JTT is pleased to present Mrs. Evan Williams, Jamian Juliano-Villani’s third solo show with the gallery.

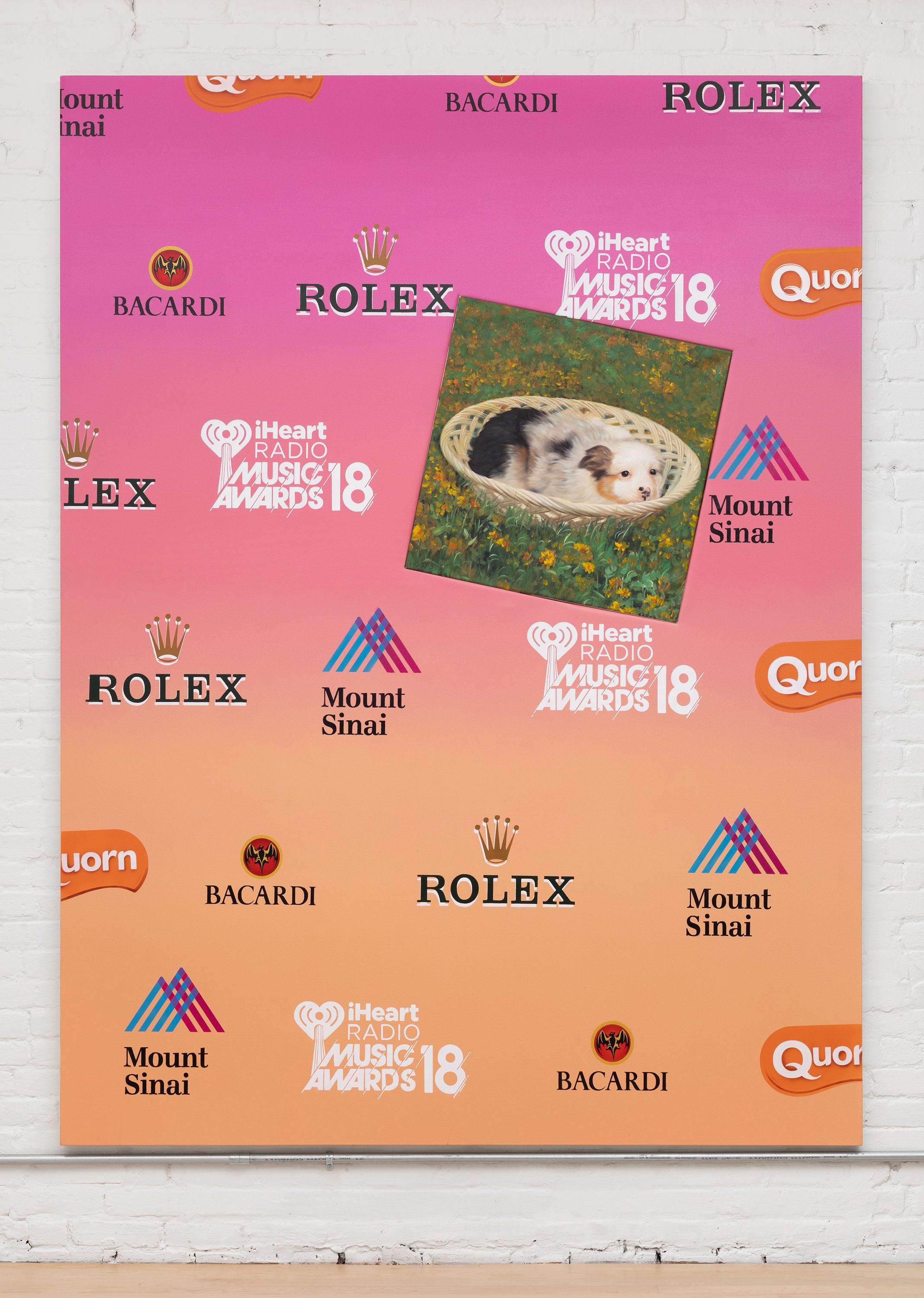

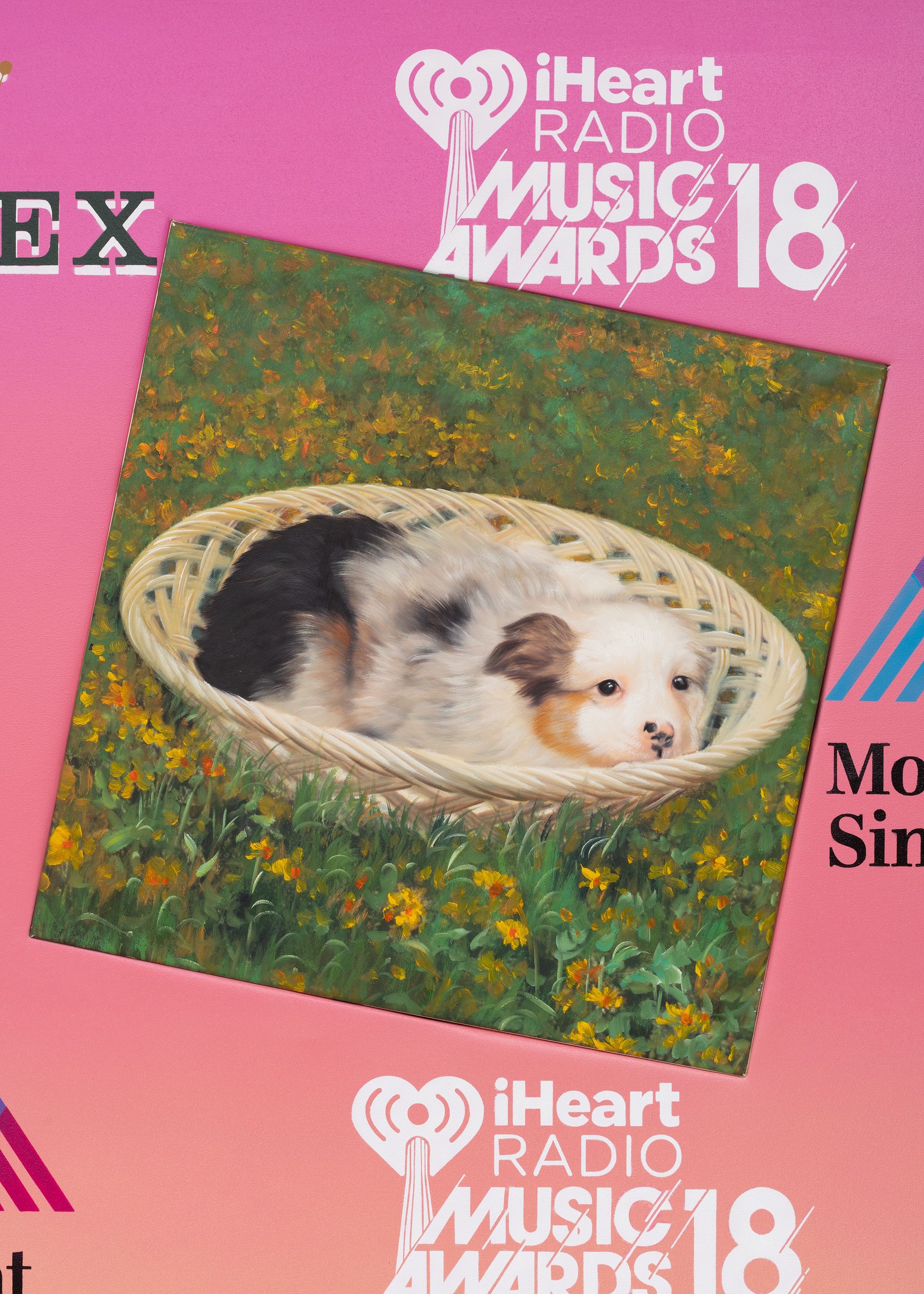

On view are 11 paintings, four of which feature sculptural interventions. Also included is a wall paper installation that gives the illusion of peering through the exhibition space to the office behind it. The unconventional juxtaposition of the “back room” plopped in the middle of the neutral white cube is a non-sequitur that reflects the artist’s continued use of this device within the individual works.

Chef Mike borrows its composition from Norman Rockwell’s 1942 painting of a Thanksgiving feast, Freedom from Want. In Rockwell’s original, a large turkey is being presented by a proud matriarch to a crowded table of eager guests across several generations. In Juliano-Villani’s Chef Mike, the idyllic meal is interrupted by a microwave which has been programmed to open its door every 10 seconds, ash multi-color LED lights, play, Stereo Love by the Romanian duo Edward Maya and Vika Jigulina and then close again. If Rockwell’s Freedom from Want is an iconic representation of cliché American values centered around a bounty and the wholesome tradition of sharing home-prepared food shared with loved ones; Juliano-Villani’s update offers the moment when that tradition ends.

Little Girls Stretching depicts two young twins who are stretching on a gym mat. While most of Juliano-Villani’s work can be considered to some degree through the lens of self-portraiture, Little Girls Stretching is explicitly so. Juliano-Villani herself is a twin and practiced gymnastics for most of her childhood, and went on to teach gymnastics in her teenage years and early twenties. While her work is often noted for the combination of disparate elements, Little Girls Stretching demonstrates a concision and continuity with regard to imagery and context that, in this case, changes the pace of the entire exhibition.

In The Origin of the World, Juliano-Villani makes an adolescent nod to the 1866 painting by Courbet that scandalized the French art-viewing elite. Hers features a tadpole-like creature with a human penis. Here, in a maneuver at once ambitious and self-deprecating, Juliano-Villani gestures to a quintessential example of art that pushes against the boundary of what is considered presentable, sophisticated, and worthy by presenting a seemingly sophomoric collage deployed to taboo-busting effect.

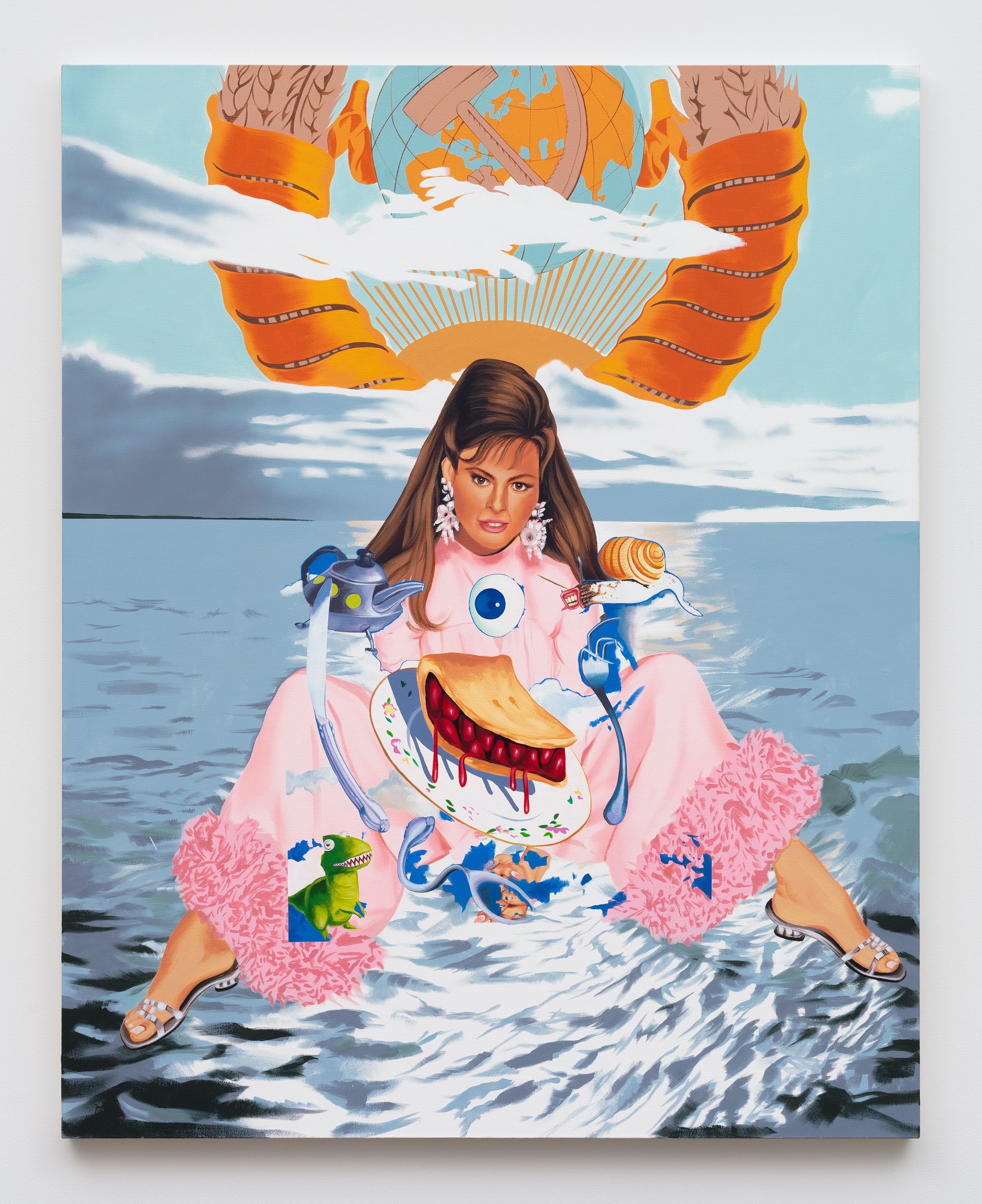

Give It To Someone Else features the American actress, singer and 1960s sex icon Raquel Welch. Welch was most well known for her role in the 1966 submarine science-fiction film Fantastic Voyage. As Welch rose to fame over the subsequent decade taking further roles of strong intelligent female characters, she helped dismantle Hollywood’s obsession with the ditzy blonde, showing America that witty brunettes can be sex icons too. Here Welch spreads her legs on the horizon over a glimmering ocean. In place of the sun is the State Emblem of the

Soviet Union which was adopted in 1923 and was used until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. This particular rendition of the emblem was taken from Erik Bulatov’s (b. 1933, Sverdlovsk, Russia) 1977 painting Brezhnev, the Soviet Space. Juliano-Villani came across Bulatov’s work frequently at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, where she received her undergraduate degree in 2013. The Zimmerli’s collection contains 22,000 Russian and Soviet nonconformist art objects, re ective of a movement that operated outside of the rubric of the highly politicized Social Realism, and ourished at a time where artists had more freedom to create non-sanctioned work without fearing repercussions. As Russian curator, author and museum director Joseph Bakstein wrote of the movement: “In the Soviet Union, art was doubly real precisely because it had no relation to reality. It was a higher reality.... The goal of nonconformism in art was to challenge the status of of cial artistic reality, to question it, to treat it with irony.”

The demonstration of unharnessed artistic expression left a strong impression on Juliano-Villani in her formative years. Throughout this exhibition, and across her collective body of work, is the implication that concern for sense, conclusion, and decorum can be shuf ed off in the service of an idiosyncratic expression of uninhibited thought memory and impulse.

pencil sharpener, pencil, audio

7 x 4 x 7 in

18 x 10 x 18 cm

pencil sharpener, pencil, audio

7 x 4 x 7 in

18 x 10 x 18 cm

pencil sharpener, pencil, audio

7 x 4 x 7 in

18 x 10 x 18 cm

acrylic on canvas

50 x 74 in

127 x 188 cm

acrylic on canvas

86 x 128 in

218.5 x 325 cm

acrylic on canvas

86 x 128 in

218.5 x 325 cm

acrylic on canvas

86 x 128 in

218.5 x 325 cm

acrylic on canvas, microwave

90 x 70 in

228.5 x 178 cm

acrylic on canvas, microwave

90 x 70 in

228.5 x 178 cm

acrylic on canvas, microwave

90 x 70 in

228.5 x 178 cm

acrylic on canvas

65 x 80 in

165 x 203 cm

acrylic on canvas

65 x 80 in

165 x 203 cm

acrylic on canvas, step stool

94.5 x 70 x 28 in

240 x 178 x 70.5 cm

acrylic on canvas, step stool

94.5 x 70 x 28 in

240 x 178 x 70.5 cm

acrylic on canvas, step stool

94.5 x 70 x 28 in

240 x 178 x 70.5 cm

acrylic on canvas

24 x 18 in

61 x 45.5 cm

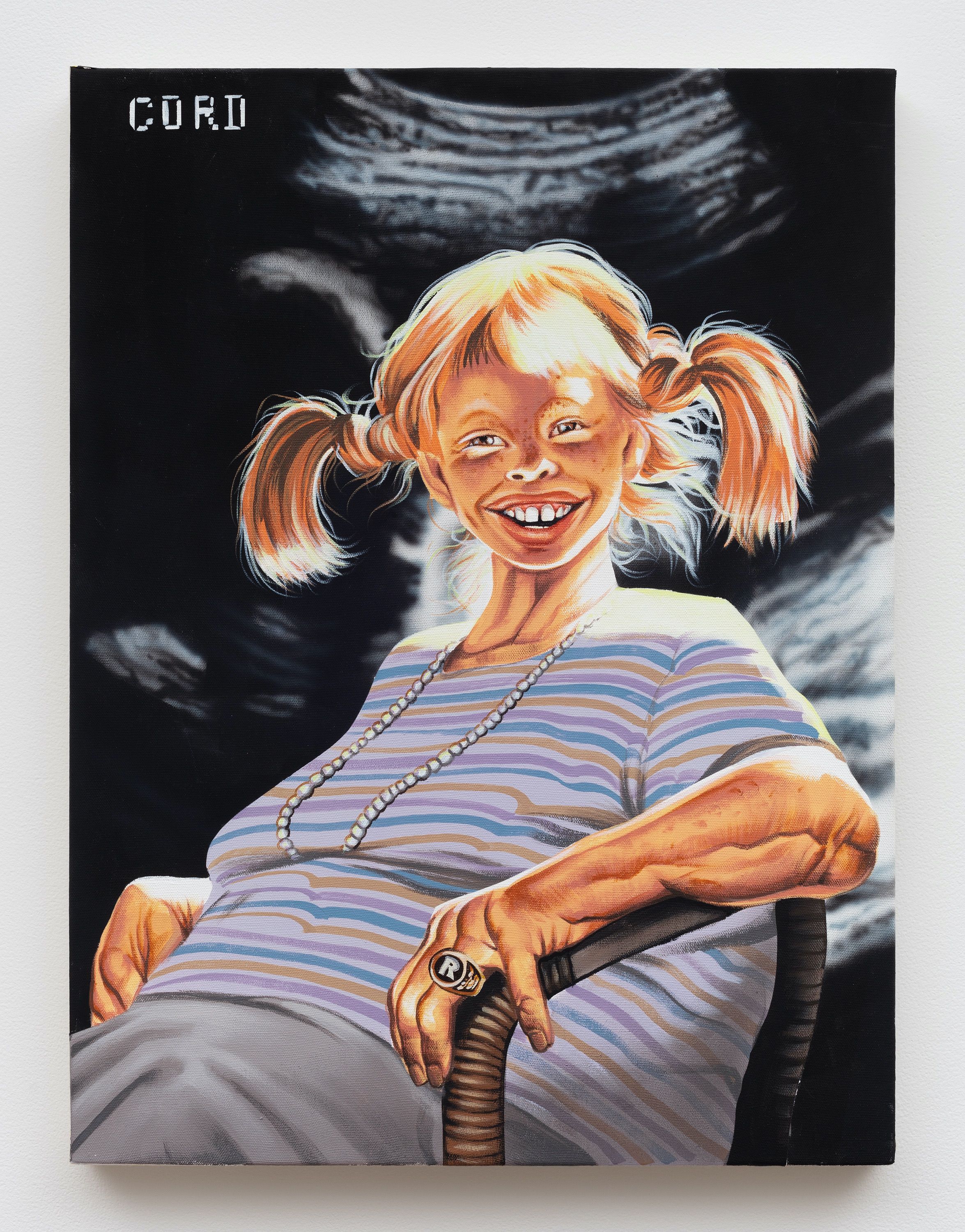

acrylic on canvas

60 x 48 in

152.5 x 122 cm

acrylic on canvas

60 x 48 in

152.5 x 122 cm

acrylic on canvas, electric sign

90 x 70 x 6 in

228.5 x 178 x 15 cm

acrylic on canvas, electric sign

90 x 70 x 6 in

228.5 x 178 x 15 cm

acrylic on canvas

48 x 40 in

122 x 101.5 cm

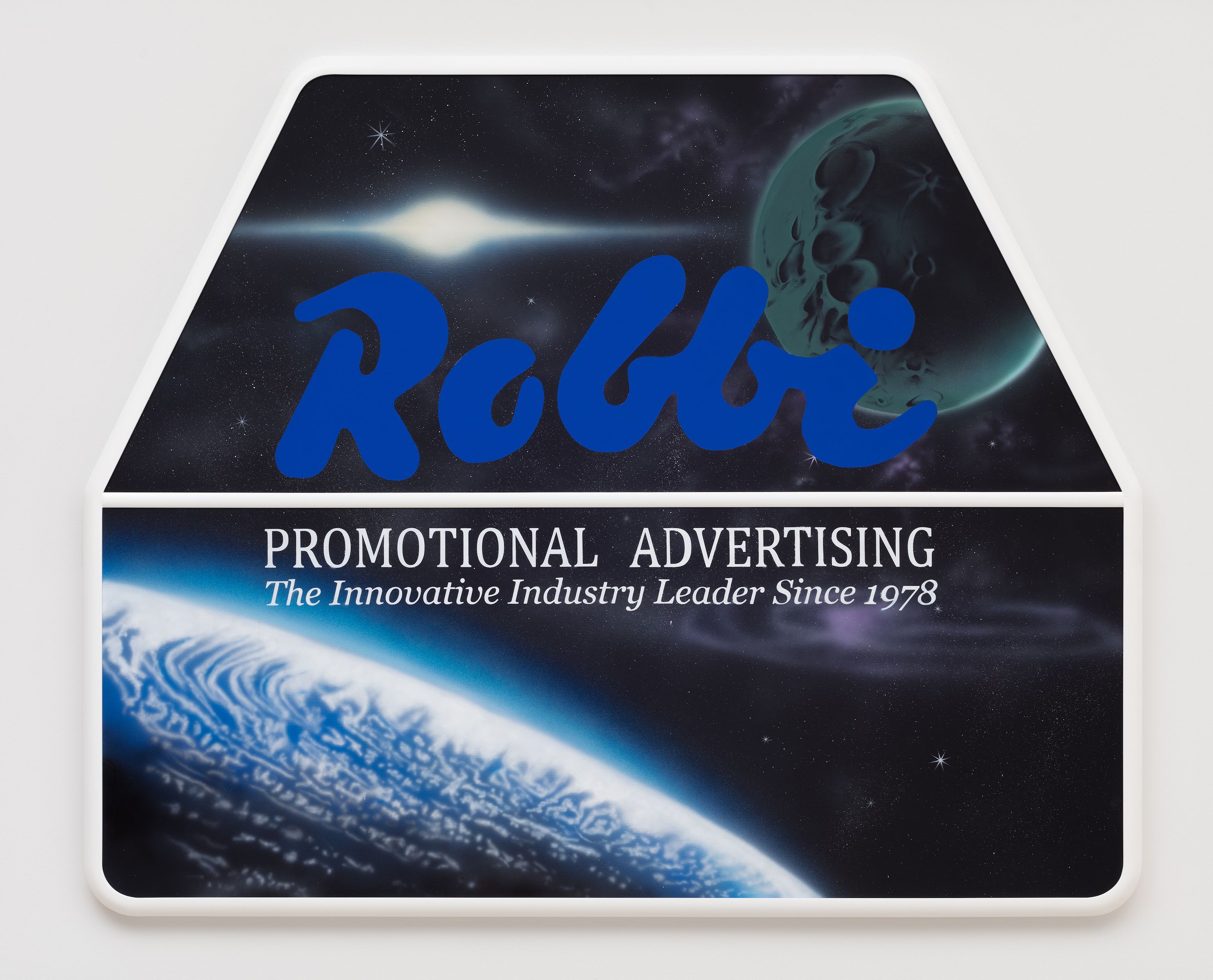

acrylic on canvas

88 x 58 x 9 in

223.5 x 147.5 x 23 cm

acrylic on canvas

88 x 58 x 9 in

223.5 x 147.5 x 23 cm

acrylic on canvas

88 x 58 x 9 in

223.5 x 147.5 x 23 cm

oil on canvas

21 x 70 in

53.5 x 178 cm

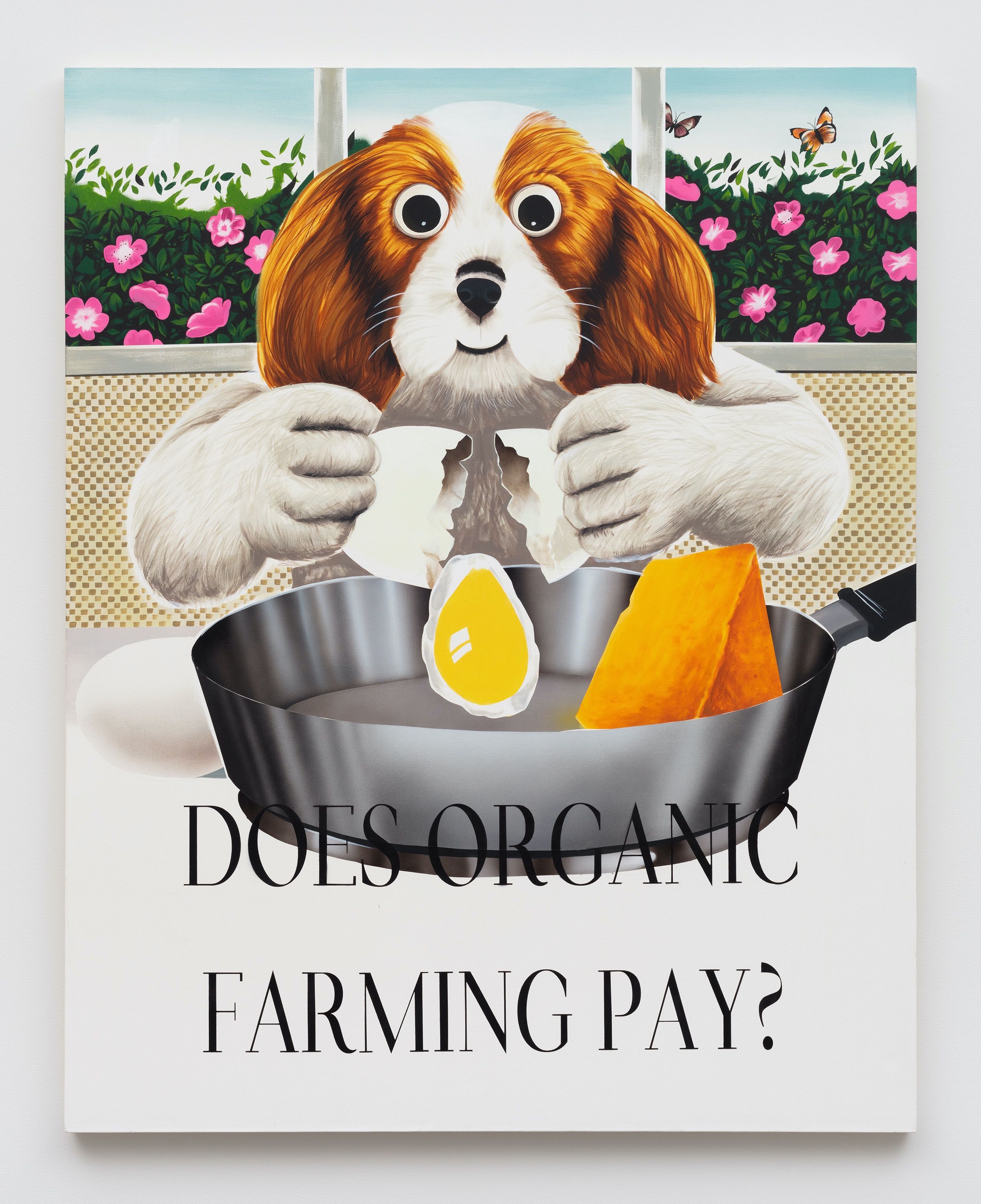

acrylic on canvas

96 x 72 in

244 x 183 cm

acrylic on canvas

96 x 72 in

244 x 183 cm

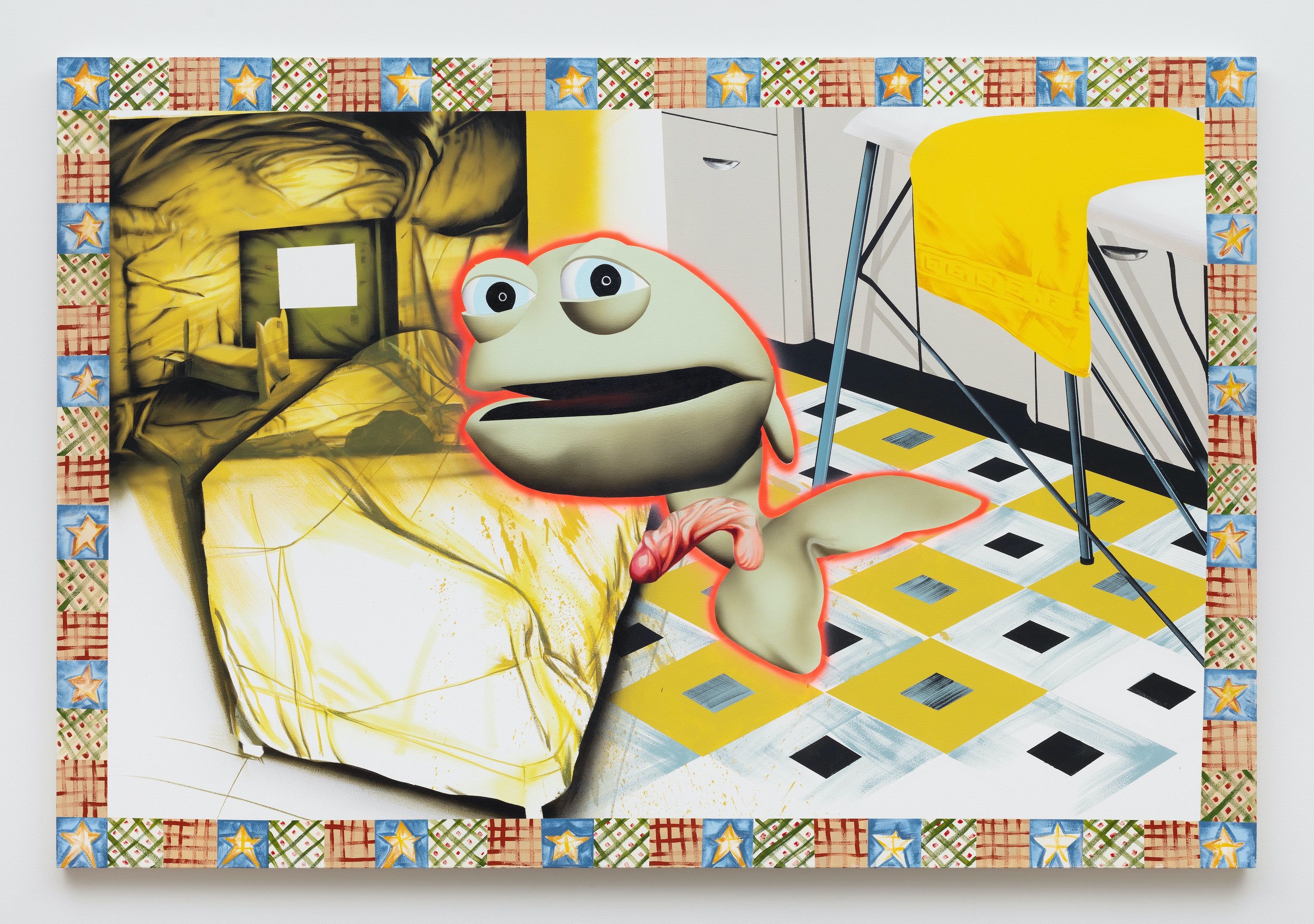

acrylic on canvas, faux finish frame

50 x 66.5 x 5 in

127 x 168.5 x 12.5 cm

acrylic on canvas, faux finish frame

50 x 66.5 x 5 in

127 x 168.5 x 12.5 cm