Apollo Magazine

New York Times

Artsy

JTT is pleased to present an installation by Doreen Garner designed by the artist specifically for Art Basel. Garner’s sculpture and performance work engages the history of medical experimentation on black women’s bodies in America. By refusing to relegate this history into a depoliticized record of the past, Garner emphasizes the problematic relationship of medicine and race that persists today.

This presentation focuses on Dr. James Marion Sims, an American physician who specialized in gynecological surgery. His most significant work was to develop a technique for the repair of vesicovaginal fistula, an abnormal or surgically made passage between the bladder and the vagina that was a catastrophic complication of childbirth during the 19th century. From 1845 to 1849, Sims performed gruesome experiments on enslaved and purposefully unanesthetized women until he developed a surgical technique to repair the fistula successfully. Sims was not only lauded for his achievement in developing this surgical technique, journals that detail his procedures are considered important medical documents to this day. In these journals, Sims erroneously claimed that black women had a higher tolerance for pain and thus didn’t require anesthetic. Contradictorily in other areas of his journal he claimed that anesthetics weren’t available at the time of his procedures. Many medical students have read Sims’s journals over the past century as a part of their education which may contribute to the following study reported by the New York Times in April of this year:

“In 2016, a study by researchers at the University of Virginia examined why African-American patients receive inadequate treatment for pain not only compared with white patients but also relative to World Health Organization guidelines. The study found that white medical students and residents often believed incorrect and sometimes “fantastical” biological fallacies about racial differences in patients. For example, many thought, falsely, that blacks have less-sensitive nerve endings than whites, that black people’s blood coagulates more quickly and that black skin is thicker than white. For these assumptions, researchers blamed not individual prejudice but deeply ingrained unconscious stereotypes about people of color, as well as physicians’ difficulty in empathizing with patients whose experiences differ from their own. In specific research regarding childbirth, the Listening to Mothers Survey III found that one in five black and Hispanic women reported poor treatment from hospital staff because of race, ethnicity, cultural background or language, compared with 8 percent of white mothers.”

Sims’s medically sanctioned violence is not an example of a distant history that we have progressed away from—it is an active influence on contemporary medical practice that Garner is invested in exposing.

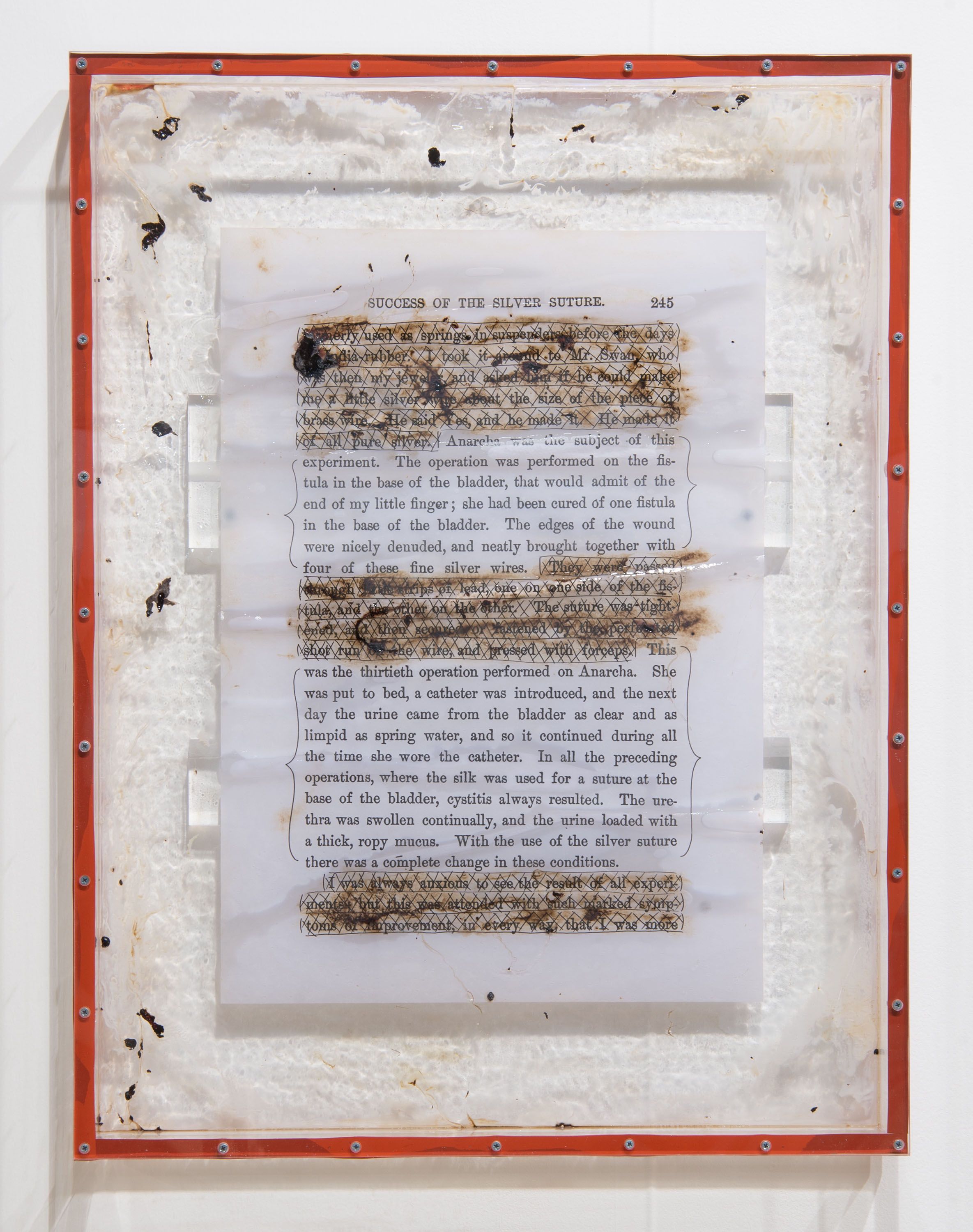

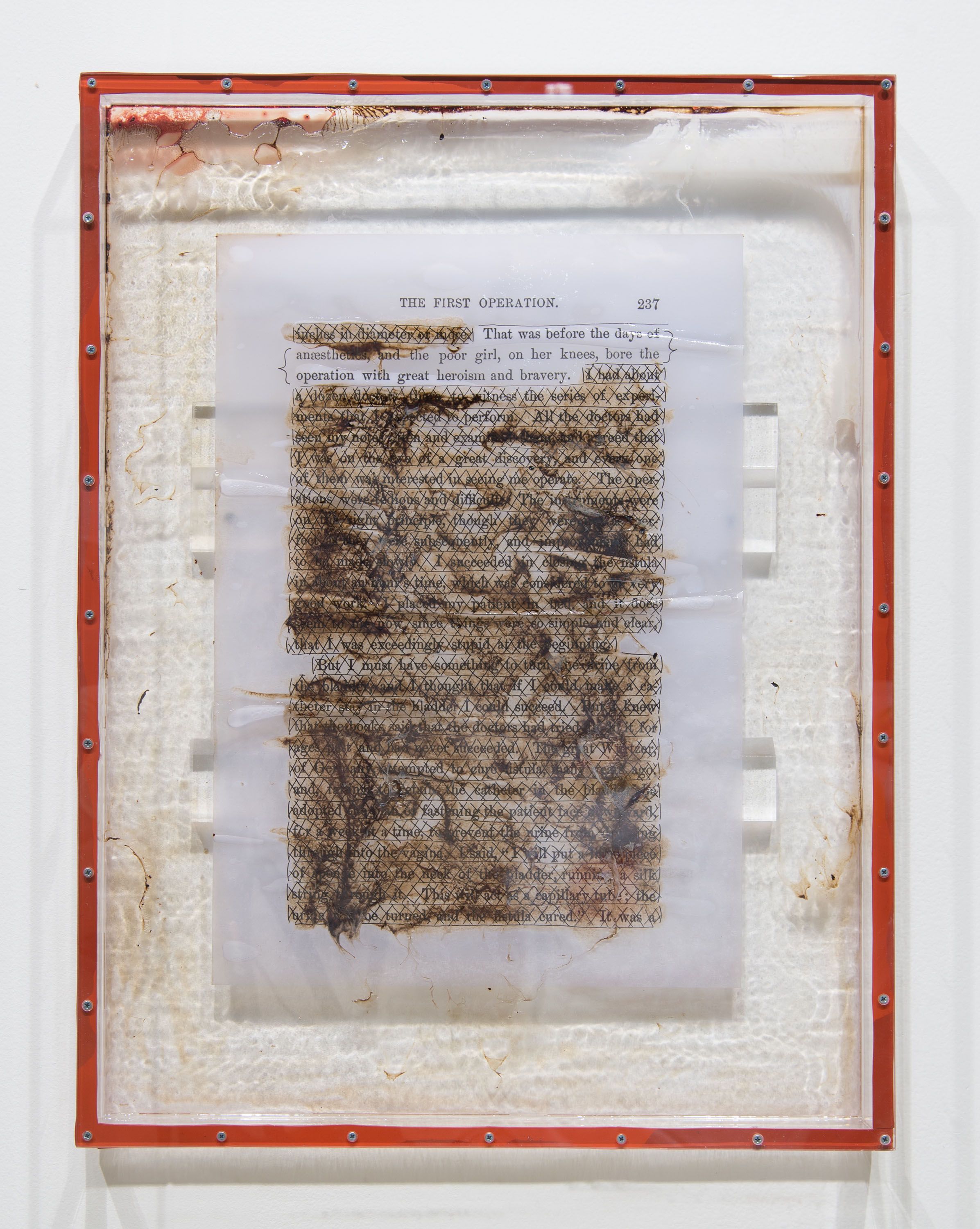

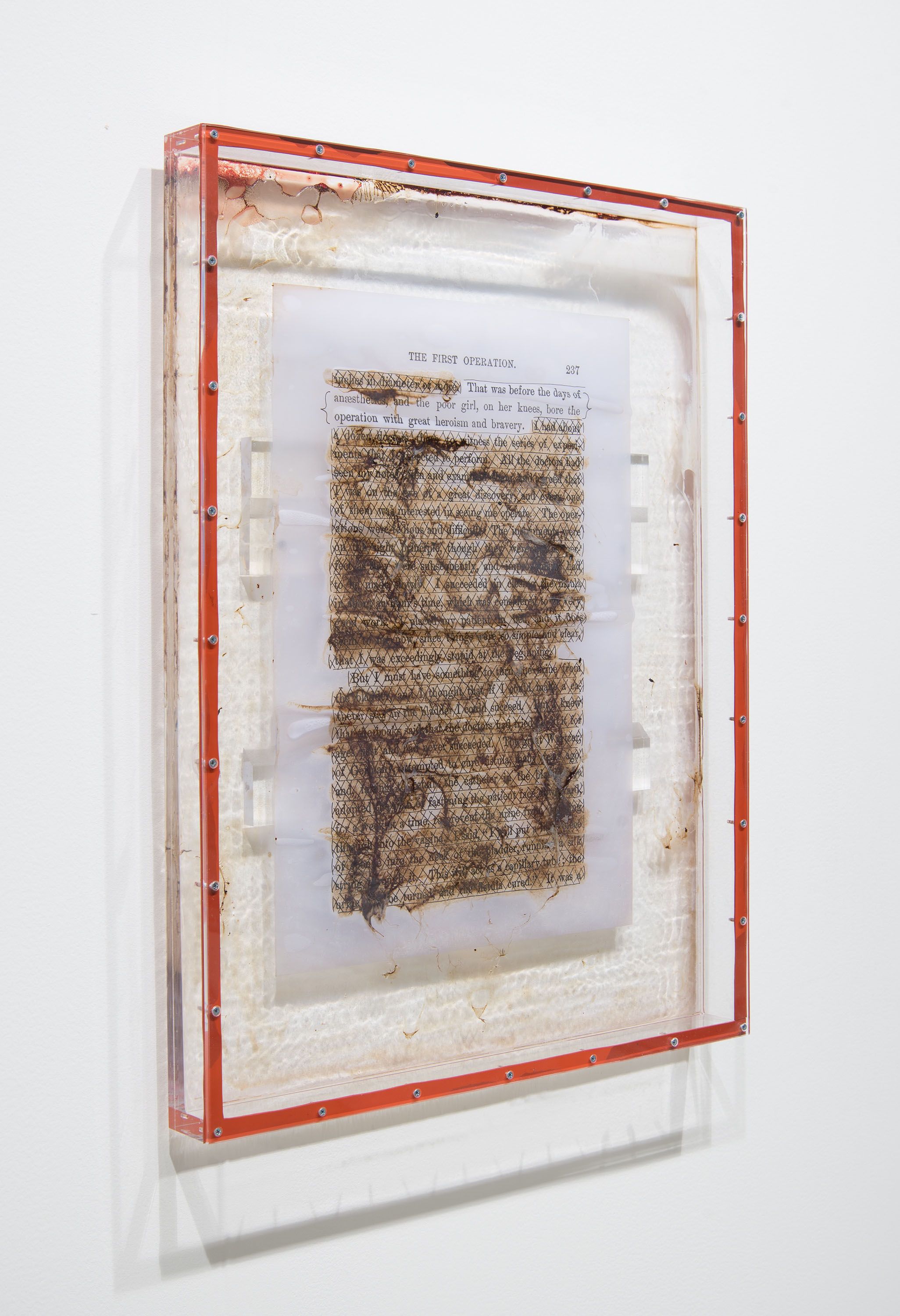

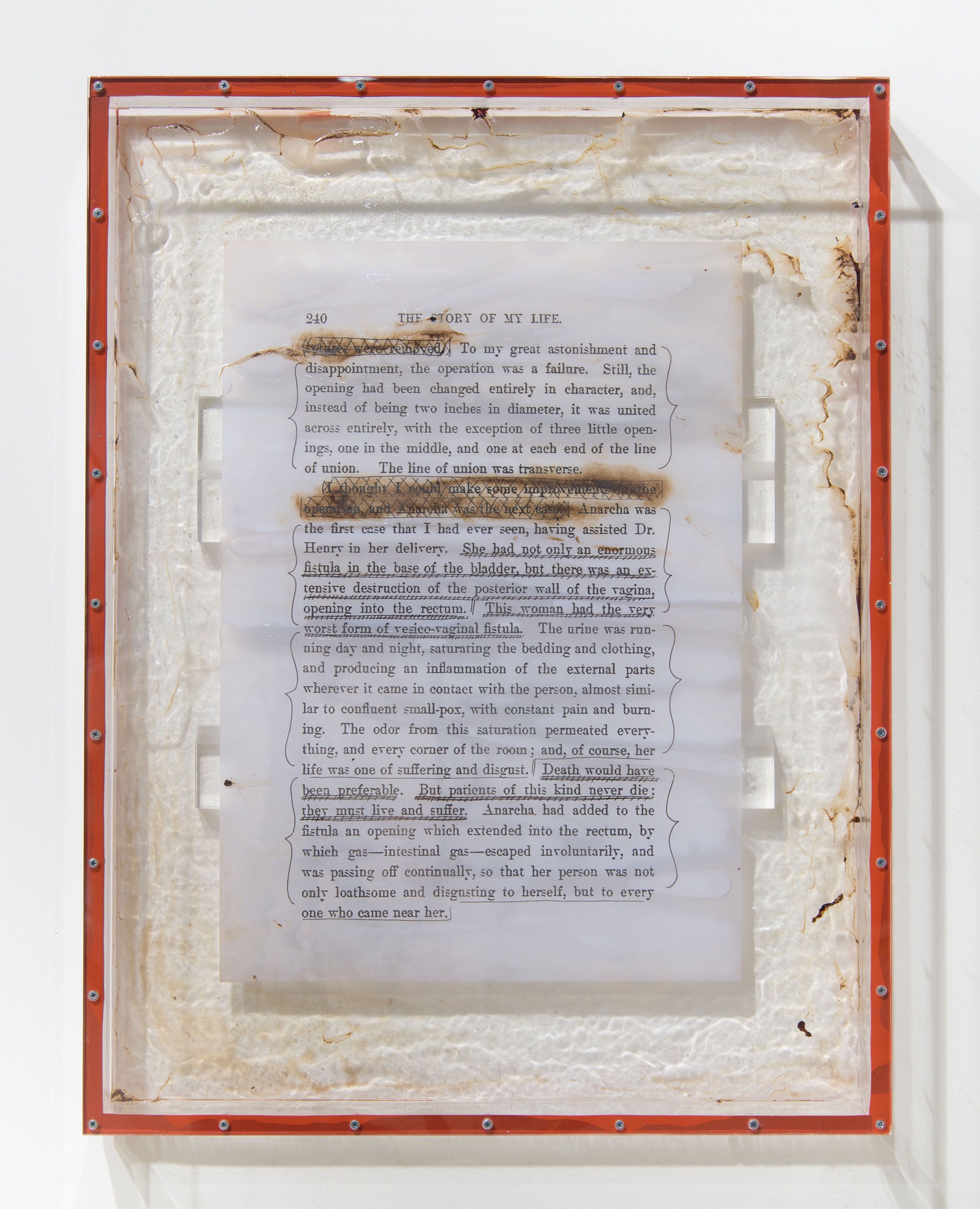

Along one wall of Garner’s Statements presentation are three plexiglass vitrines. In these vitrines, copies from Sims’s journal oat inside a thin layer of resin. Garner has strategically contaminated these pages with menstrual blood and urine over areas that she wishes to sensor from the already obfuscated journal page. The pain of Anarcha and Lucy—two of only three known slaves subject to Sims’s abuse—is remembered through these works. Garner’s reliquaries are an opportunity to reflect on the pain of these women, sanctifying them and retrieving their histories from the grasp of Sims. There is a profound power in simultaneously exposing and denying Sims’s oppressive authorship.

On the opposite wall hangs, Red Rack of those Ravaged and Unconsenting 2018, a large metallic structure lined with red fluorescent bulbs. Dangling from hooks at its center are multiple oblong sculptures made of silicone body parts sutured together with staples, marbleized silicone, expanding foam, fiberglass insulation, a protective layer of sharp needles, and an array of meticulously arranged beads. Each of these abstract forms are about the size of a human torso, but their forms are also akin to a single oversized organ. The site of these fragmented bodies alludes to the process of cutting open a body and suturing it back together, a representation of the dehumanization that black bodies have experienced throughout history. The materials that Garner employs in the figurative element of this work such as fiberglass insulation and expanding foam refer to a discovery made in 1989 when the 154-year-old Medical College of Georgia was renovated. Beneath the basement of the school, almost 10,000 human bones and skulls bearing the marks of nineteenth-century anatomy tools were uncovered. An unprecedented influx of students into medical schools of the mid-1800s led to an exceptional need for cadavers. Thus, the Medical College of Georgia began to routinely abduct corpses from the Cedar Grove Cemetery, an African American cemetery, between 1835 and 1912. It was also later discovered that many schools in the North had performed similar grave robberies for the advancement of medical profit. Author Harriet A. Washington describes the trouble that this brought for black people in her book “Medical Apartheid:” “For blacks, anatomical dissection meant even more: It was an extension of slavery into eternity, because it represented a profound level of white control over their bodies, illustrating that they were not free in death.” Garner is committed to portraying an abjection of the black body that speaks to the actual lived experience of black people and is often omitted from Art History.

stainless steel bars, fluorescent lights, wiring, silicone, insulation foam, glass beads, fiberglass insulation, steel hooks, steel pins, pearls

64 x 114 x 32 in

162.5 x 289 x 81.5 cm

stainless steel bars, fluorescent lights, wiring, silicone, insulation foam, glass beads, fiberglass insulation, steel hooks, steel pins, pearls

64 x 114 x 32 in

162.5 x 289 x 81.5 cm

stainless steel bars, fluorescent lights, wiring, silicone, insulation foam, glass beads, fiberglass insulation, steel hooks, steel pins, pearls

64 x 114 x 32 in

162.5 x 289 x 81.5 cm

stainless steel bars, fluorescent lights, wiring, silicone, insulation foam, glass beads, fiberglass insulation, steel hooks, steel pins, pearls

64 x 114 x 32 in

162.5 x 289 x 81.5 cm

plexiglass, rubber, inkjet print on paper, menstrual blood, urine, epoxy resin

25 x 19 x 2.5 in

63.5 x 48.5 x 6.5 cm

plexiglass, rubber, inkjet print on paper, menstrual blood, urine, epoxy resin

25 x 19 x 2.5 in

63.5 x 48.5 x 6.5 cm

plexiglass, rubber, inkjet print on paper, menstrual blood, urine, epoxy resin

25 x 19 x 2.5 in

63.5 x 48.5 x 6.5 cm

plexiglass, rubber, inkjet print on paper, menstrual blood, urine, epoxy resin

25 x 19 x 2.5 in

63.5 x 48.5 x 6.5 cm