On November 13, 2010, I took a bus to Philadelphia for a tour of Fleisher Ollman’s Four Decades exhibition, a show organized on the occasion of John Ollman’s 40th anniversary at the gallery. A dear friend Jonathan Berger, who has a gift for acknowledging true visionaries, suggested I meet John. When I found out that he would be giving a tour of the exhibition I thought it would be a non-intrusive way to introduce myself to him.

At the time I was working as a director of Kimmerich Gallery in Tribeca, but I didn’t have much of a vision for my future outside of knowing that galleries were a special, weird, and autonomous corner of the world that I worked well in. I was in a dreamy and uncertain time in my life where I thought I might work as a director of a gallery forever, or maybe become a curator (a role that requires a type of rigorous academic memory I lack and would have been horrible at), or maybe pursue a career as an artist, or maybe one day I would do the impossible and open a gallery. In either of these roles, John was an inspiration and a logical mentor for me to pursue.

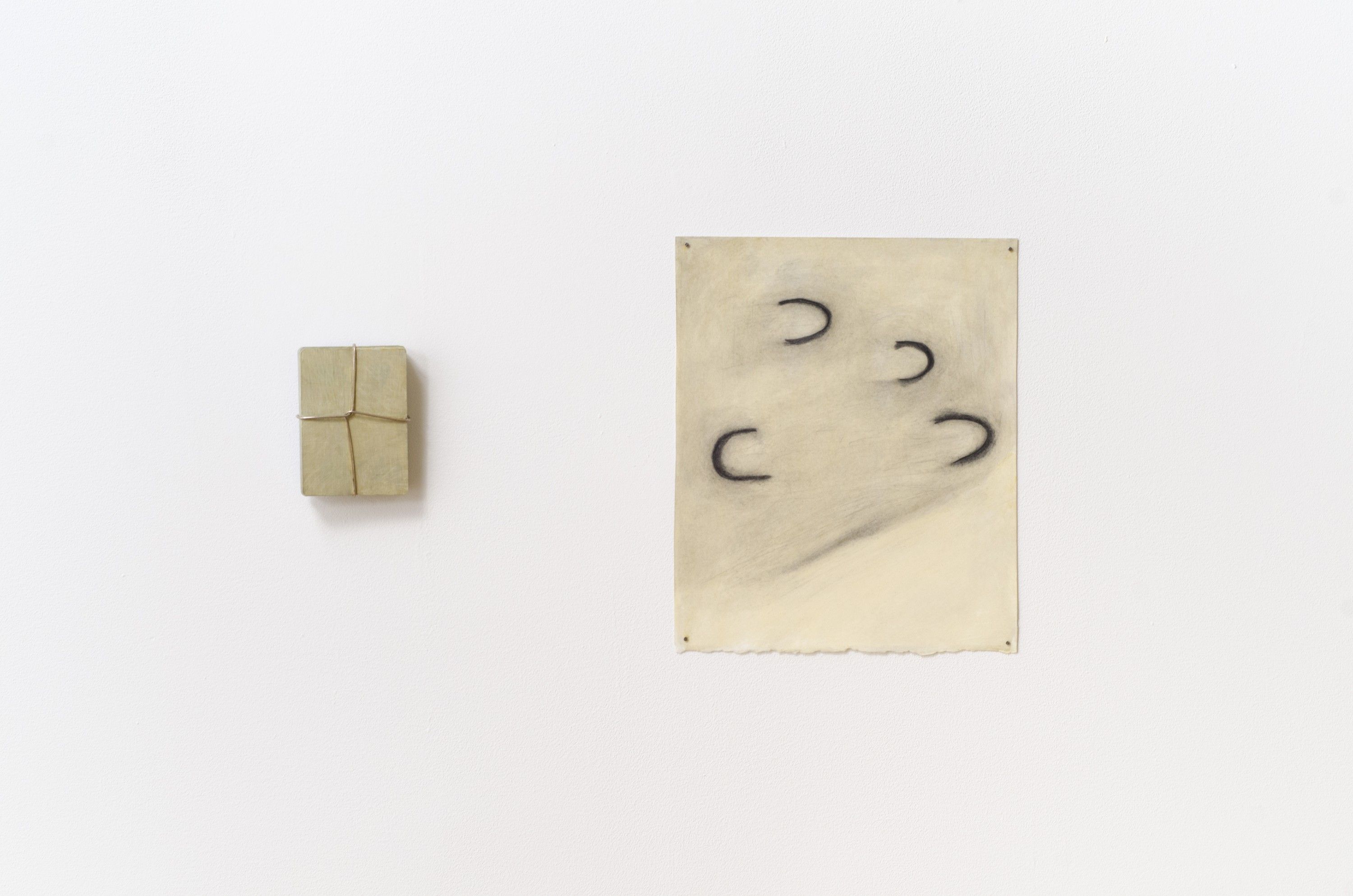

The gallery was on a second floor space on Walnut Street with dark concrete floors and dramatic spot lighting. When John started the tour he dove right into the art objects and the artists that made them, not stopping to digress on himself or engage in gratuitous pleasantries with visitors. The artist list for Four Decades included 36 artists, many of which are incredibly important to me now, but at the time I only knew three: Joseph Cornell, Forest Bess, and Charles Burchfield. That day, as John walked an attentive group of visitors through the past 40 years of his life, I learned who Bill Walton, Ray Yoshida, Joseph Yoakum, Philadelphia Wireman, P.M Wentworth, Bill Traylor, Tramp Art, Edgar Tolson, Martín Ramirez, Christina Ramberg, Horace Pippin, Jim Nutt, Frank Jones, Jess, Morris Hirshfield, William Hawkins, Howard Finster, William Edmondson, Felipe Jesus Consalvos and James Castle were. Object by object, John entirely disturbed my understanding of art made in America during the 20th century and unveiled the many histories that I didn’t know. I saw a Christina Ramberg for the first time, and I don’t mean for the first time in person, I mean for the first time ever. John has that old school dealer way of teaching history through delicate and overlooked objects themselves. The most memorable work for me was a small wall bound Bill Walton titled, West Main 131, n.d. made of a block of wood with a few pieces of lead wedged into a small split. Its surface was rubbed carefully with a brass leaf, gently confusing the wood’s materiality. I would learn that day that Bill Walton was a sculpture artist who made delicate post-minimal objects in the ‘80s, ‘90s and early 2000s, all of which are intentionally undated. Walton started as a printmaker and his obsession with the process of spreading ink thickly on a metal plate would launch him into a career of carefully altering the surfaces of objects. A year and a half later when I opened JTT, I would open with a solo show by Bill Walton curated over two spaces in collaboration with James Fuentes. John would generously consign me Bill Walton’s work for the show. But for that evening, West Main 131 stole my heart.

At the end of the tour, John showed his guests a small note that he wrote Janet Fleisher when he was 26 years old, applying for a job as director of her gallery, and I felt an ambitious if not superstitious connection between John and myself (November 13 is my birthday and I turned 26 that day). When looking back on my journey to owning a gallery, the connection I made between myself and John that day would be the single most inspirational event to allow me to take my dream of starting a gallery more seriously.

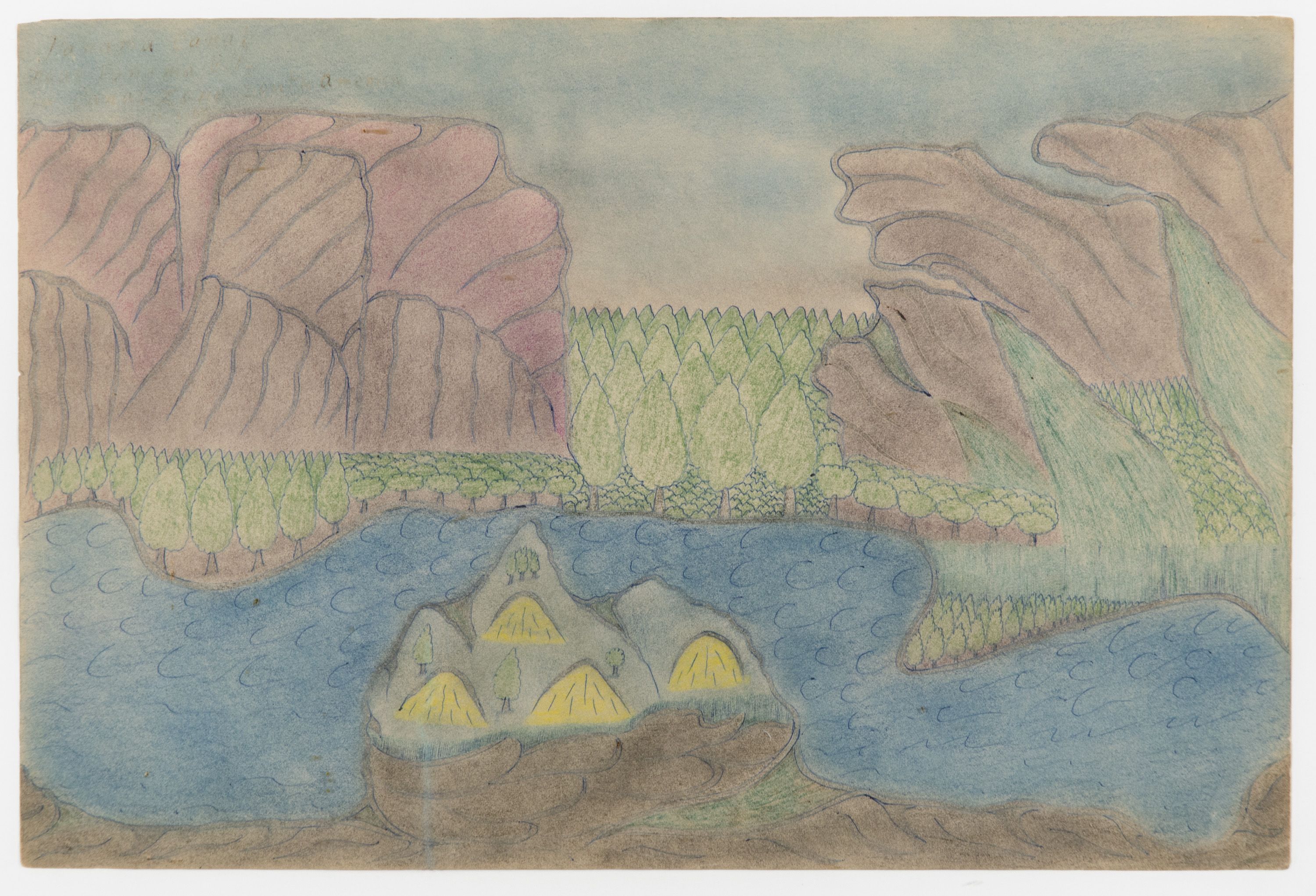

After the opening I attended what I would later learn is a traditional post-opening dinner at John’s home. The tables were covered with generous portions of sliced meats and cheeses that was uncommon to the New York openings I was attending at the time. In his living room Bill Traylors were carefully hung to avoid sunlight, and Howard Finsters lined the stairwell up to the second floor. That night John gave another tour of his home where I learned about Lee Godie from a small grid of photographs of hers that hung in John’s study. Lee Godie (1908 - 1994) was a self-identified Impressionist who worked anachronistically in the 1970s in Chicago, known for her paintings and photographic self portraits taken in photo booths. She appropriately spent a significant amount of time in and out of the Art Institute of Chicago which has an impeccable Impressionist collection, giving her a notorious reputation for Chicagoans who would see her working on the street. John proudly told a story of how he bought a painting from Godie off of Michigan Avenue, a feat considering that Godie stubbornly held onto her work. John knows so much about art in Chicago. He taught me about Joseph Yoakum (1890 - 1972), a trail guide for circuses in the early 1900s who wouldn’t start drawing until the 1950s, when he settled down in Chicago and drew delicate renderings of the country as he remembered it. Yoakum in influenced Jim Nutt’s work greatly, and Whitney Halstead would share Yoakum’s work with all of his students at the Art Institute of Chicago, influencing much of the Imagist’s works. The knowledge of Godie and Yoakum that John imparted on me gave me context for understanding Diane Simpson’s (b.1935, Joliet, IL) work when Matthew Higgs would introduce it to me almost a year later.

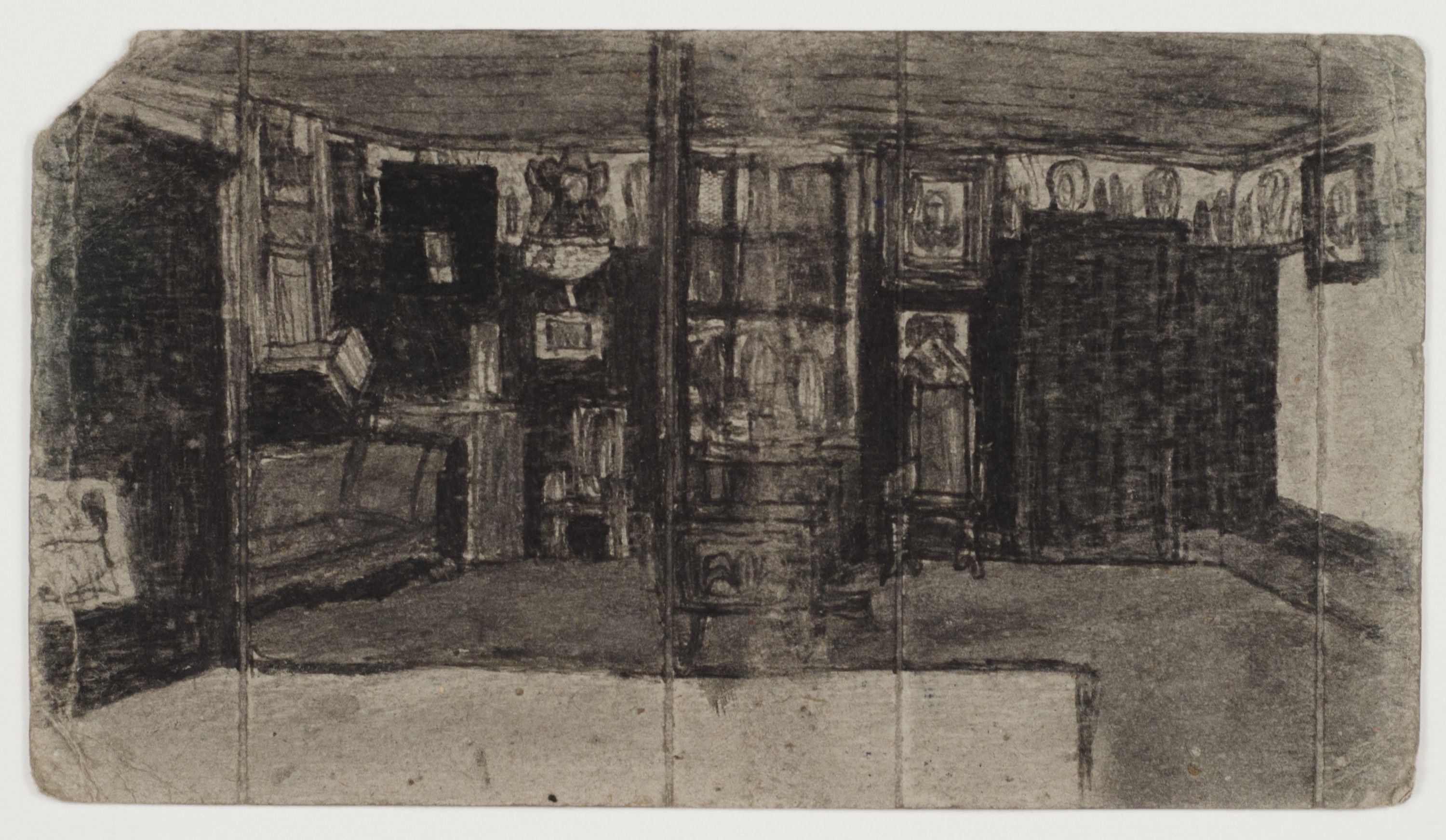

It was all too much to absorb in a single night, over the past ten years I have been returning to Philadelphia to John’s gallery where he tells me stories about the art he loves. John sometimes invites me to his storage room where he casually pulls Nazca ceramics off of shelves, carefully pointing out the variations on the surfaces of the objects in his collection. John has taught me about different techniques of conservation over the 20th century and that he always preferred the ones that were only gently cleaned leaving the slightest amount of dust from the original site, detesting when conservators over polished the ceramic or covered the surface in shiny wax. No matter what the object was, whether it was a gnarly Memory Jug or a delicate Ramirez, John always punctuated the presentation of an object with, “Isn’t it fantastic?” He has an adoring gaze to the objects he loves, that is unparalleled in the world of art dealers. John has taught me about the Philadelphia Wireman and how they were found in a dumpster on South Street in Philadelphia by a chance ash of a car’s headlight hitting a reflector in one of the small sculptures. John taught me about Eugene Von Bruenchenhein (1910 - 1983) and that all of his sculptures were made from the mud of his backyard and cooked in his own kitchen oven. John taught me about James Castle (1899 - 1977), and how he would mix soot with his own saliva to make drawings or how he would pulp the color out of found advertisements, print media or mail, again mixing it with his own saliva to add color to his works.

I know a lot of what I know about the artists in Dear John because of what John has told me, and less because of what I have read about them. He imparts on me, and continues to daily, an oral history that is so specific to his style of art dealing. He devotes his life to telling the stories of those disenfranchised by the educational system and the art world. Ten years after his 40th anniversary exhibition, and nine years after owning my own gallery, it is with gratitude and appreciation that we honor John with this 50th anniversary show.

Coinciding with the presentation at JTT be a companion exhibition at Adams and Ollman (Portland) and an online archival presentation by Fleisher/Ollman.

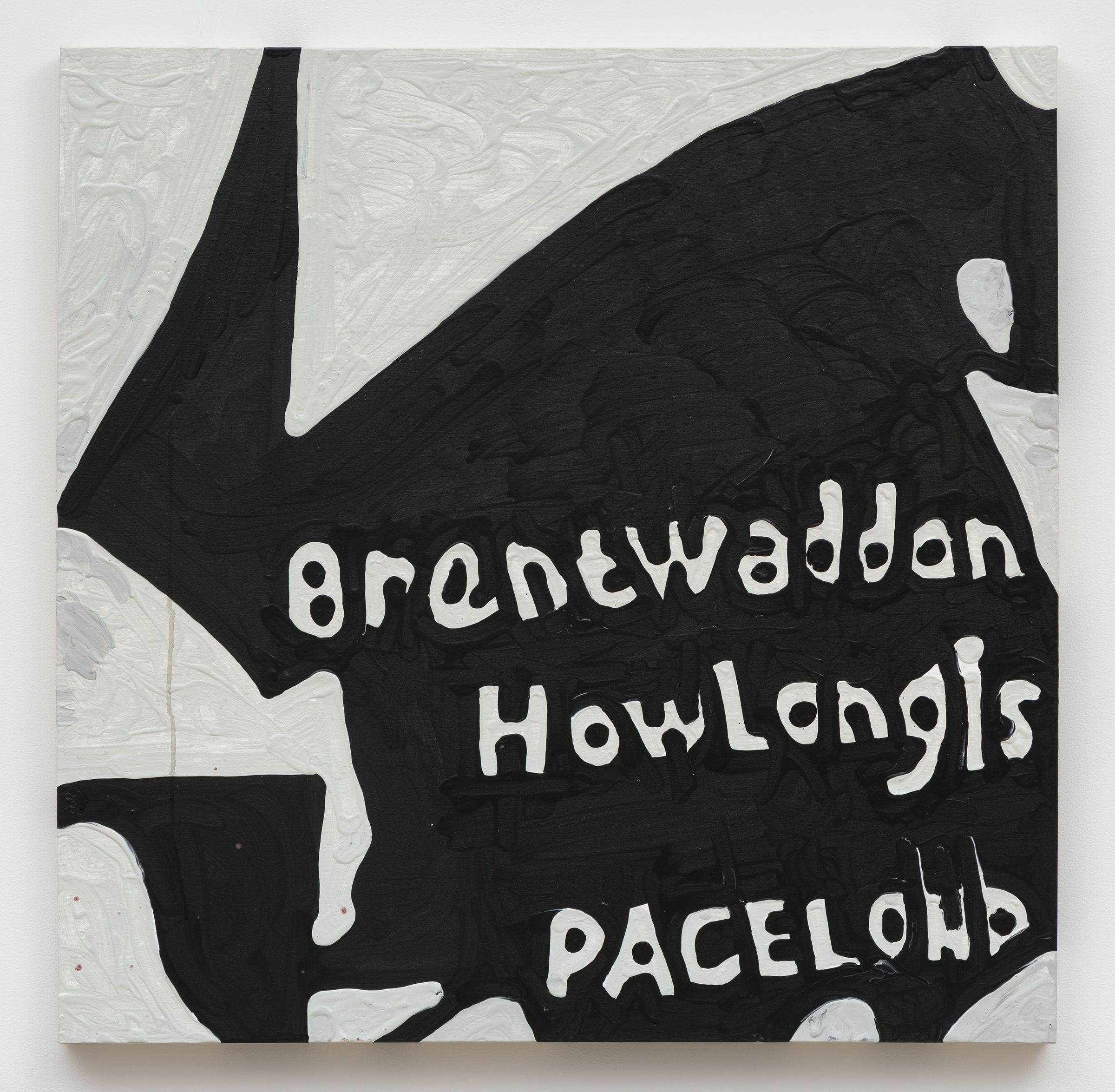

untitled, 2016

acrylic on canvas

36 x 36 in

91.5 x 91.5 cm

Hun Bank, 1983

enamel on masonite

48 x 39 in

122 x 99 cm

Untitled (Interior with Stove, Framed Pictures), n.d.

soot and saliva on found paper

5 x 9 in

12.5 x 22 cm

(Title faded), n.d.

colored pencil and ballpoint pen on paper

11.5 x 17.5 in

28.5 x 44.5 cm

Collar (Pagoda), 2013

painted aluminum, linoleum, rivets

56 x 30 x 16.5 in

142 x 76 x 42 cm

Untitled (Nurse), c. 1940

carved limestone

14 x 6 x 7 in

35.5 x 15 x 18 cm

Untitled (Nurse), c. 1940

carved limestone

14 x 6 x 7 in

35.5 x 15 x 18 cm

Red Dog/Irish Setter (Red Dog Silver), n.d.

painted deck of cards, silver wire, graphite and varnish on paper

10 x 17 x 1 in

25.5 x 43 x 2.5 cm

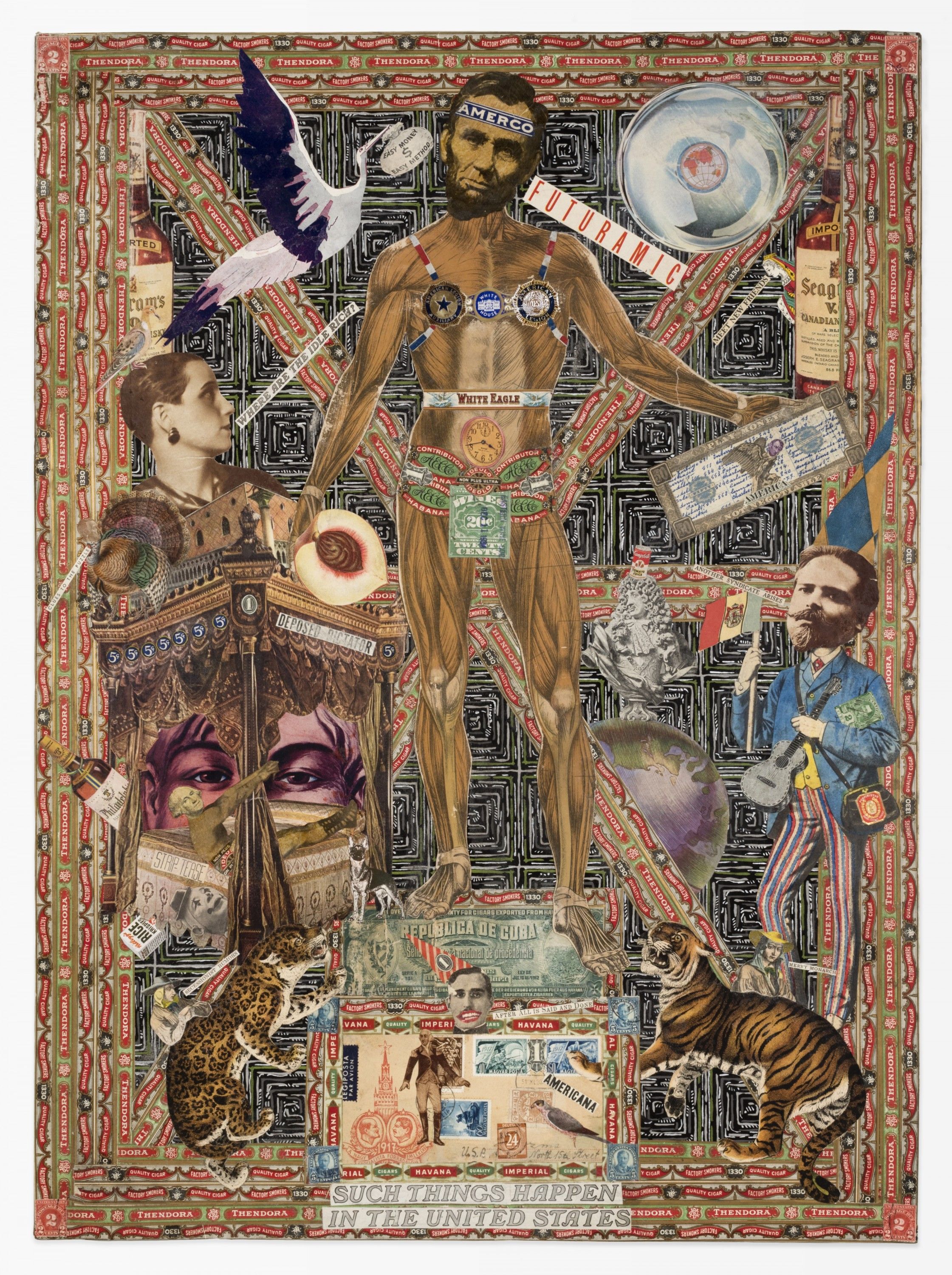

Such Things Happen in The United States, c. 1920-1960s

mixed media collage on paper

30 x 22 in

75.5 x 55.5 cm

Untitled (Straw, blue plastic pen cap), c. 1970-75

wire, found objects

4.5 x 1 x 1 in

11 x 2.5 x 2.5 cm

Untitled (wire, cellophane, red plastic), c. 1970-75

wire, found objects

2.5 x 1.5 in

6.5 x 4 cm

Untitled (doorknob, nail, wire), c. 1970-75

wire, found objects

5 x 3.5 x 2 in

12 x 9 x 5 cm

Untitled (Masking tape drawing, yellow stopper), c. 1970-75

wire, found objects

5 x 2.5 x 2 in

12.5 x 6.5 x 5 cm

Untitled (wire, plastic ribbon, paper), c. 1970-75

wire, found objects

3 x 2.5 in

7.5 x 5.5 cm

Untitled (Peach Vessel with open top), n.d.

painted clay

8 x 5 x 5 in

20.5 x 12.5 x 12.5 cm

Untitled (Pink Vessel), n.d.

painted ceramic

7.5 x 5.5 x 5.5 in

19 x 14 x 14 cm

Untitled (Eight Self Portraits), c. 1980

unique photograph

5 x 4 in

12.5 x 9.5 cm