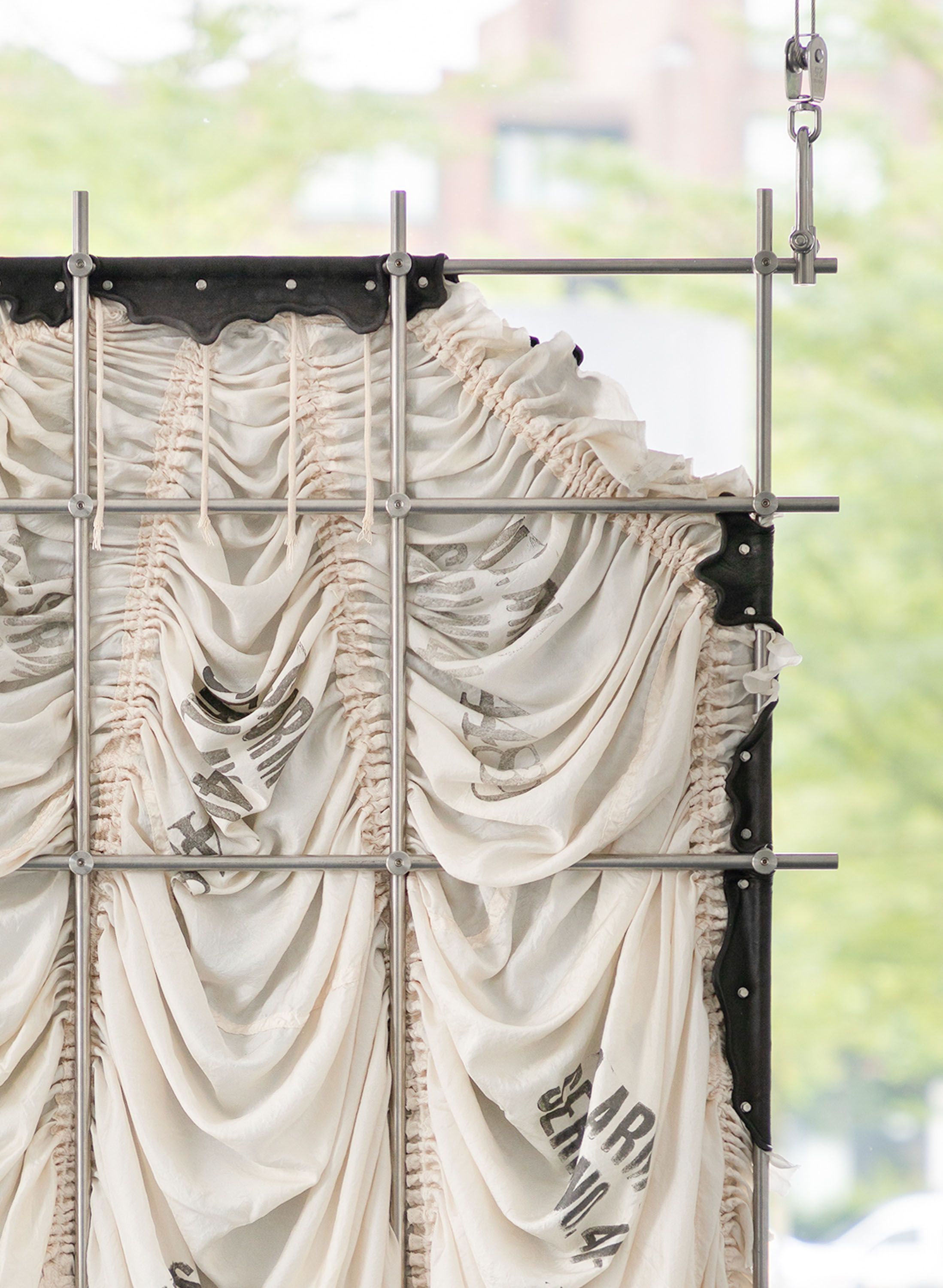

Eight straitjackets for parachutes. ‘Tamed’ by Cameron-Weir —draped, clamped and heaped —the parachutes all carry letters and numbers signaling their affiliation with the US Army in World War II. Acquired at auction on an online platform for war memorabilia, they are original equipment provided for military parachutists during the 1940s. The rapid development of aerial deployment strategies coincided with the technological advancement of airplanes during the war, which required the ability to drop a large number of soldiers at once.Now it seems as if a troop of paratroopers has fallen from the sky into the Dortmund Kunstverein: the parachutes, emblems for their carrier’s (absent) bodies, are imprisoned, much like Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Teresa von Ávila (c. 1650), locked within the marble architecture of Rome’s Santa Maria della Vittoria, cast in a moment between ecstasy and pain; life and death. The exhibition’s title, exhibit from a dripping personal collection, creates a poetic image evoking corporeality and psychic states, the words “dripping”and “personal”suggesting the feeling of a melting interior.

Cameron-Weir’s reduced setting at the Dortmund Kunstverein introduces a new focus. Eight similar stainless-steel constructions, each with five horizontal and four vertical bars, provide a lattice framework for parachutes that have been fixed to or wedged within the structure.The reverse side of these cream-colored parachutes has been bound to black leather, the edges protruding from the top and sides and pierced by bolts. The metal bars, like those used in scientific laboratories, form a cross shaped, cage-like grid; the parachute unfolds, in contrast, like an elegant curtain. The drapery becomes somewhat theatrical in its details, Baroque even. But only for a moment before the unyielding strictness of the metal prevails. The parachute’s sewn seams call to mind the patterned construction of a garment, and the sculpture seems like an oversized corset, like a sort of straitjacket.

Inside the exhibition space, Cameron Weir’s sculptures are fixed to the walls and hanging in the air, all arranged as pairs suggesting an object and its reflection. The floating sculptures have been stabilized by pulleys, steel cables, and sandbags, illustrating the effects of gravity. This floating or hanging in space thus suggests the fundamental principle behind the parachute’sfunction, with gravitation being omnipresent in Cameron-Weir’s exhibition as a deliberately applied, formative physical force: it is a basic conditionfor our being, provides a creative energy for sculpture, and is a force utilized throughout scientific research. In an interview with Natalie Bell within the framework of Cameron-Weir’s 2017 exhibition at the New Museum, viscera has questions about itself, the artist states how much the reflection upon core sculptural questions preoccupies her: “At a certain level sculpture has to work, it has to stand up or be hang in some way like you have to think about that all the time […]”. Here, in Dortmund, the sculptures’ material, form and content form a perfect fusion, providing an aesthetic density that develops over time in observation.

Using the vocabulary of seriality and questioning foundational conditions of sculpture —in this context, reflecting on the artist Eva Hesse (1936 –1970), Cameron-Weir steps beyond anti-expressionism and the rigidity of form. By selecting objects that reference diverse technologies, combining new industrial materials with objects bearing a particular history and a recognizable form –in this case, the parachute —her work points to the implications and consequences of mankind’s evolution. Cameron-Weir’s works instigate an inner journey into collective memory as well as alternative visions of the future. She appears as if a futuristic alchemist, prompting us to reflect on technological developments up to now and the associated post-human era. An ambivalence and irresolvable tension between technological development –often linked to war –and the potential peace and pain of the physical body draw us into the work of Elaine Cameron-Weir.

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather, sandbags

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather, sandbags

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather, sandbags

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm

parachute silk, stainless steel, leather, sandbags

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 63 x 36 x 7 in

dimensions variable; panel dimensions: 160 x 91.5 x 18 cm