Artforum

Air Mail

The Art Newspaper

Cultured

THEGUIDE.ART

JTT is pleased to announce Dweller, Dan Herschlein’s third solo show with the gallery.

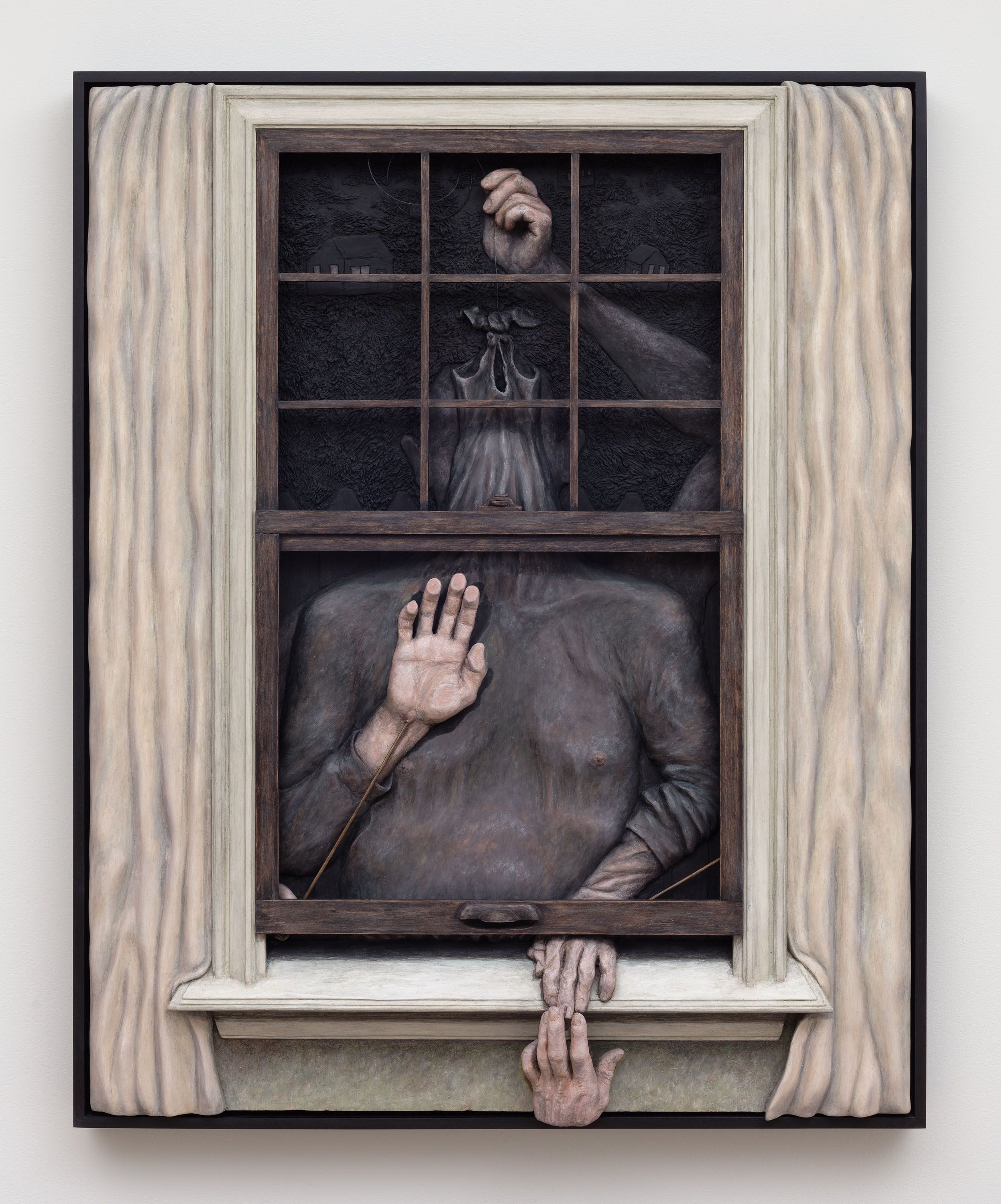

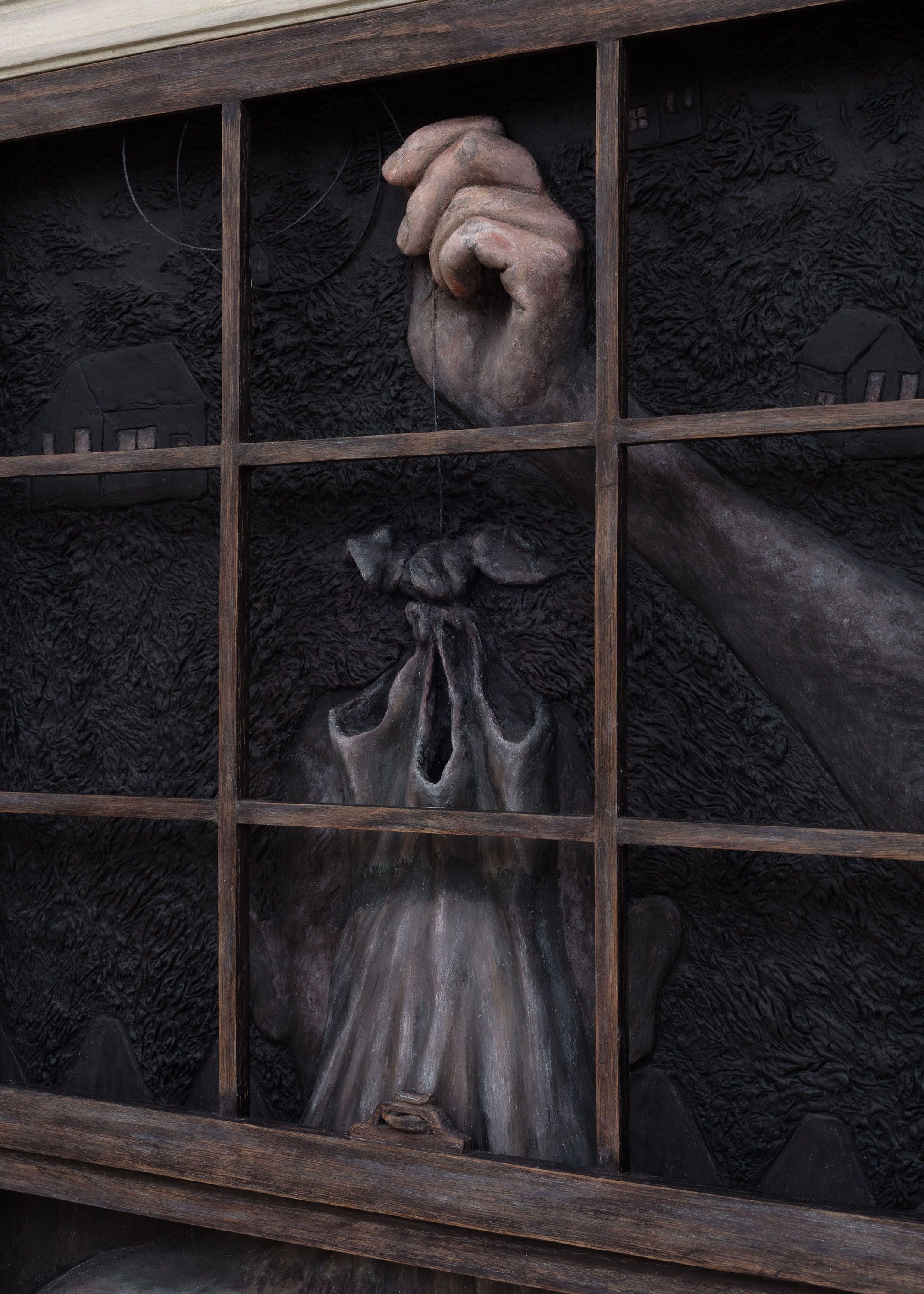

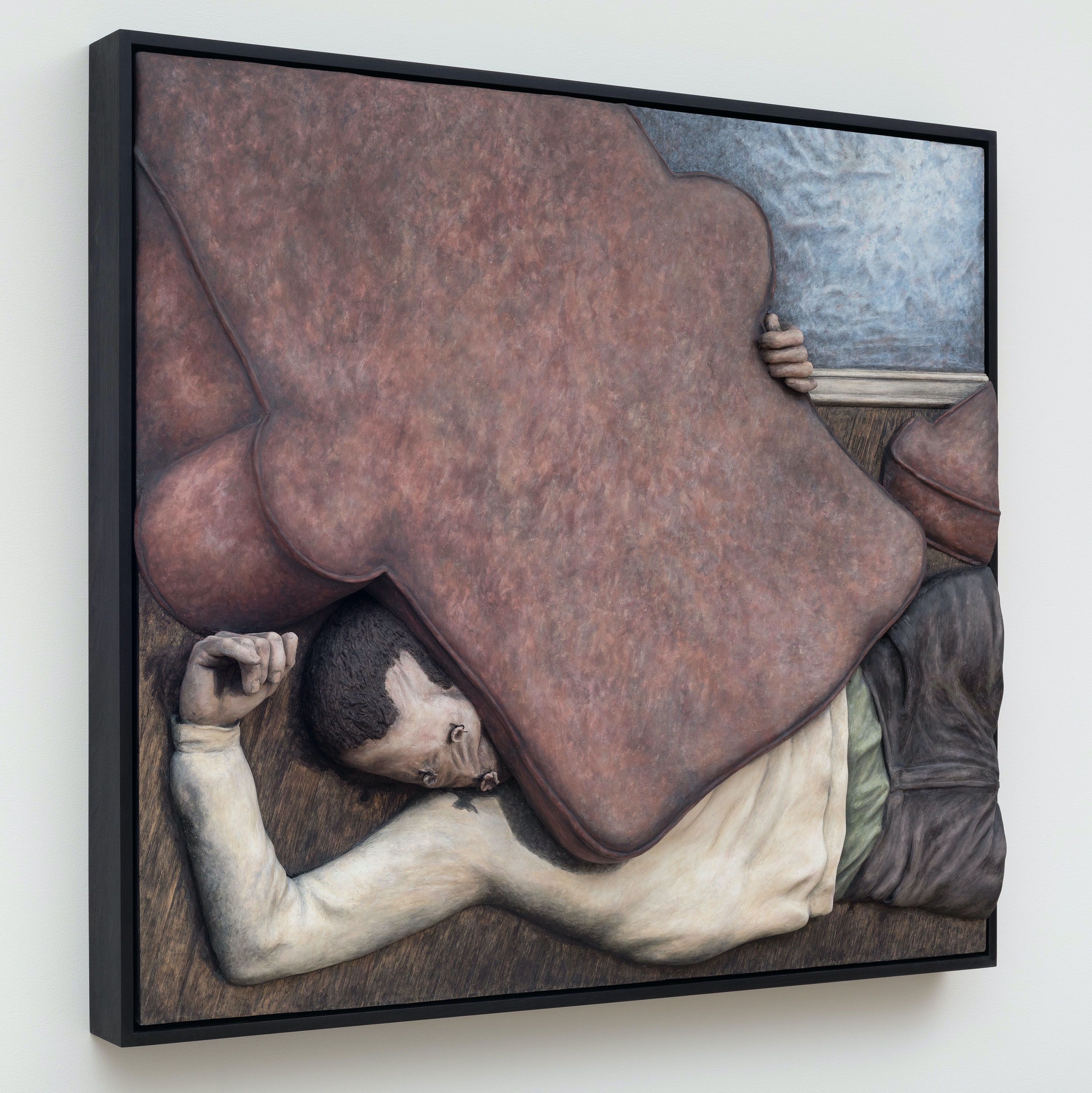

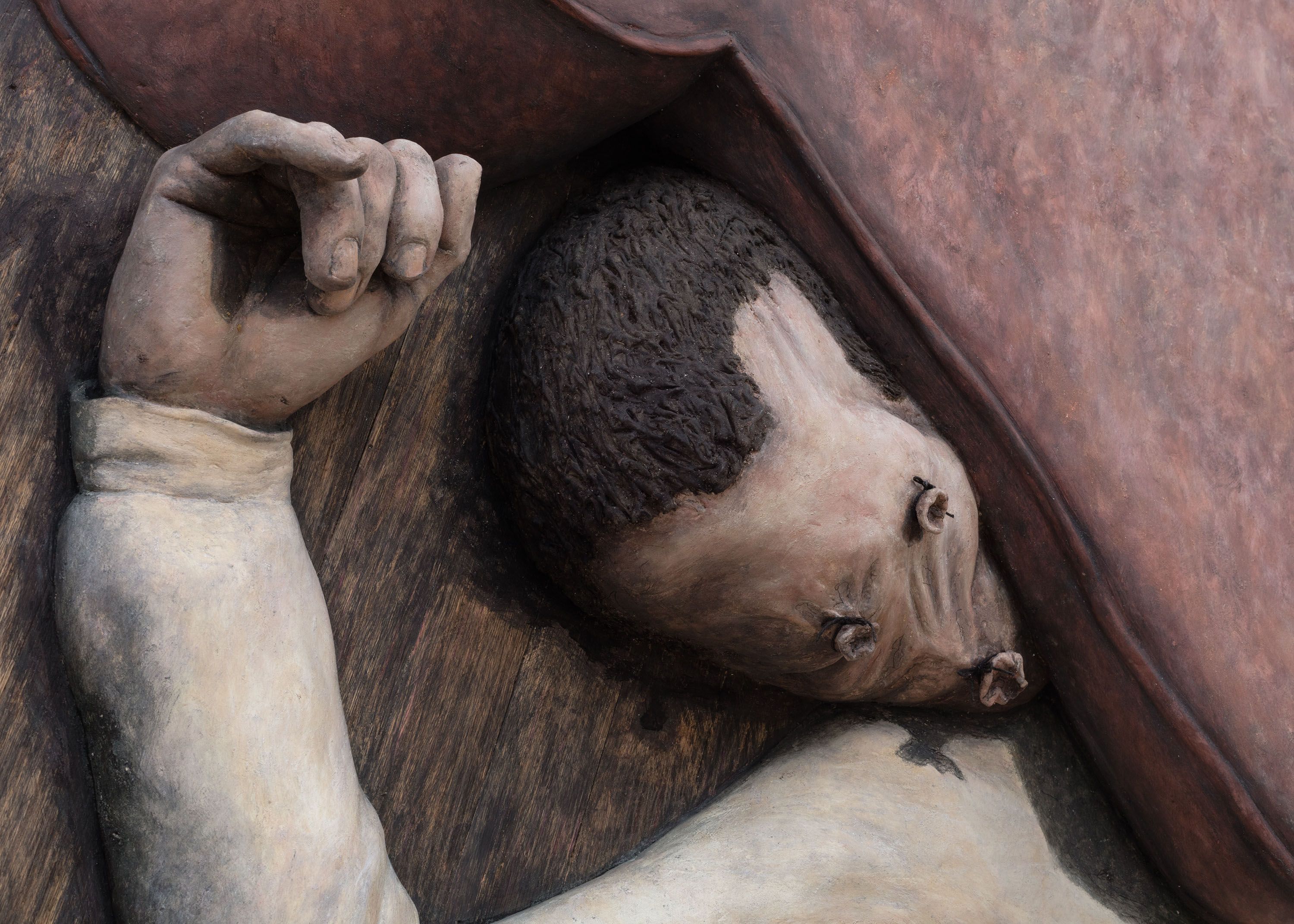

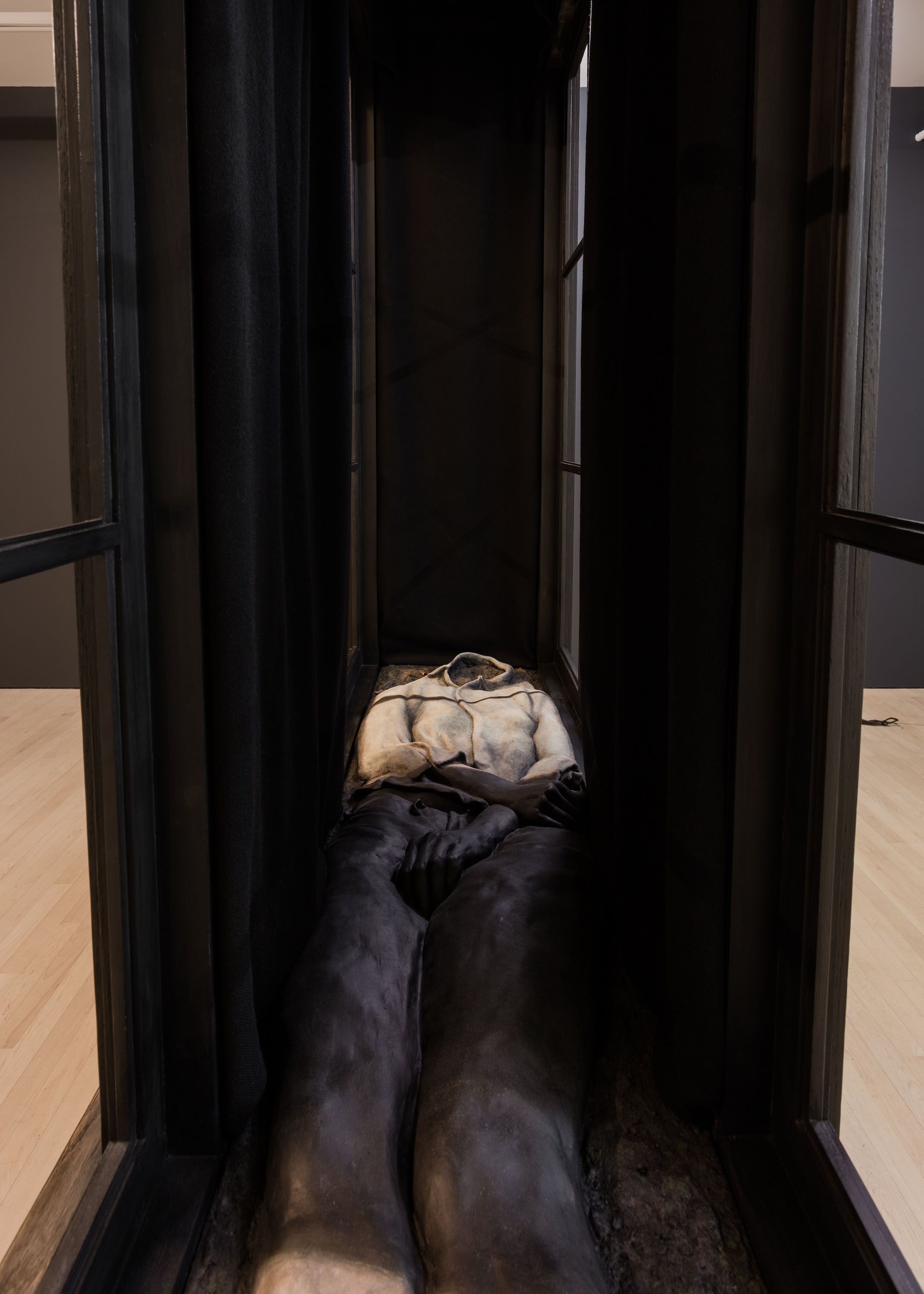

On view are a series of intricately painted plaster reliefs portraying scenes from a private interior life. An abbrevi- ated segment of a house, that follows the logic of his Night Pictures, complete with siding, windows and deep black wax, bisects the adjacent gallery. Herschlein’s larger practice renders the interior and exterior of domestic spaces with great detail in accordance with a supernatural logic. By appropriating tropes from horror cinema and gothic fiction, Herschlein explores aspects of narrative identity as an efficient tool for self-deception, and the lengths an individual may unconsciously go to in order to craft and mediate their own narrative.

One relief, titled The Dinner Companion, depicts an overhead view of a dining table with two place settings fac- ing one another. A meal of meatloaf, mashed potatoes and asparagus tops each white ceramic plate, the glaze of which is cracking into hundreds of small light gray fractures. The hands of a single diner rest on top of the table. His right hand clutches at his napkin as his left grabs the index finger of his companion and pulls it back across the table. Disturbingly, it is stuffed like a sausage and tied to string. Nine more fingers are stuffed like this, tied up in a bow at the end of a string and staged like another component of the place settings for the table. The Dinner Companion illustrates the dissonant moment when a frantic desire for stability is met by a deranged act of self-deception set in motion to cope with those very needs.

In The Belt that Came in from the Night, a low vantage point, similar to camera angles used to build suspense in horror films, frames two socked feet standing before the threshold of a doorway. The hand of the apparently stooping figure gingerly holds up a belt that has curiously slipped through the crack beneath the door. A window set into the door reveals a darkened back yard where a headless figure can be seen slumped in the grass, leaning against a tall fence. For Herschlein, a belt’s ominous associations with misuse and abuse embody the ways in which banal household objects can take on meaning outside of their intended functions. Rather than inherent to the object, these connotations are the result of an object’s proximity to our emotional lives and our own potential to cause and receive harm. Or, as the artist puts it: “this is a regular haunting and we are the ghosts.”

As a part of a larger installation also titled Dweller, the exterior facade of a house stands in the center of a dark room. It is clad in thin black siding, and through two central windows a bed with rumpled blankets is visible against the far wall. From beneath the rumpled pillow on the narrow bed lay two hands—one gripping tightly to the sheets, the other offering a small handful of soil with a worm extending from its center. The wall that faces the bed is an expanse of painted light that accentuates the grain of the wooden wainscotting and the fleshy pink texture of the wall above it. A thin crack crawls up from the corner of one of the windows, disappearing behind a dark and heavy crown moulding. It is both a small gothic flourish and the seam at which the sculpture breaks down. Through small cracks like these, Herschlein attempts to deconstruct the work of make-believe using its own devices.

By recognizing these deceptions and seeing them for what they are, Herschlein hopes that a transformation of values becomes possible. Faced with an obviously constructed version of the self that is no longer animated by shame, guilt, or anger, the judgments felt to be inherent to the body may start to fall away. It is through these figures of the scarecrow, the puppet, and the doll that Herschlein hopes to find and cultivate a sense of agency and compassion.

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, fishing line

51.5 x 41.5 x 8 in

131 x 105.5 x 20.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, fishing line

51.5 x 41.5 x 8 in

131 x 105.5 x 20.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, fishing line

51.5 x 41.5 x 8 in

131 x 105.5 x 20.5 cm

aluminum, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, buckle

5 x 29.5 x 6.5 in

12.5 x 75 x 16.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string

41.5 x 47.5 x 8 in

105.5 x 120.5 x 20.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string

41.5 x 47.5 x 8 in

105.5 x 120.5 x 20.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string

41.5 x 47.5 x 8 in

105.5 x 120.5 x 20.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil

61.5 x 46.5 x 6.5 in

156 x 118 x 16 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil

61.5 x 46.5 x 6.5 in

156 x 118 x 16 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil

61.5 x 46.5 x 6.5 in

156 x 118 x 16 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, belt buckle

25.5 x 51 x 10 in

65 x 129.5 x 25.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, belt buckle

25.5 x 51 x 10 in

65 x 129.5 x 25.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, belt buckle

25.5 x 51 x 10 in

65 x 129.5 x 25.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, belt buckle

25.5 x 51 x 10 in

65 x 129.5 x 25.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string, fishing line

37.5 x 27.5 x 7.5 in

94.5 x 69.5 x 19 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string, fishing line

37.5 x 27.5 x 7.5 in

94.5 x 69.5 x 19 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string, fishing line

37.5 x 27.5 x 7.5 in

94.5 x 69.5 x 19 cm

aluminum, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, buckle

5.5 x 22.5 x 6.5 in

14 x 57 x 16.5 cm

aluminum, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, buckle

2.5 x 32 x 5 in

6.5 x 81.5 x 12.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, soil

100 x 139 x 23.5 in

254 x 353 x 59.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, soil

100 x 139 x 23.5 in

254 x 353 x 59.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, soil

100 x 139 x 23.5 in

254 x 353 x 59.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, soil

100 x 139 x 23.5 in

254 x 353 x 59.5 cm

aluminum, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, buckle

4 x 16 x 10 in

10 x 40.5 x 25.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string, soil

72.5 x 33 x 8.5 in

184 x 84 x 21.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string, soil

72.5 x 33 x 8.5 in

184 x 84 x 21.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string, soil

72.5 x 33 x 8.5 in

184 x 84 x 21.5 cm

wood, plaster, pigmented joint compound, epoxy putty, milk paint, wax, graphite, color pencil, string, soil

72.5 x 33 x 8.5 in

184 x 84 x 21.5 cm