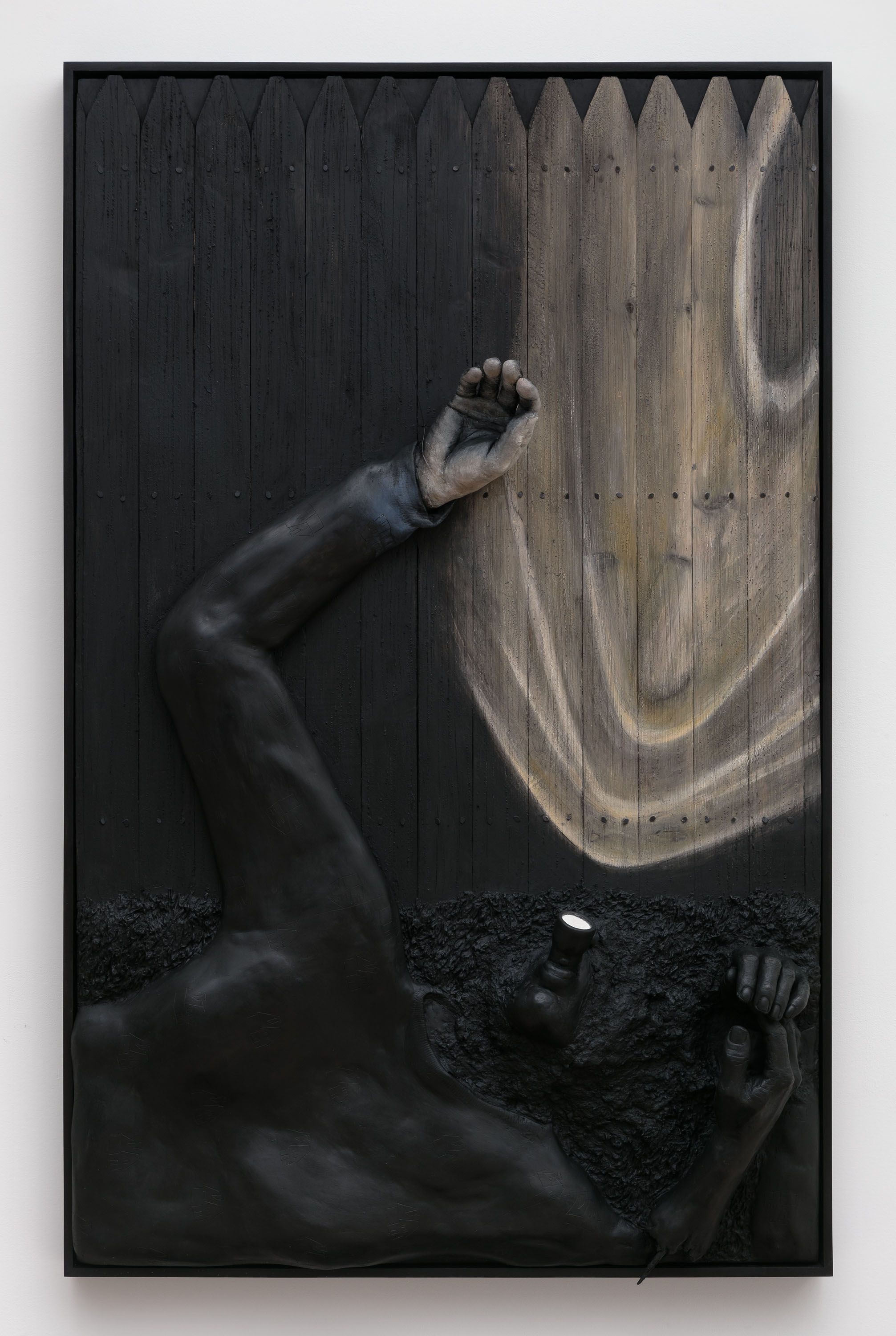

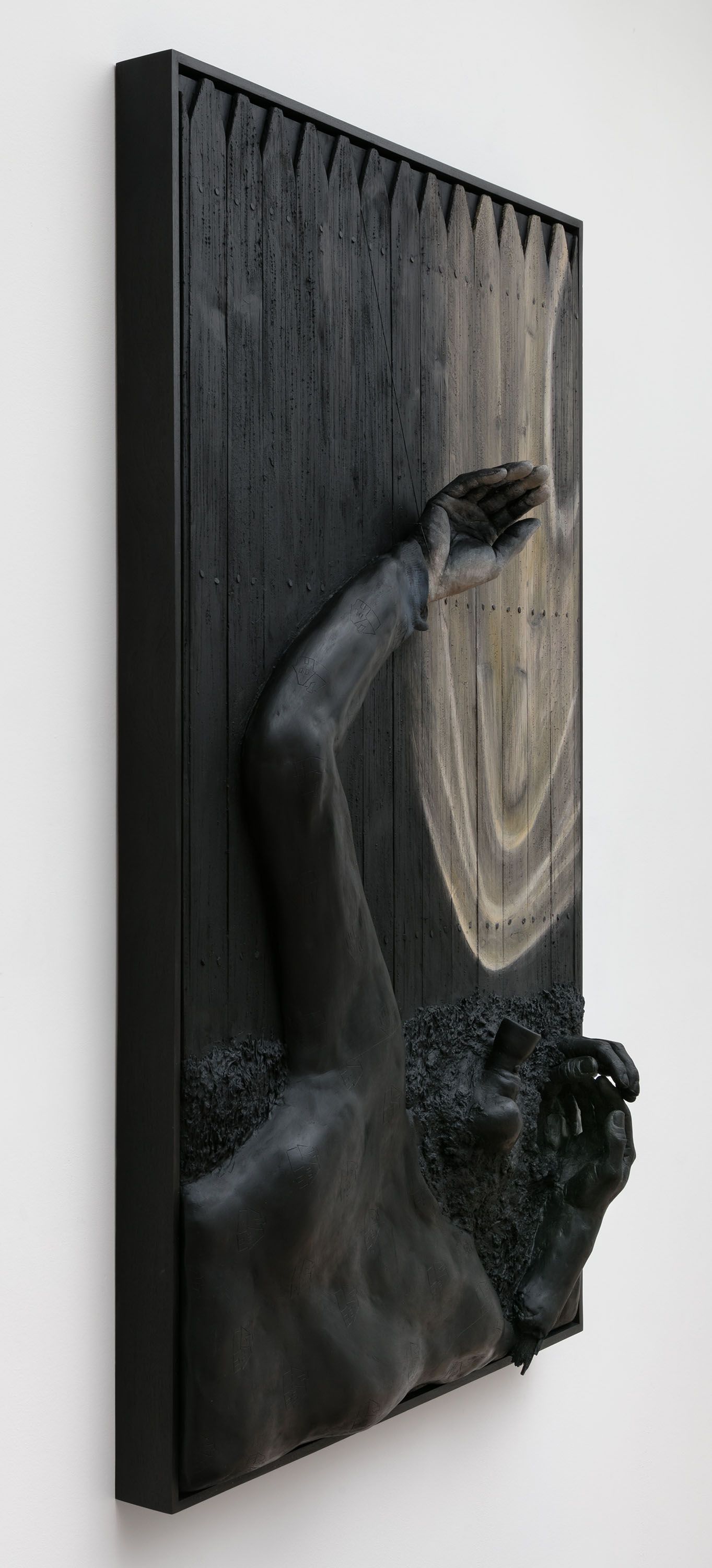

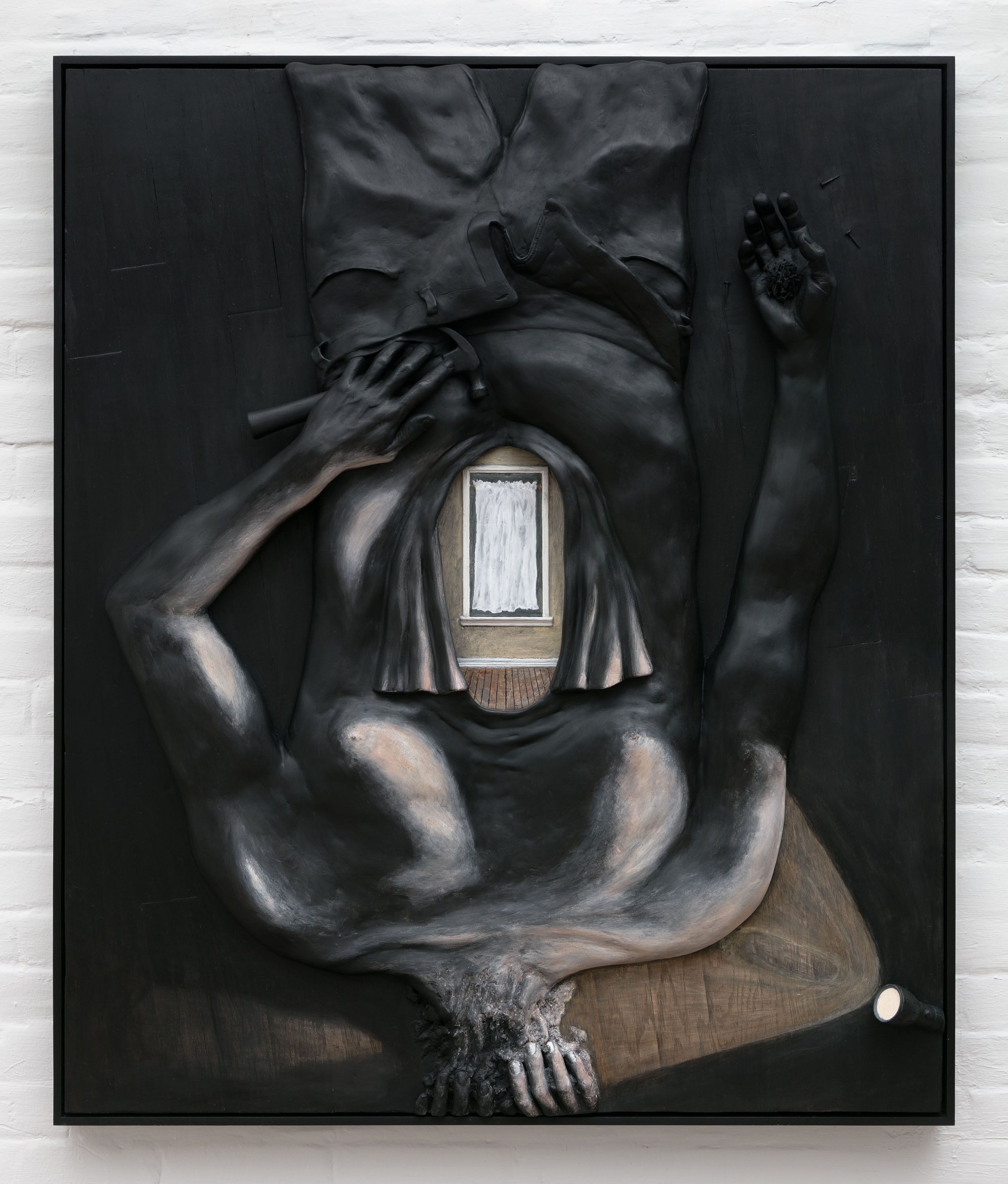

JTT is pleased to introduce a new series of work by Dan Herschlein. Titled Night Pictures, these four mid-relief wall panels made from wood, plaster and wax depict darkened scenes of partial bodies illuminated by flashlight beams. Building on the tradition of 20th-century American painters like Grant Wood and Andrew Wyeth, Herschlein portrays a normalized version of horror; a banal uncanniness that hints at an unsettled history.

Each panel portrays a different view of the strange happenings in and around a house: in one, curious scarecrow-like figures line up at a fence peering towards a structure while in another, a torso lies on the floor of the interior, its chest peeled back to reveal a lit room. A velvety application of black wax creates the darkness that envelops the majority of the picture plane, while small areas of color appear illuminated by a flashlight or a glowing window. Whereas spotlights normally serve to highlight something of importance, the lit portions of these pictures offer a distraction from a more interesting event outside of its glow. In an attempt to disrupt hierarchical associations of light and dark, the notable action occurs in areas of darkness.

Central to Herschlein’s work are figures partly cast from his own body that approach thresholds or borders, as they themselves also display states of transition. In this new series, he continues this application of body horror as a means to convey the more visceral aspects of emotion and how emotions haunt bodies. Herschlein’s work calls into question why we find certain imagery unsettling and suggests a link between fear and heavy, untapped emotions. Headlessness implies automation and unconsciousness. At a glance, the figures in Night Pictures might be read as destructive, even violent, but a closer look reveals their gestures of comfort, construction, and struggle. In Night Picture (Hold Me Together), the figures at the fence grasp at each other’s hands as if for reassurance. In another panel, these are shown to be scarecrows, built or conjured by an unseen maker, and one has crumpled to the ground. Rather than performing their usual function of frightening away intruders, they appear to be coming to visit. Another gesture of care is evident in Night Picture (A Noise in the Room Next Door), where hands at the neck imply a maker’s presence, preparing to sculpt his figure’s head.

As Herschlein reproduces his own likeness in varying stages of wholeness, he also suggests the existence of an unseen maker who builds and cares for the partial bodies. This aspect of his practice recalls a therapeutic tactic: in order to cultivate self-compassion, treat yourself as you would a friend. The fact that the figures are splintered and obscured by darkness speaks to the trials of caring for oneself regardless of the condition we’re in. Rather than send these visions away, Herschlein imagines the possibility of inviting them in.

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, milk paint, wax, graphite

49 x 30.5 x 7.5 in

124.5 x 77.5 x 18.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, milk paint, wax, graphite

49 x 30.5 x 7.5 in

124.5 x 77.5 x 18.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, milk paint, wax, graphite

49 x 66.5 x 7 in

124.5 x 169 x 18 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, milk paint, wax, graphite

49 x 66.5 x 7 in

124.5 x 169 x 18 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, milk paint, wax, graphite

49 x 56 x 5 in

124.5 x 142 x 12.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, milk paint, wax, graphite

49 x 41.5 x 6 in

124.5 x 105.5 x 14.5 cm