JTT is proud to present three sculptures by JO NIGOGHOSSIAN (B. 1979) for the THENnow section of MiArt, Milan. Each work is engaged in traditional portraiture as well as an experimental study of the ways in which power manifests itself in architectural structures. Nigoghossian manipulates her materials, here for example steel and neon, as a means to study the space occupied by thought, mood, and capability.

Two of the works on view loosely splice the classic still life into an architectural and figurative dimension. In one case, a cross legged side table sprouts a bunch of spring flowers, in the other, a figure submissively kneels with two protrusions of diminishing hors d’oeuvres. The third, slightly earlier piece, based on a solitary otter and the Riviera Casino’s exterior lights takes on a tighter form — the neon is compartmentalized and confined. The layered and tiered structures of all the works in this grouping continue an exploration of space and shifting temperaments.

BILL WALTON (1935-2010) was born in Camden, New Jersey. After serving in the Navy as an electronics technician during the Korean War, he briefly studied at the Institute of Design in Chicago.

In 1958, Walton moved to the Philadelphia area where he worked as a commercial printmaker, a trade that was passed down to him by his father. Interested in the materials used for printmaking–wood, lead, steel–more than the finished product, Walton was poised for a life-changing experience when, in 1964, he visited an exhibition of minimal sculptural works at a local museum. Some years later, he recounted that he had gone home that afternoon and changed the occupation listed on his driver’s license from “commercial printer” to “artist.”

Over the course of more than forty years, Bill Walton made an exceptional and poetic body of work using common materials such as floorboards, wisteria branches, and paper napkins from his favorite diner, while employing simple gestures like stacking, folding, and turning. In this sense, he adopted the formal language of Minimalism, yet his works are also highly personal, handmade and small-scale. He chose never to date his work, believing rather that it was always in process and that materials were informed by their own histories, which they would bear even as they were subjected to subtle transformations. As such, Walton’s works share characteristics with Arte Povera and process art.

Walton was an avid fly fisherman and traveled each year to new rivers and streams, taking concise notes along the way that described the landscape and his experience. “Morris Run,” he once wrote, “it joins the stream somewhere close past the flats–But I’ve never seen it.” Relationships of all kinds, from man to nature, rock to water, path to road, figure prominently. “They cross each other. Run alongside you or veer off in odd directions. It is hard to know which one will take you where.” As metal gently twists around a piece of wood or cloth drapes over painted plywood, the work distills those special places and relationships as much as it celebrates the beauty of everyday objects.

Spring Flowers, 2015

steel, neon, rubber

55 x 54 x 24 in

139.5 x 137 x 61 cm

Hors d’oeuvres, 2015

steel, iron, neon tubing, transformer, wiring

24 x 60 x 54 in

61 x 152.5 x 137 cm

Solitary with light compartment, 2014

steel, neon

21 x 48 x 21 in

53.5 x 122 x 53.5 cm

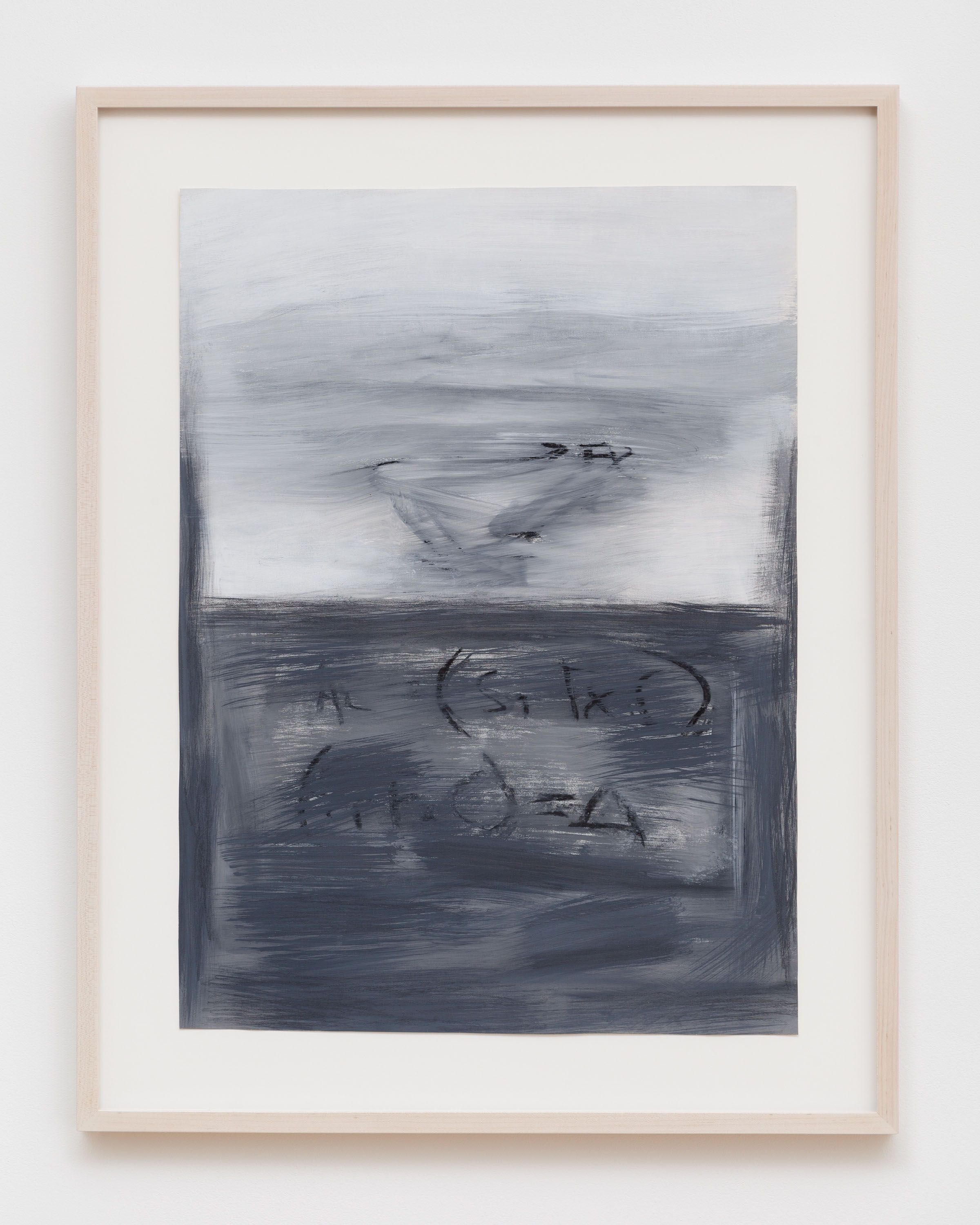

Title Unknown, n.d.

charcoal, paint on paper

28.5 x 21 in

72.5 x 53.5 cm

Sweet Lou & Marie #8, n.d.

linen, paint, wood

8 x 8 x 1 in

20.5 x 20.5 x 2.5 cm