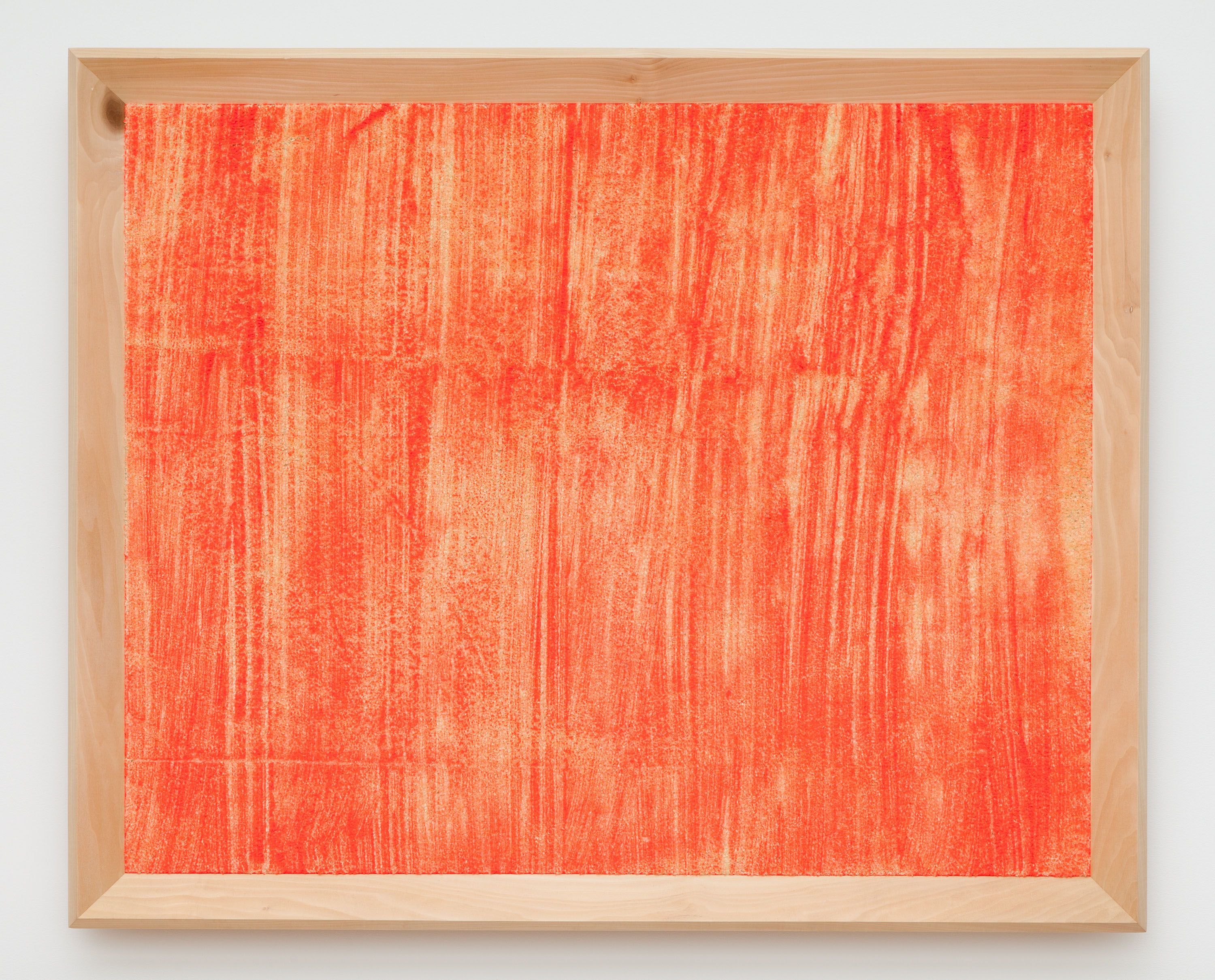

Carpet # 2, 2003

acrylic on carpet, framed

49.5 x 40.5 x 4 in

125.5 x 103 x 10 cm

various media on ceramic jug

13.5 x 4.5 x 4.5 in

34.5 x 11.5 x 11.5 cm

various media on ceramic jug

12.5 x 11 x 11 in

32 x 28 x 28 cm

Rag and Bag Idiom VI, 2012

mixed media

15 x 12 x 6.5 in

38 x 30.5 x 16.5 cm

Turkish, 2014

studs on canvas

24 x 18 in

61 x 45.5 cm