This exhibition brings together artists working across disciplines and generations—Anna-Sophie Berger, Anthea Hamilton, Maren Hassinger, Charles LeDray, Pat Oleszko and William Teason—whose work draws on the everyday things that make up our surroundings. As conveyors of meaning and action, objects tend to play an outsized role in our lives. Whether by repurposing common things, removing them from their functional orbits, exploring their absurdity and gravity, or pushing them to their cognitive limits, these artists reveal a myriad of ways that objects can serve to embody their beholders. As sociologist Bruno Latour has suggested, “things do not exist without being full of people.”

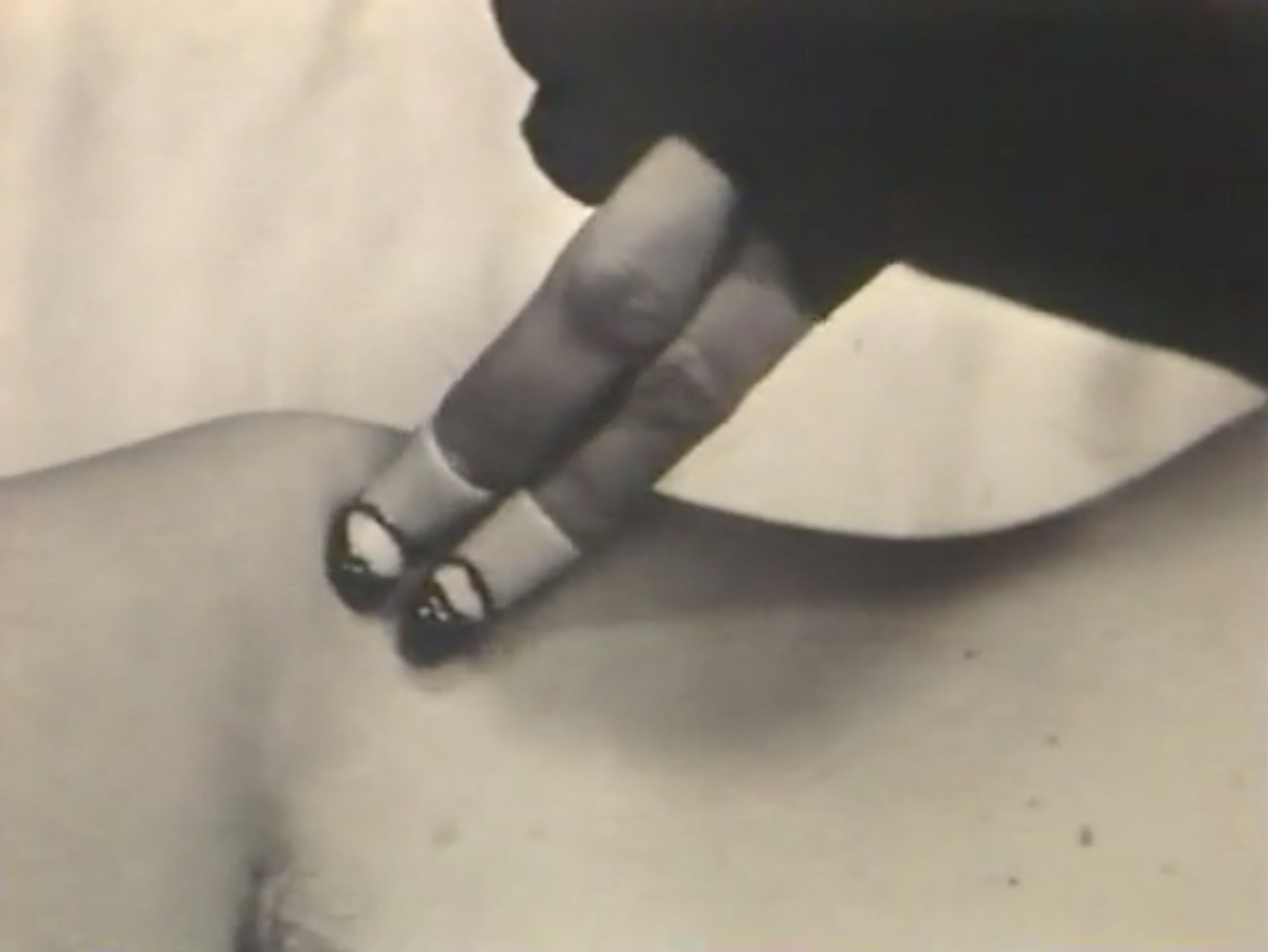

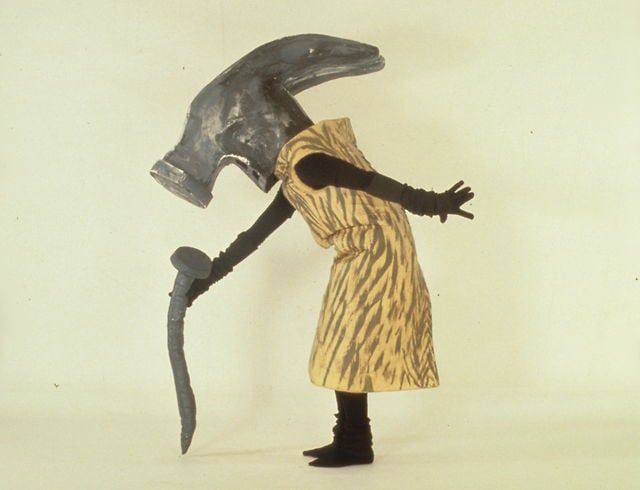

Several works on view demonstrate this through literal embodiment. Pat Oleszko’s costumes transform their wearer into absurd entities; in this case, an anthropomorphized household tool and cluster of inflated breasts. Throughout her career, Oleszko has used satire and theatre to revolt against a male-dominated society and respond to urgent issues. These costumes correspond to Mike Hammer and Udder Delight, two characters imagined by Oleszko in the 1980s as part of her experimental performances and videos, which she has been writing, directing, performing, and creating elaborate sets and costumes for for over four decades. Three videos on view from this period reveal her dynamic productions in action. Often taking on the role of the jester, Oleszko considers the artist’s position as someone who, in her words, can “speak the truth—and get away with it.”

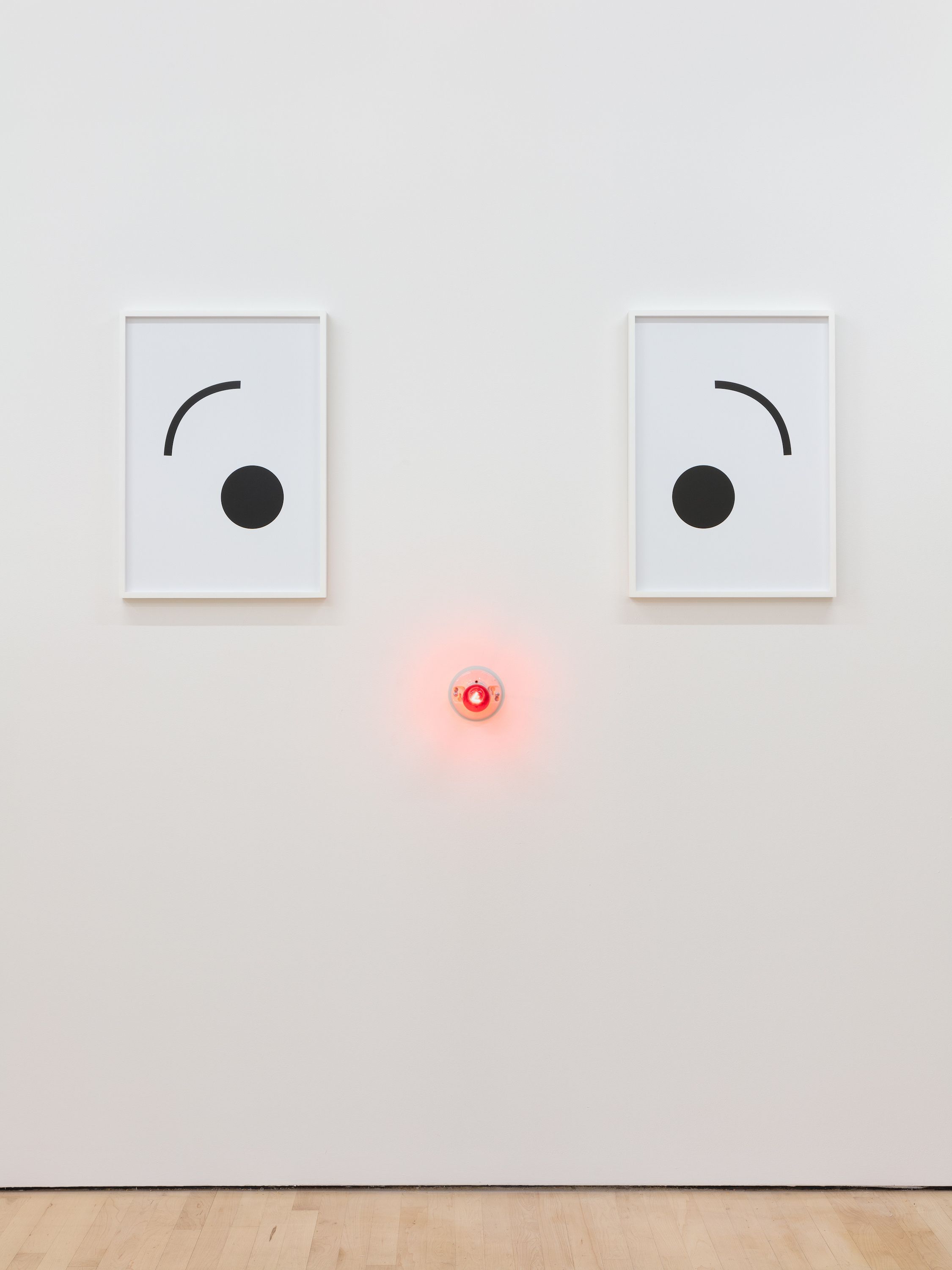

The jester makes a physical appearance here as an outlined figure in the work of Anna-Sophie Berger. In lunch, a transparent green and white sheath in the shape of a body with the jester’s familiar three-pointed hat houses cans of peas and beans. In this case, the figure has exhausted itself, its only support packaged foodstuffs stacked and toppled. In other works on view, Berger exploits our inclination to perceive faces in everyday things by placing two preexisting works in dialogue: her glyphic McCarren Diptych is shown together with Hirn (Brain), red light bulbs indicative of illicit activity. Throughout her practice, Berger is particularly attentive to our physical relationships to utilitarian objects in order to reveal what their use and exchange says about human relationships.

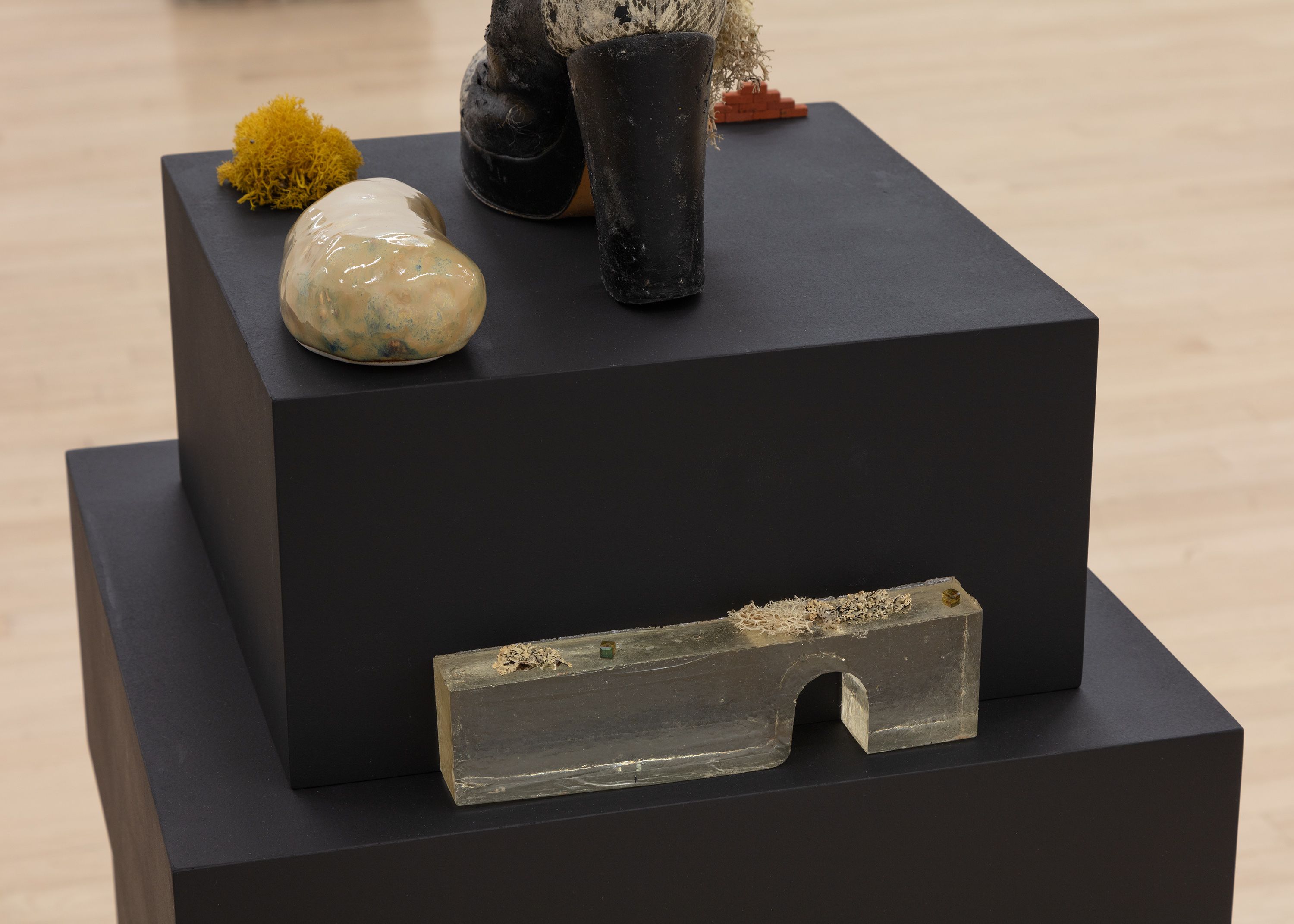

Through scale shifts and assemblage, Anthea Hamilton’s two sculptures fuse organic and human-made objects to draw a parallel between cultural and natural phenomena. In Papilio Whip Butterfly, the creature’s enormous size and material components like luxury fabrics and leather whips establish a curious magnetism. In Natural Livin’ Boot, a readily identifiable object associated with fashion meets the unexpected forms and spectacles of the natural world. In the way that objects undergo a transformation when they move between cultures, eras, and geographical space, Hamilton’s works suggest a physical transformation of their own.

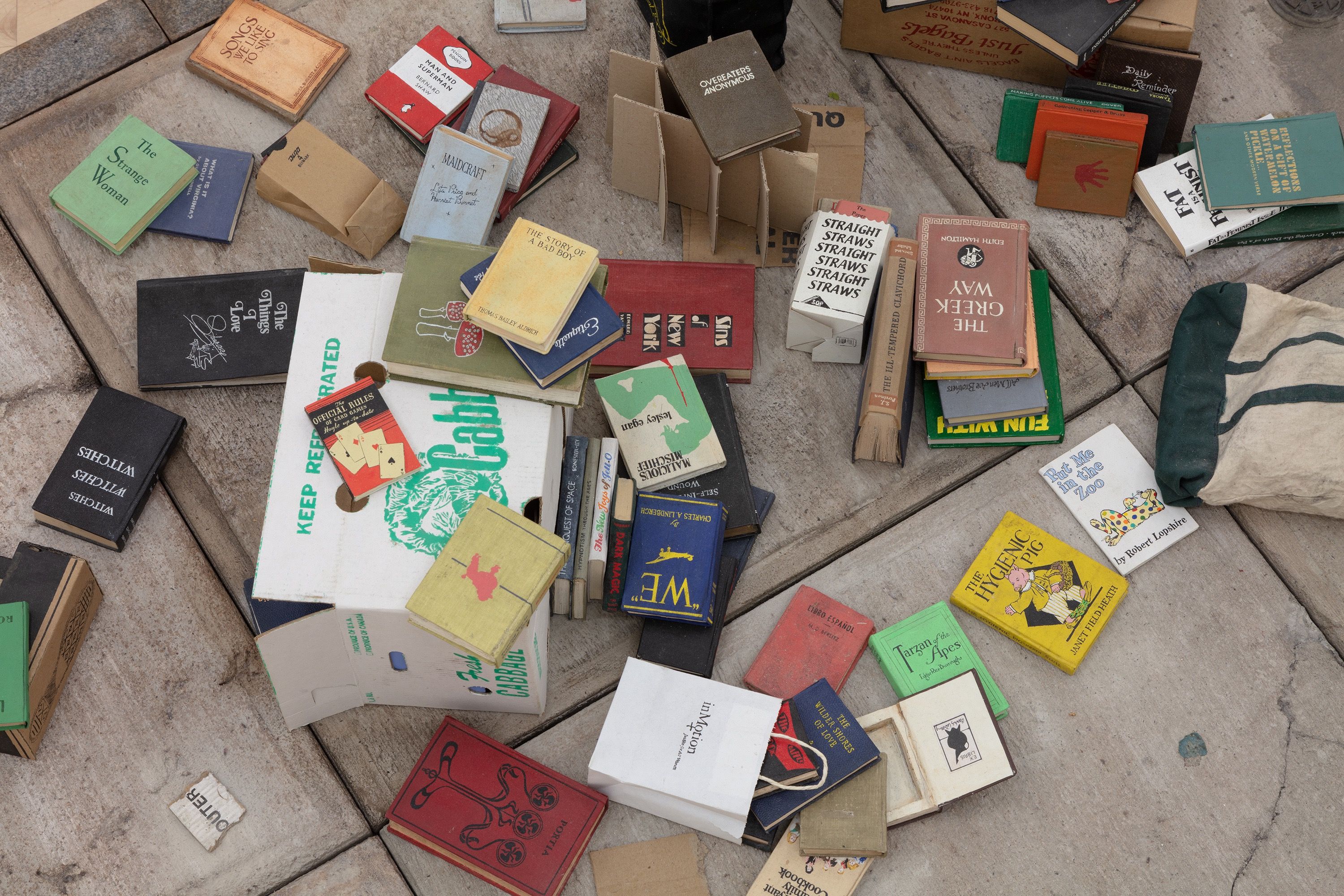

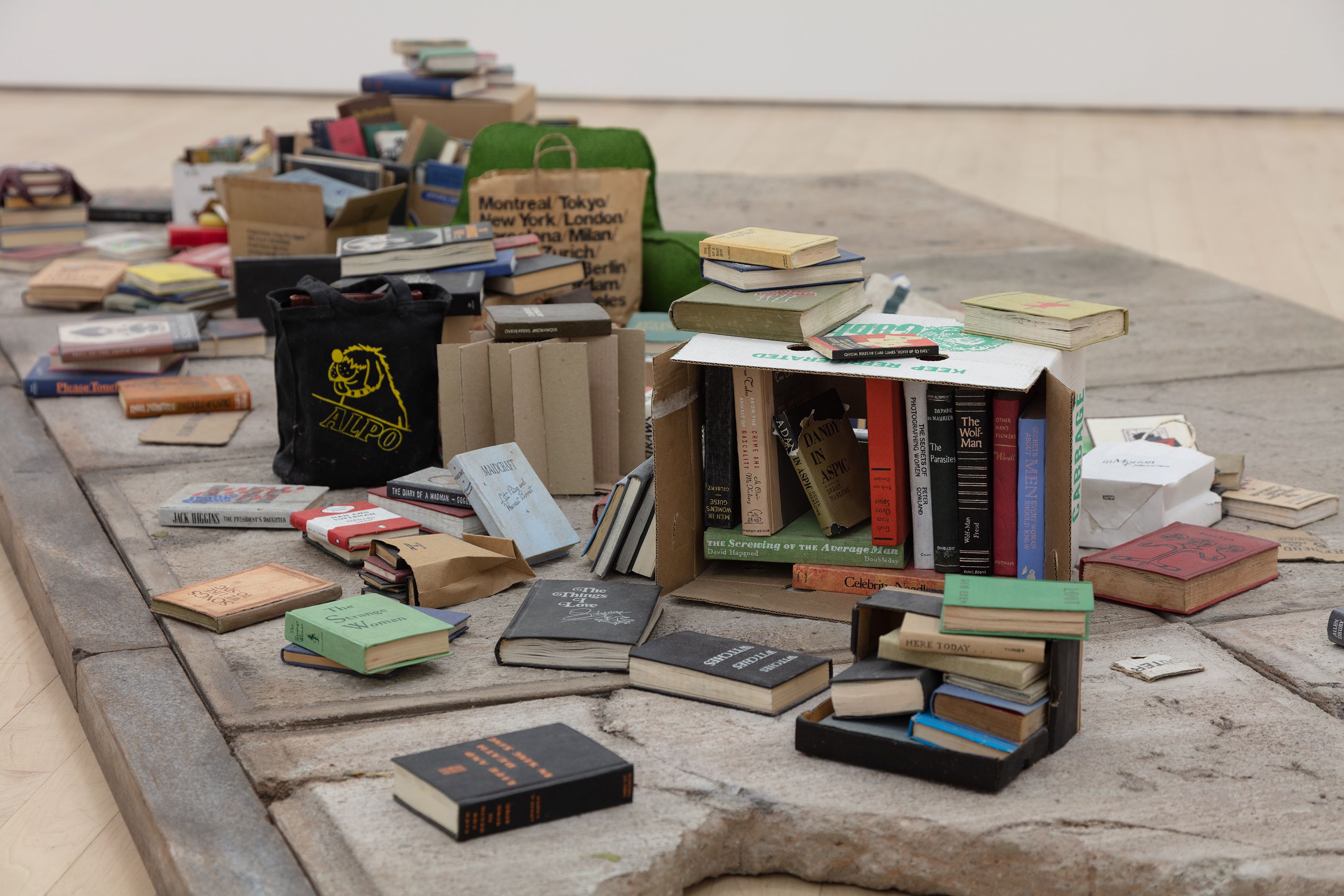

Our personal relationships to objects is central to the work of Charles LeDray, whose sculptures of common household items are meticulously replicated on a miniature scale. In Free Public Library discarded books spill from boxes and tote bags, littering a city sidewalk for the perusal of passers-by. Collectively, the titles begin to reveal a story of their own. The scale shift invokes a dizzying awareness of our presence before these objects: they are in our physical proximity, and yet, inaccessible. This effect is further intensified by LeDray’s convincing fabrication of weathering and wear.

Discarded and disposable objects feature prominently in the works on view by Maren Hassinger. In her installation from 1982 titled Pink Trash (restaged in Prospect Park in 2017), Hassinger ventured to three New York City parks and swapped the garbage on site with pink trash she had painted and collected. Contrasting with the green grass and taking on the appearance of fallen leaves, the scattered objects called attention to the use of natural public space through artifacts of human activity, drawing a parallel between natural and human-made detritus. A similar repurposing of found objects is evident in Hassinger’s Sit Upons, seat cushions woven from issues of the New York Times. Hassinger recalls weaving sit upons with peers during her time spent as a Camp Fire Girl, the first non-religious, multicultural organization for girls. To recreate them, Hassinger engaged the same collaborative process, drawing on women’s work, and collective, craft-based practices.

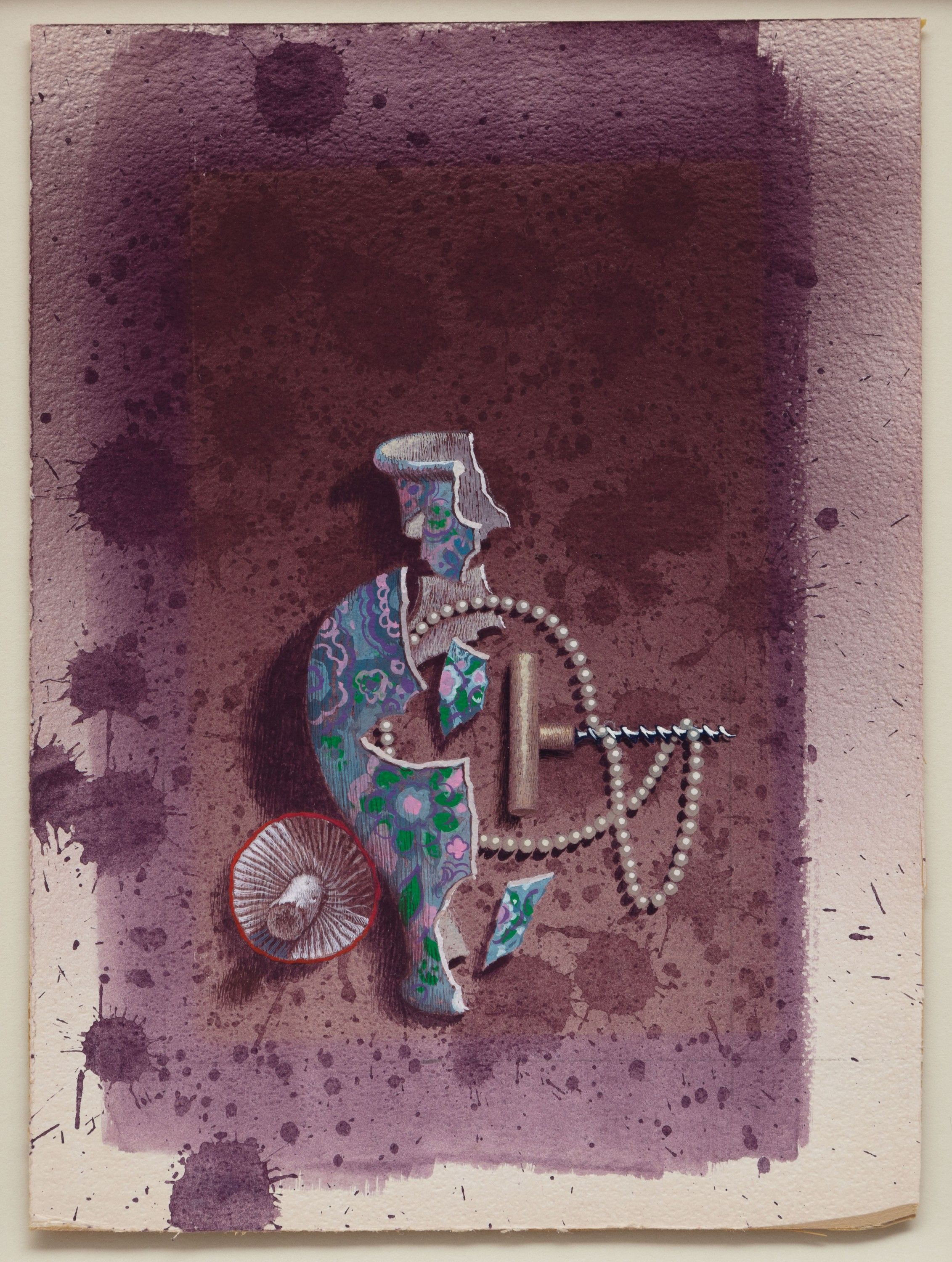

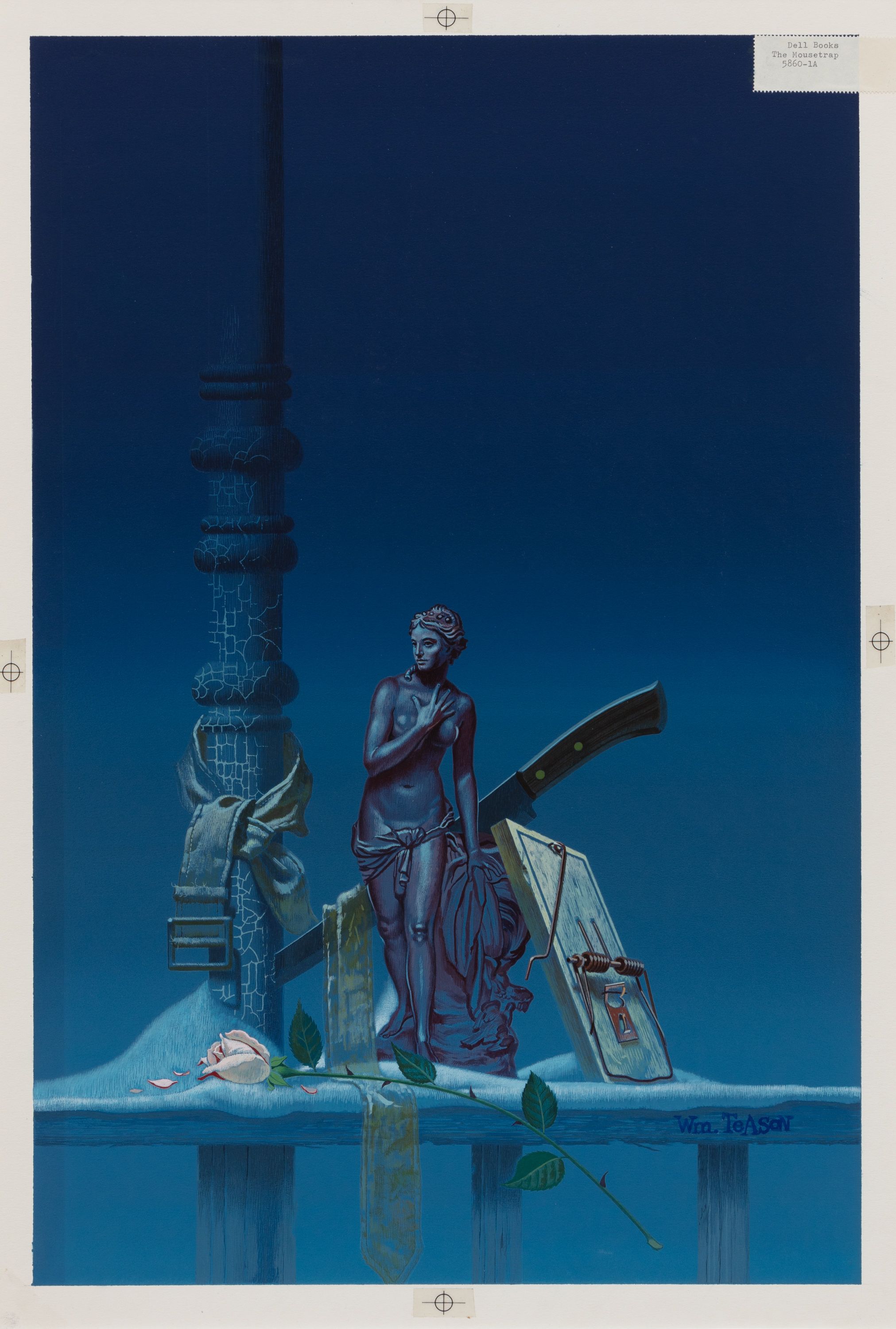

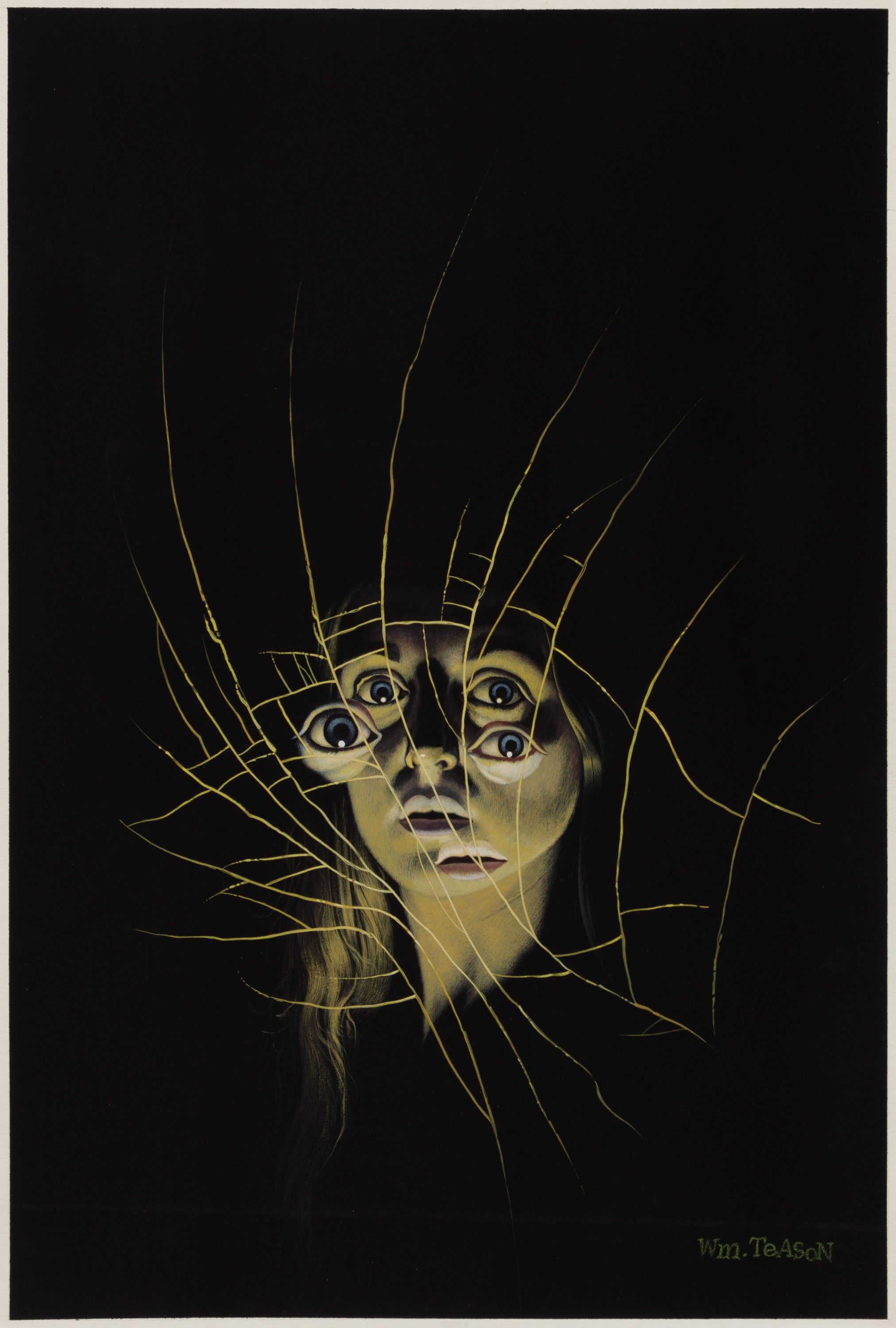

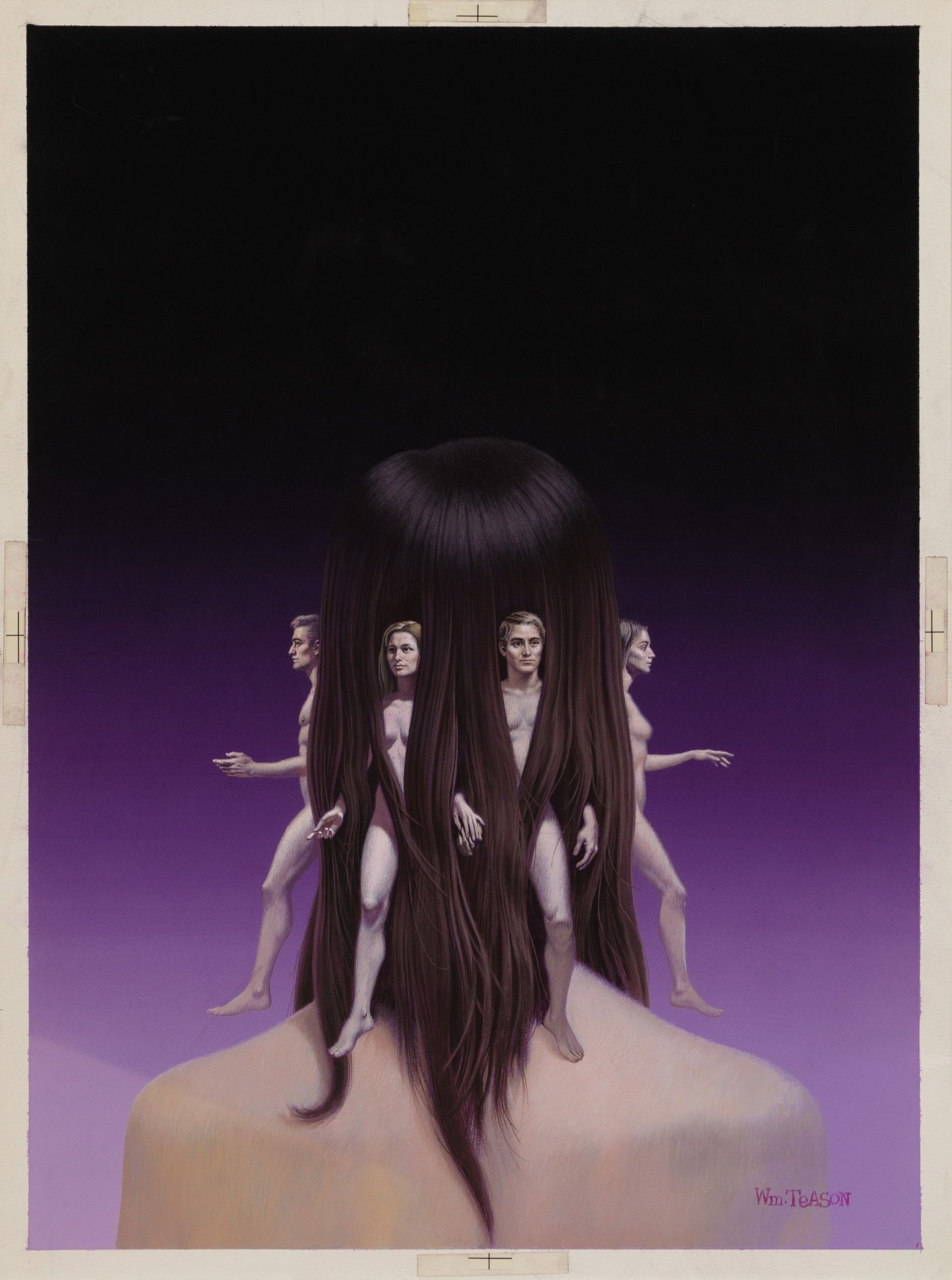

Detailed renderings of still lives assemble strange panoplies of objects in the works of William Teason. Teason was a lifelong illustrator and painter, best known for his covers for paperback editions of popular mystery books by authors such as Agatha Christie and Shirley Jackson, as well as editions of the Sherlock Holmes series and many others. To prepare his cover illustrations, Teason would read each novel in its entirety, noting particular objects that played a significant role in the plot’s direction. He would then paint small scale “comps,” or compositions in order to experiment with different arrangements of these objects in a process of communication with his editors. The resulting gouaches have an enigmatic symbolism all their own. By composing only objects that feature prominently in the novel’s plot into iconographic compositions, Teason manages to imbue his paintings with a standalone aura of both suspicion and dread.

Natural Livin' Boot, 2015

mixed media

56.5 x 16 x 16 in

143.5 x 40 x 40 cm

Natural Livin' Boot, 2015 (detail)

mixed media

56.5 x 16 x 16 in

143.5 x 40 x 40 cm

Kitchenette, 2011-2014

acrylic on particle board, copper, sewn fabrics, and wire

19.5 x 13.5 x 2.5 in

49 x 34.5 x 6.5 cm

Kitchenette, 2011-2014

acrylic on particle board, copper, sewn fabrics, and wire

19.5 x 13.5 x 2.5 in

49 x 34.5 x 6.5 cm

Udder Delight (from the performance Bluebeard's Hassle: The Writhes of the Wives), 1989

nylon, blower

82 x 48 x 74 in

208.5 x 122 x 188 cm

Udder Delight (from the performance Bluebeard's Hassle: The Writhes of the Wives), 1989 (detail)

nylon, blower

82 x 48 x 74 in

208.5 x 122 x 188 cm

Untitled (Composition for 'Partners in Crime'), 1963

gouache on illustration board

9 x 6.5 in

23 x 16.5 cm

Papilio whip butterfly, 2018

printed fabric, Devoré velvet, Ikat cotton, upholstery foam, leather whips, metal cable ties

90.5 x 82.5 x 10.5 in

230 x 210 x 27 cm

Papilio whip butterfly, 2018

printed fabric, Devoré velvet, Ikat cotton, upholstery foam, leather whips, metal cable ties

90.5 x 82.5 x 10.5 in

230 x 210 x 27 cm

Papilio whip butterfly, 2018 (detail)

printed fabric, Devoré velvet, Ikat cotton, upholstery foam, leather whips, metal cable ties

90.5 x 82.5 x 10.5 in

230 x 210 x 27 cm

Mike Hammer (from The Tool Jest), 1984

foam, fabric, paint, wire

76 x 22 x 42 in

193 x 56 x 106.5 cm

lunch, 2017

polyester, thread, cans

dimensions variable

Sit Upons, 2010

New York Times newspapers

15.5 x 15.5 x 1.5 in each, 11 in tall total

39.5 x 39.5 x 4 cm each, 28 cm tall total

(45 pieces per unit, 8 units total)

Pink Trash, 1982

three chromogenic color photographs

9 x 13.5 in, each

23 x 34.5 cm, each

Footsi, 1979 (still)

video

with David Robinson

4:50 minutes

The Clown Jewells, 1981 (still)

video

with David Robinson

8:09 minutes

Handyman's Tool Jest, 1984 (still)

video

with David Robinson

5:24 minutes

Sit Upons, 2010

New York Times newspapers

15.5 x 15.5 x 1.5 in each, 11 in tall total

39.5 x 39.5 x 4 cm each, 28 cm tall total

(45 pieces per unit, 8 units total)

left and right:

McCarren Diptych, 2020

inkjet print on paper

24 x 34 in (24 x 17 in, each)

61 x 86.5 cm (61 x 43 cm, each)

center:

Hirn (Brain), 2020

red lightbulb, ceramic socket

dimensions variable

The Mousetrap, 1968

gouache on paper

28 x 21.5 in

71 x 54.5 cm

Elizabeth, 1976

gouache on illustration board

21.5 x 14.5 in

54 x 37 cm

Free Public Library, 2015-2019

paper, cardboard, fabric, thread, acrylic paint, ink, acrylic varnish, acrylic gel medium, brass, patina, bubble gum, glass, metal, wire, wood, cement board, cement, granite, glue, fiberfill, and Mylar

10 x 97 x 50.5 in

25.5 x 246.5 x 127.5 cm

Free Public Library, 2015-2019

paper, cardboard, fabric, thread, acrylic paint, ink, acrylic varnish, acrylic gel medium, brass, patina, bubble gum, glass, metal, wire, wood, cement board, cement, granite, glue, fiberfill, and Mylar

10 x 97 x 50.5 in

25.5 x 246.5 x 127.5 cm

Free Public Library, 2015-2019 (detail)

paper, cardboard, fabric, thread, acrylic paint, ink, acrylic varnish, acrylic gel medium, brass, patina, bubble gum, glass, metal, wire, wood, cement board, cement, granite, glue, fiberfill, and Mylar

10 x 97 x 50.5 in

25.5 x 246.5 x 127.5 cm

Free Public Library, 2015-2019 (detail)

paper, cardboard, fabric, thread, acrylic paint, ink, acrylic varnish, acrylic gel medium, brass, patina, bubble gum, glass, metal, wire, wood, cement board, cement, granite, glue, fiberfill, and Mylar

10 x 97 x 50.5 in

25.5 x 246.5 x 127.5 cm

Free Public Library, 2015-2019 (detail)

paper, cardboard, fabric, thread, acrylic paint, ink, acrylic varnish, acrylic gel medium, brass, patina, bubble gum, glass, metal, wire, wood, cement board, cement, granite, glue, fiberfill, and Mylar

10 x 97 x 50.5 in

25.5 x 246.5 x 127.5 cm

An Overdose of Death, 1972

gouache on illustration board

21.5 x 14.5 in

54.5 x 37 cm

Untitled (Occult), n.d.

gouache on illustration board

22 x 16.5 in

56 x 42 cm

A Study in Scarlet and the Sign of Four, 1963

gouache on illustration board

18.5 x 13 in

47 x 32.5 cm

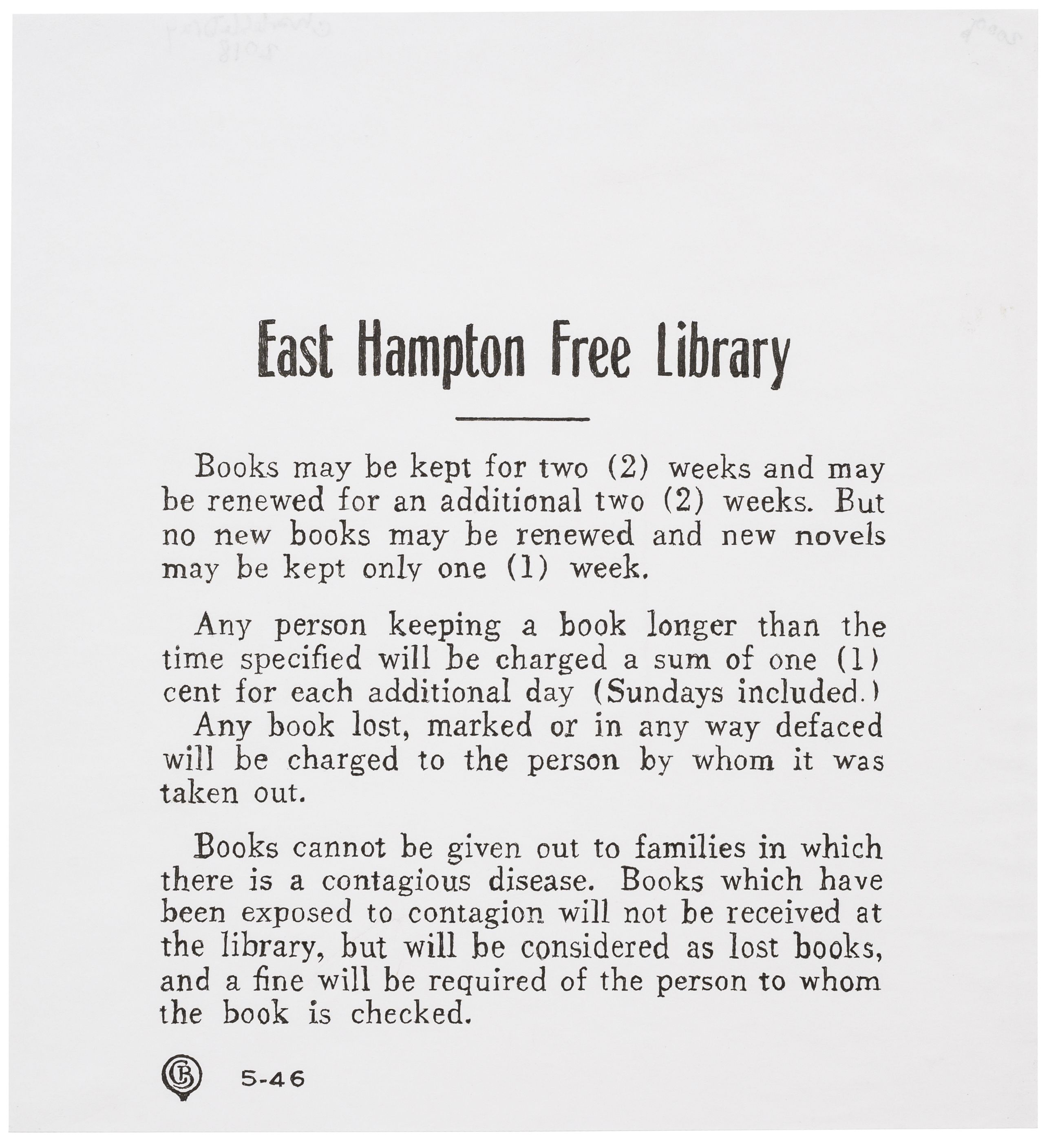

East Hampton Free Library (Rules), 2018

india ink on paper

7.5 x 7 in

19.5 x 18 cm