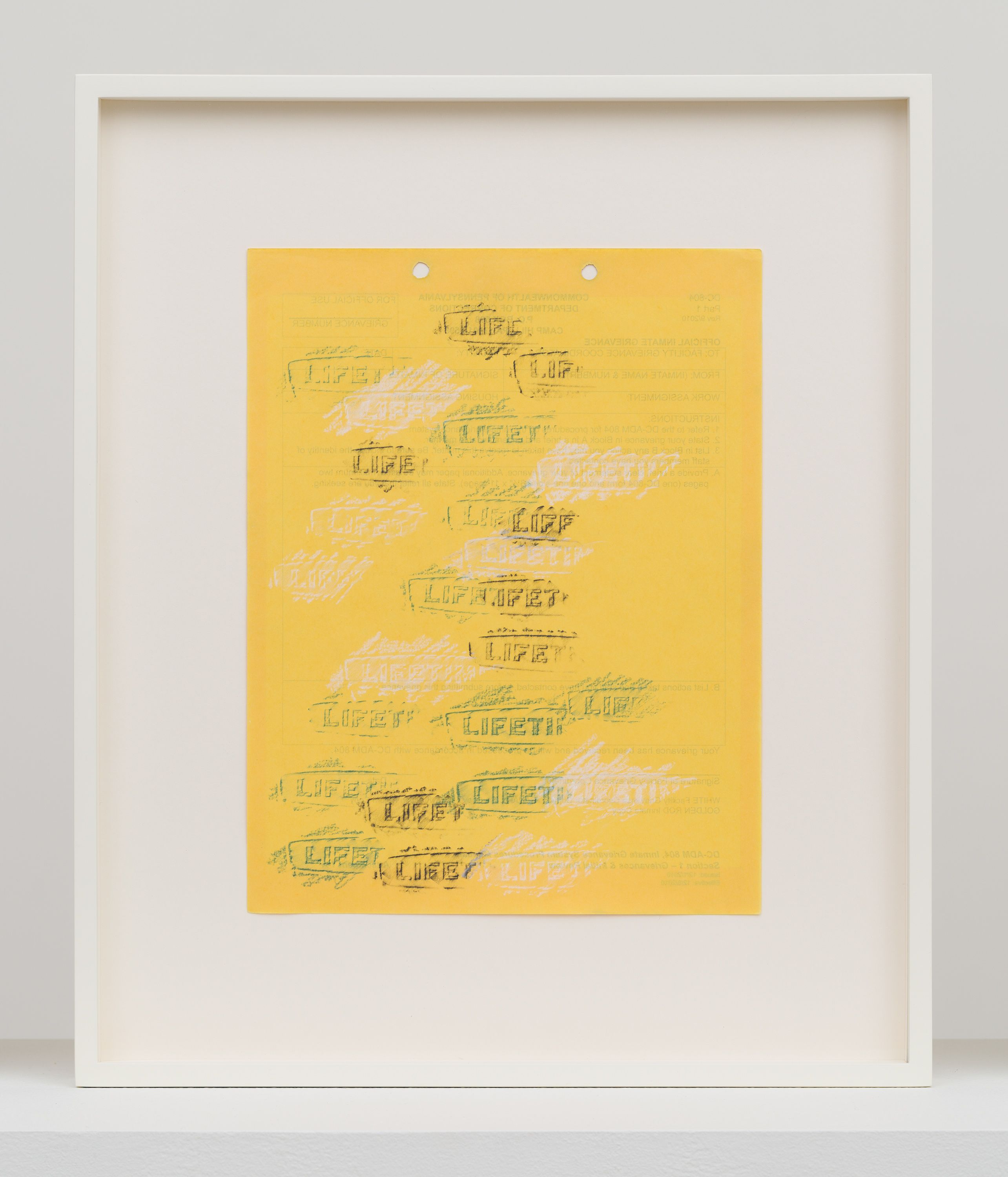

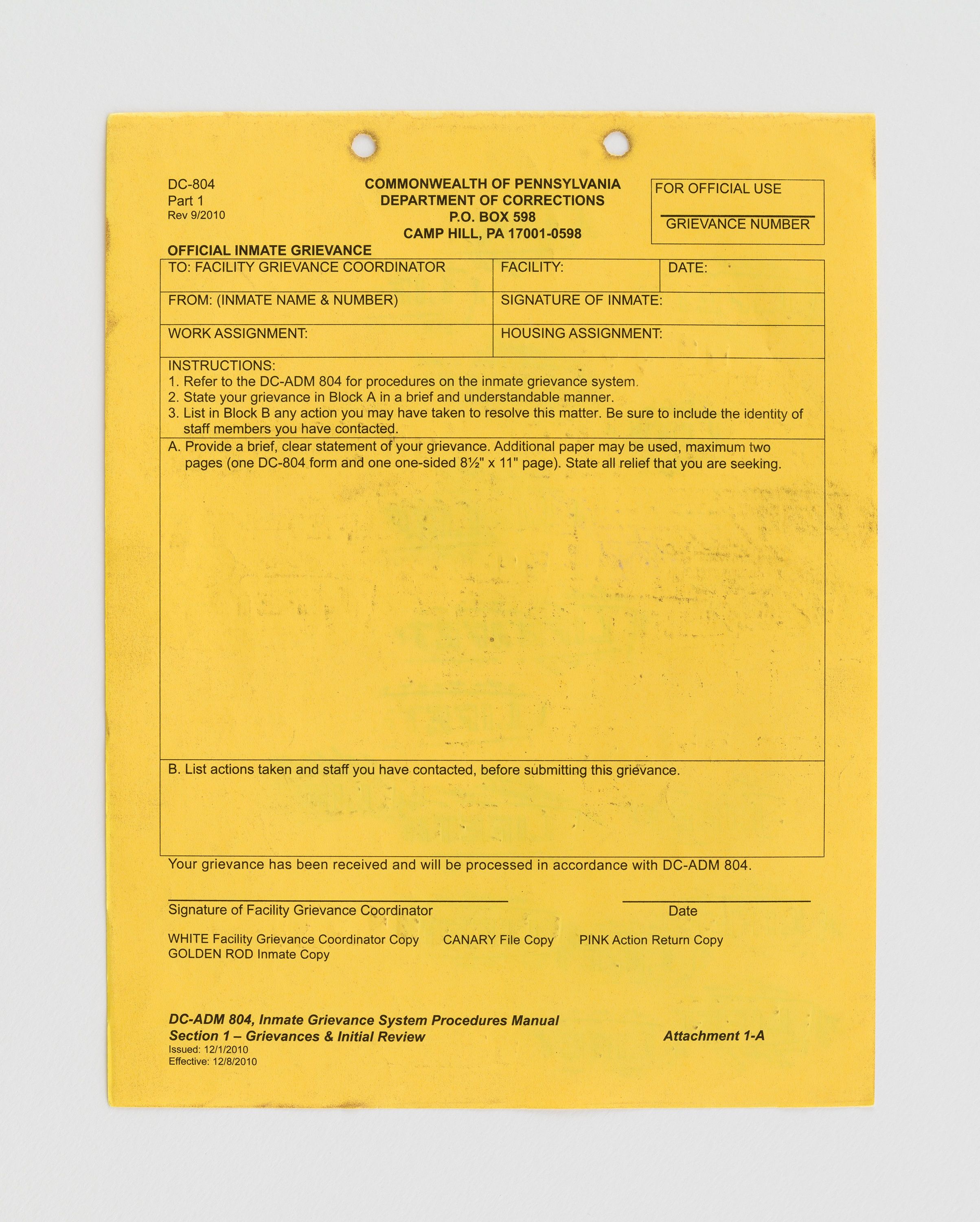

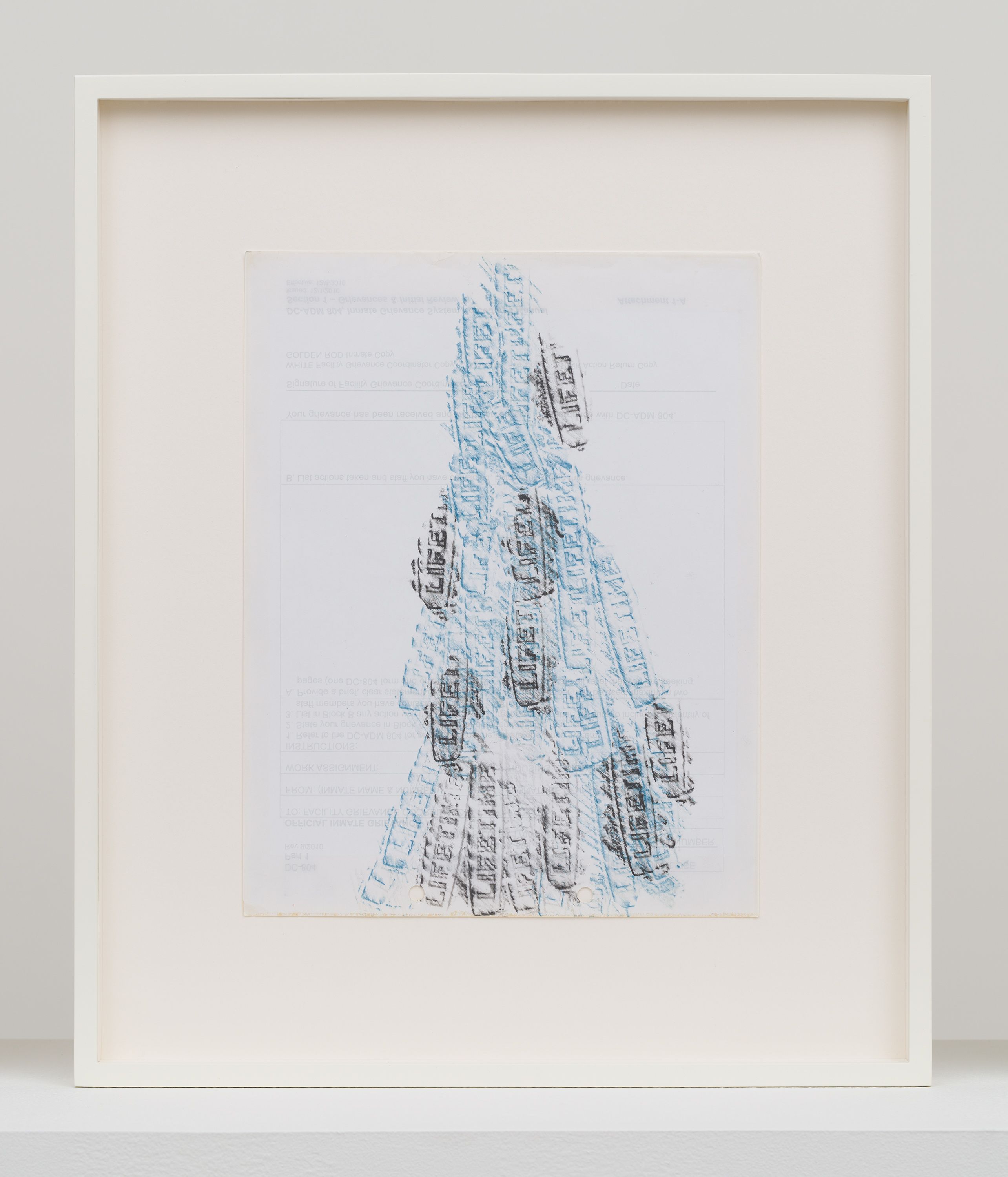

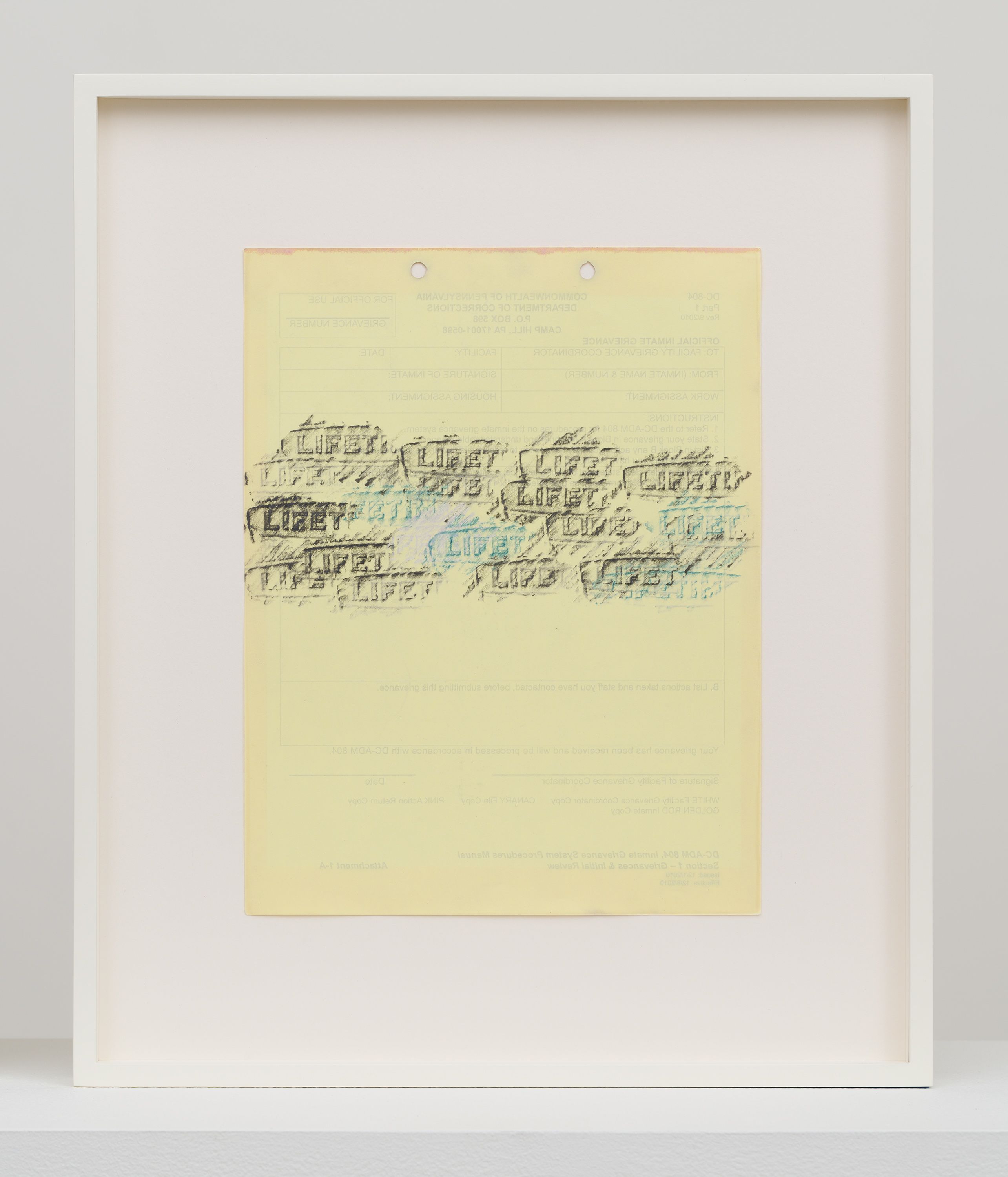

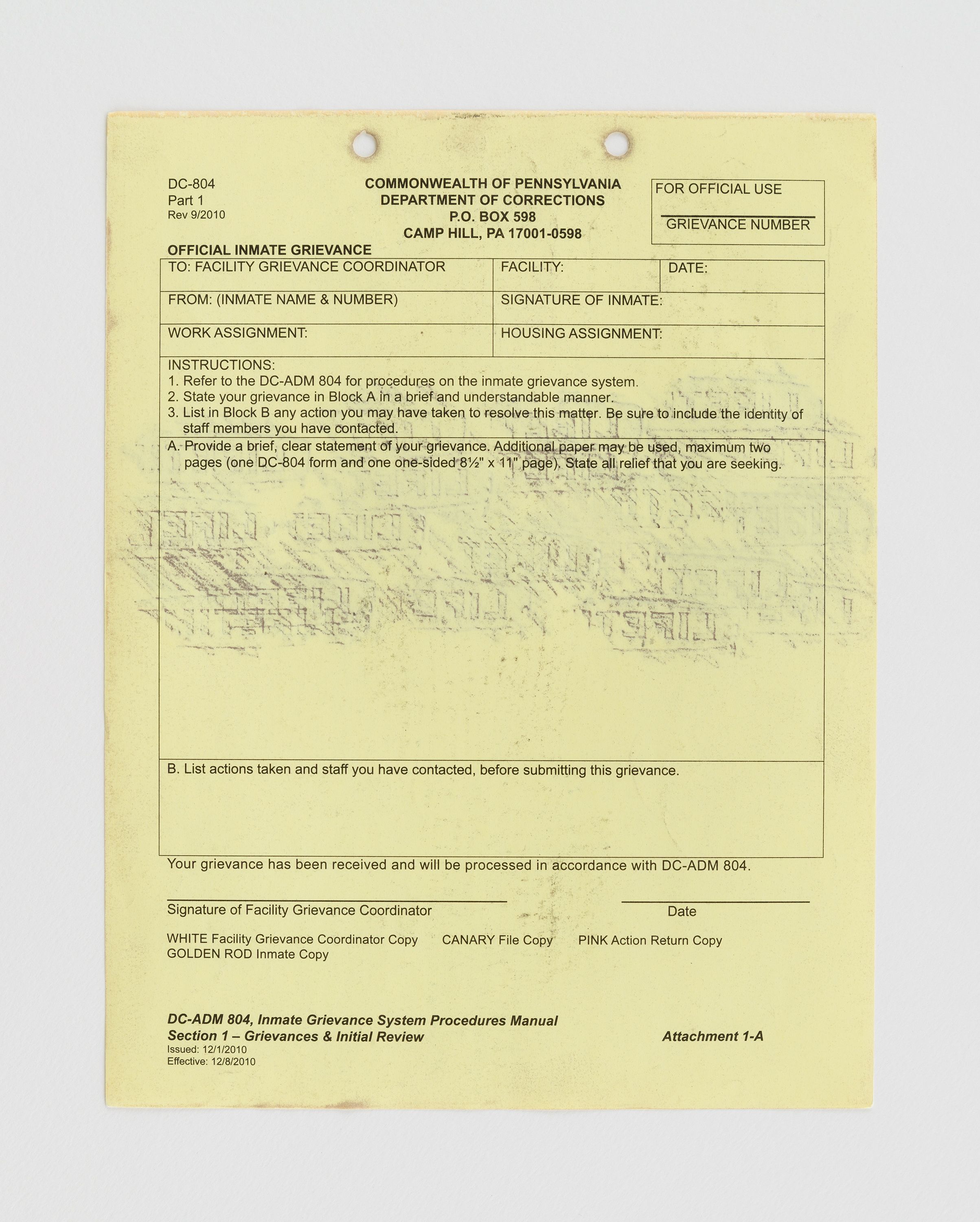

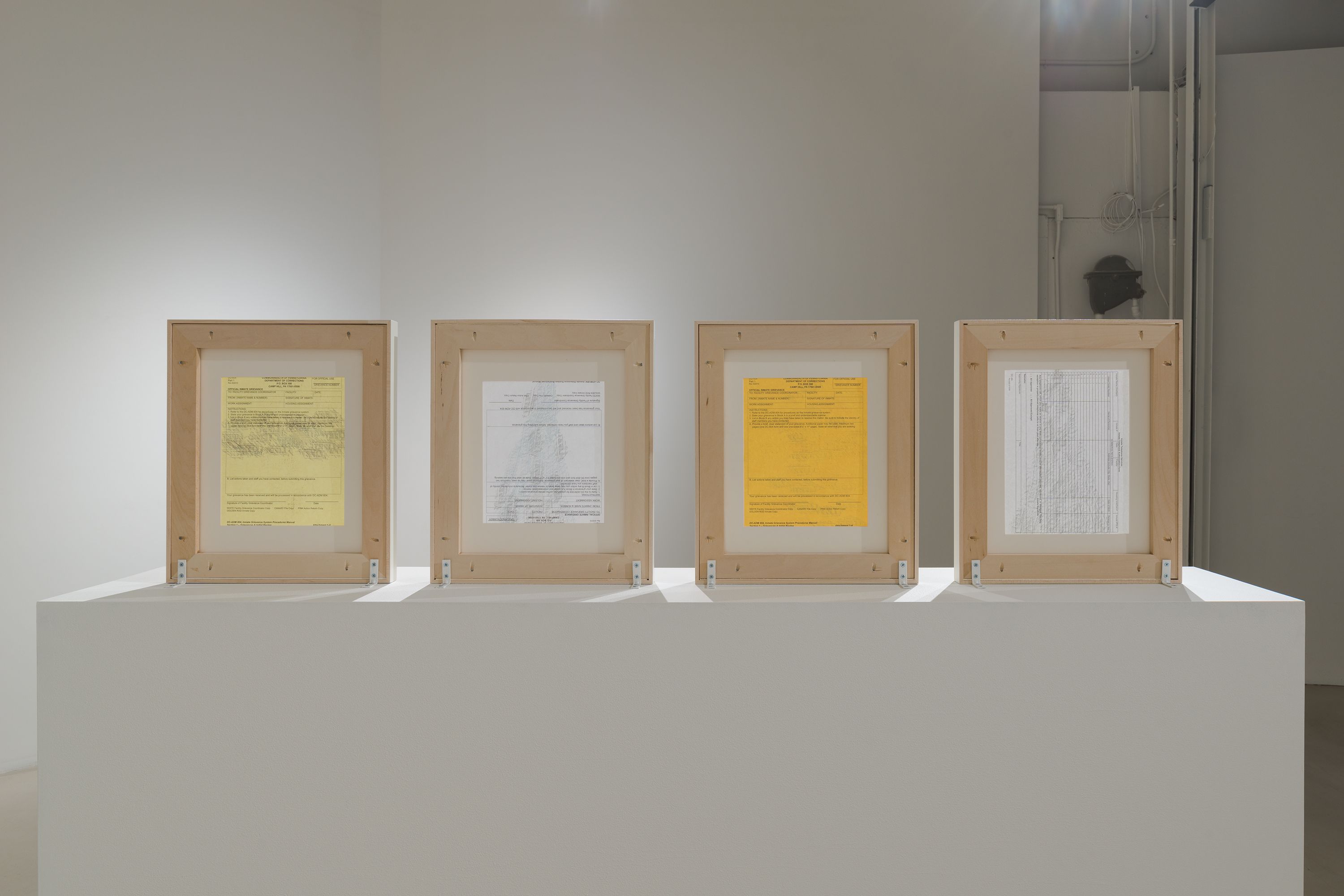

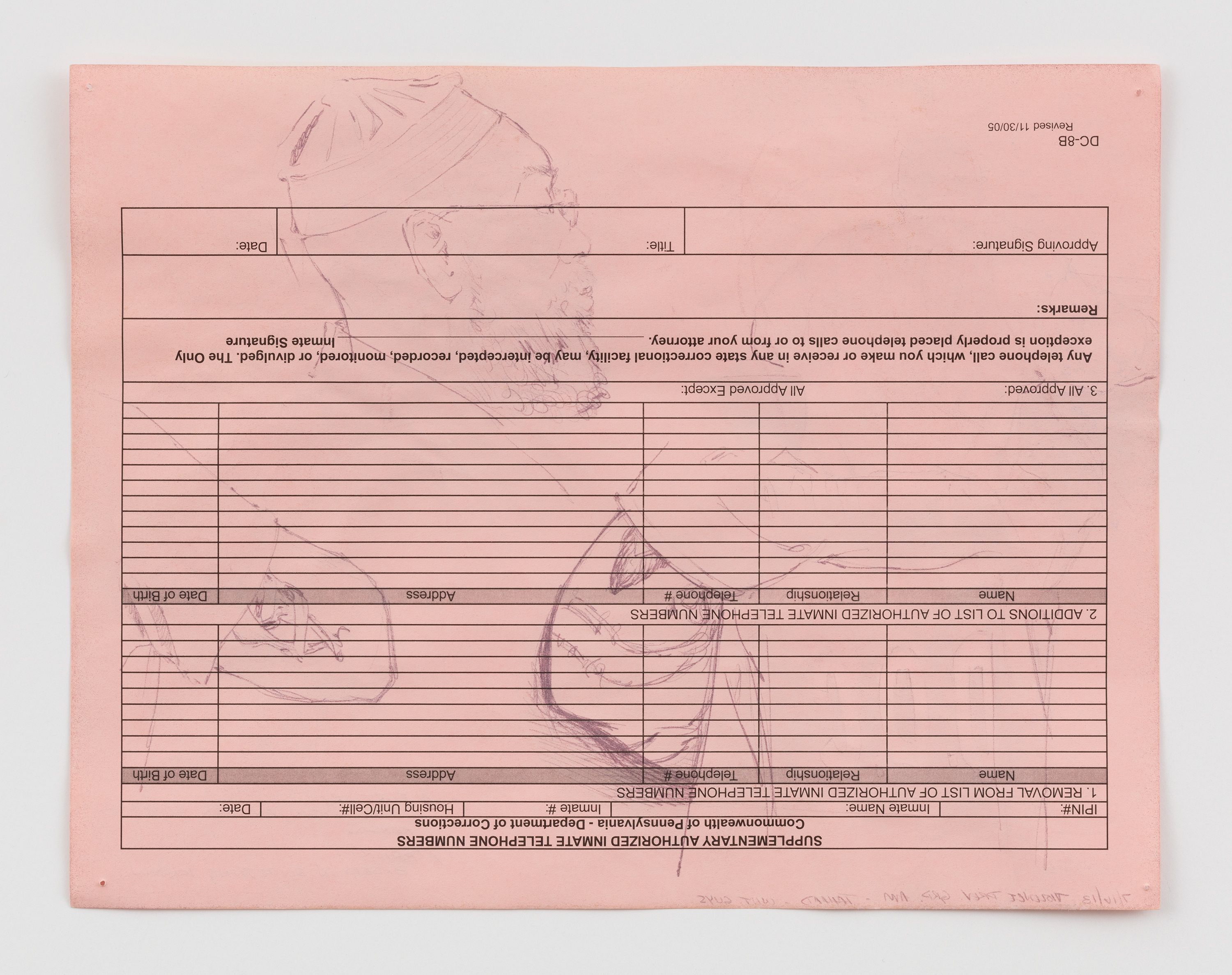

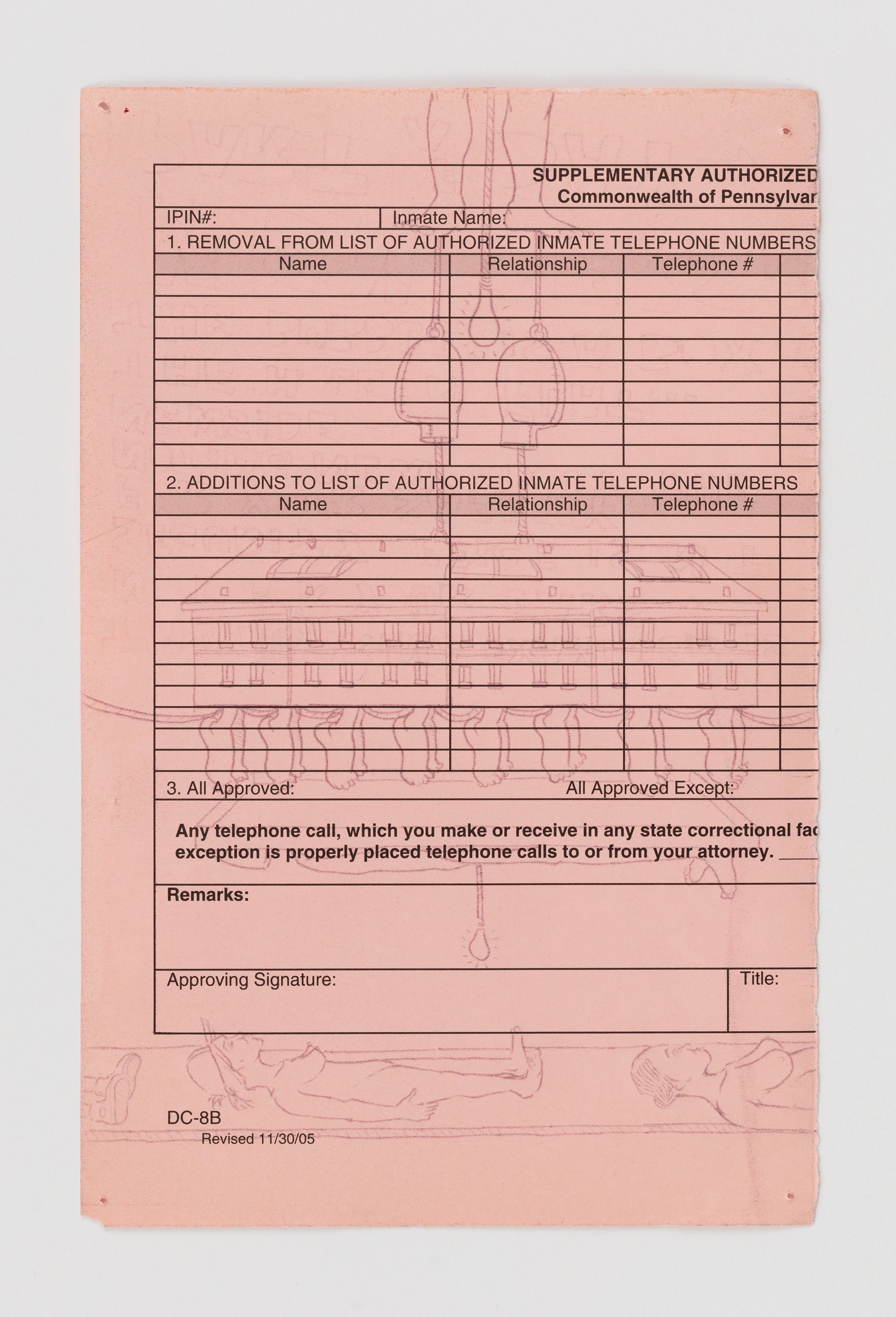

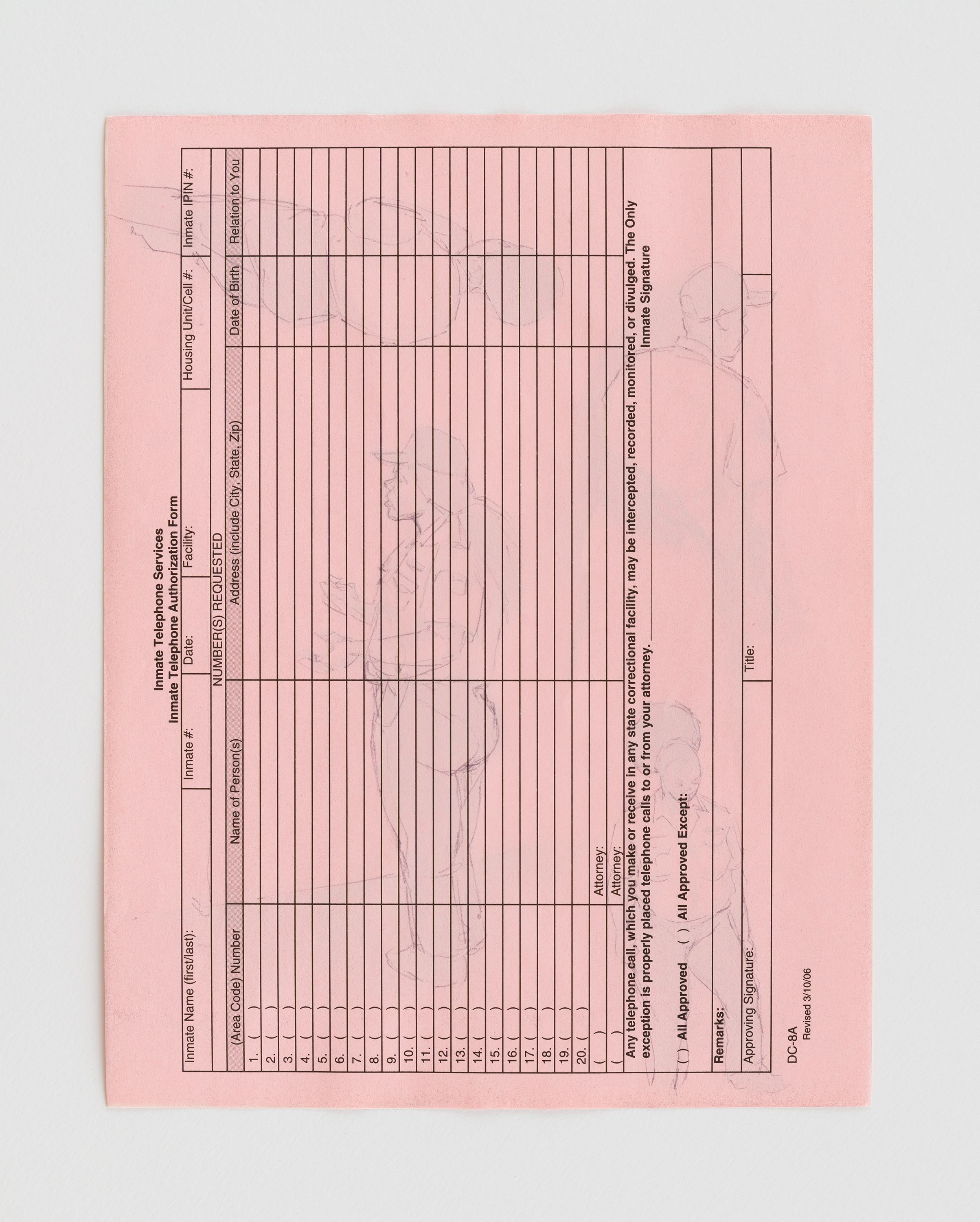

JTT is proud to present its second solo show with James Yaya Hough (b. 1974, Pittsburgh, PA), Grievance, a selection of 45 drawings and watercolors from his larger Invisible Life series. At the entrance of the gallery are several rubbings in black, blue and white colored pencil on the back of Inmate Grievance forms. The rubbings trace an embossed logo of a plastic folding table that reads “lifetime”.

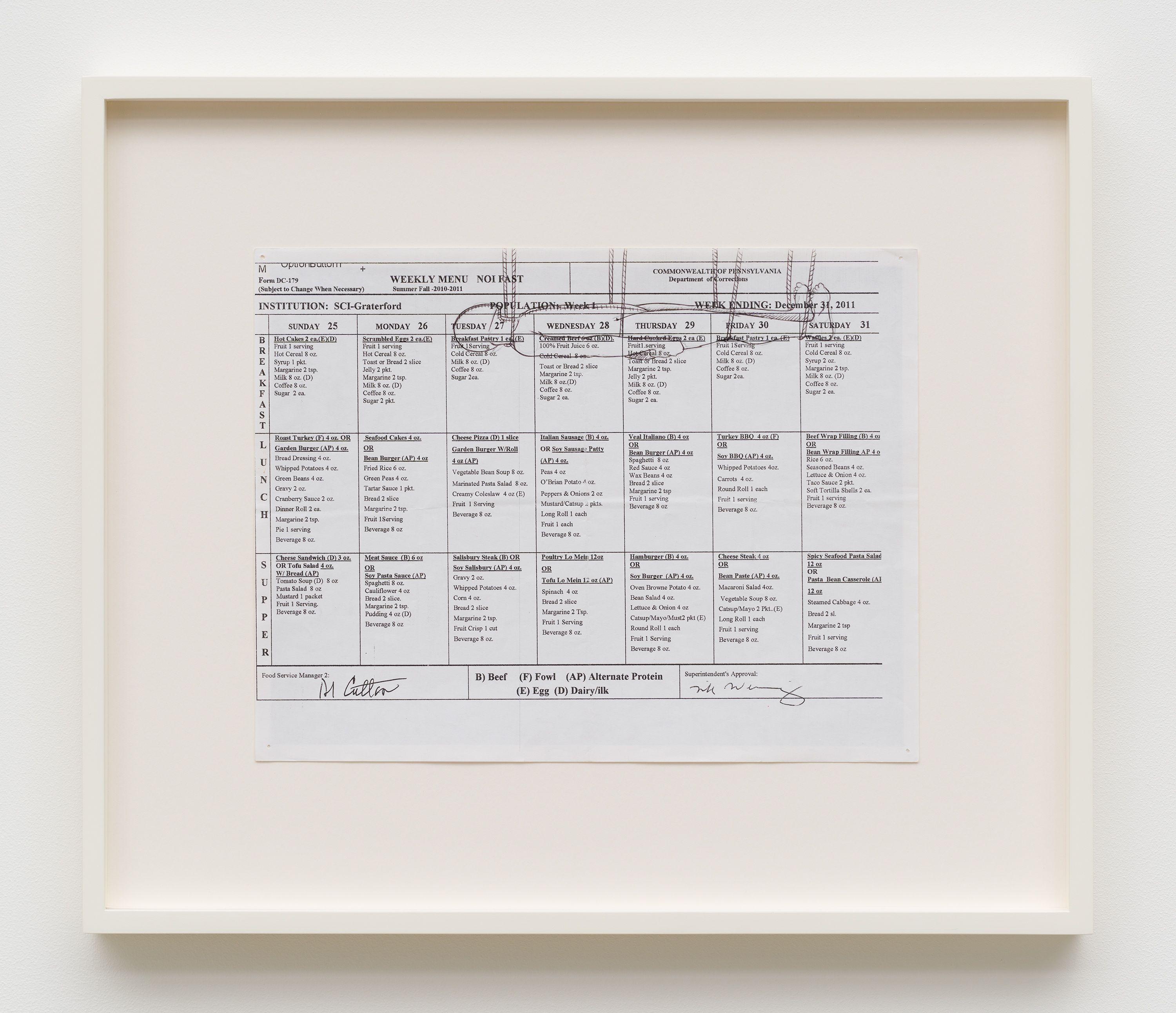

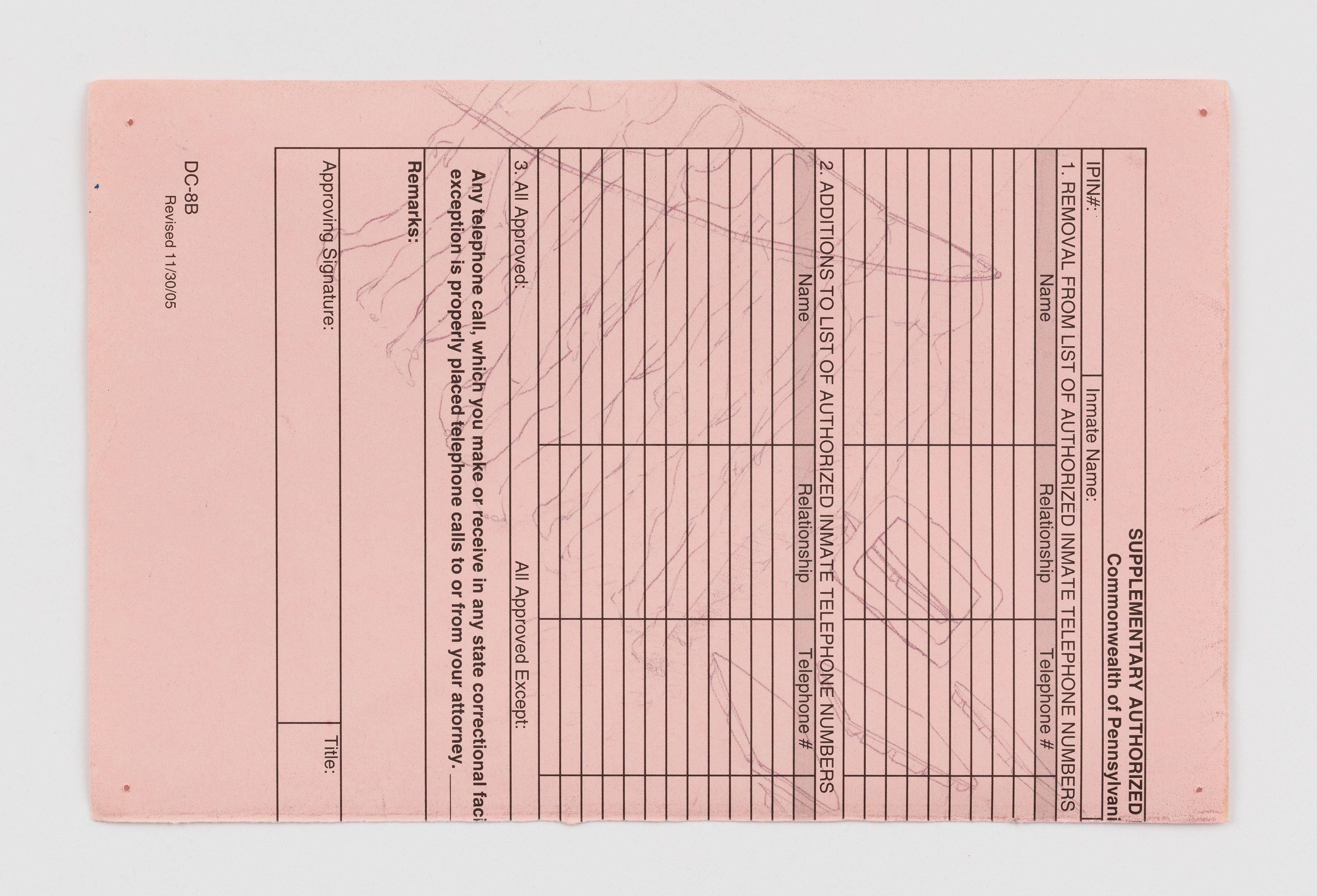

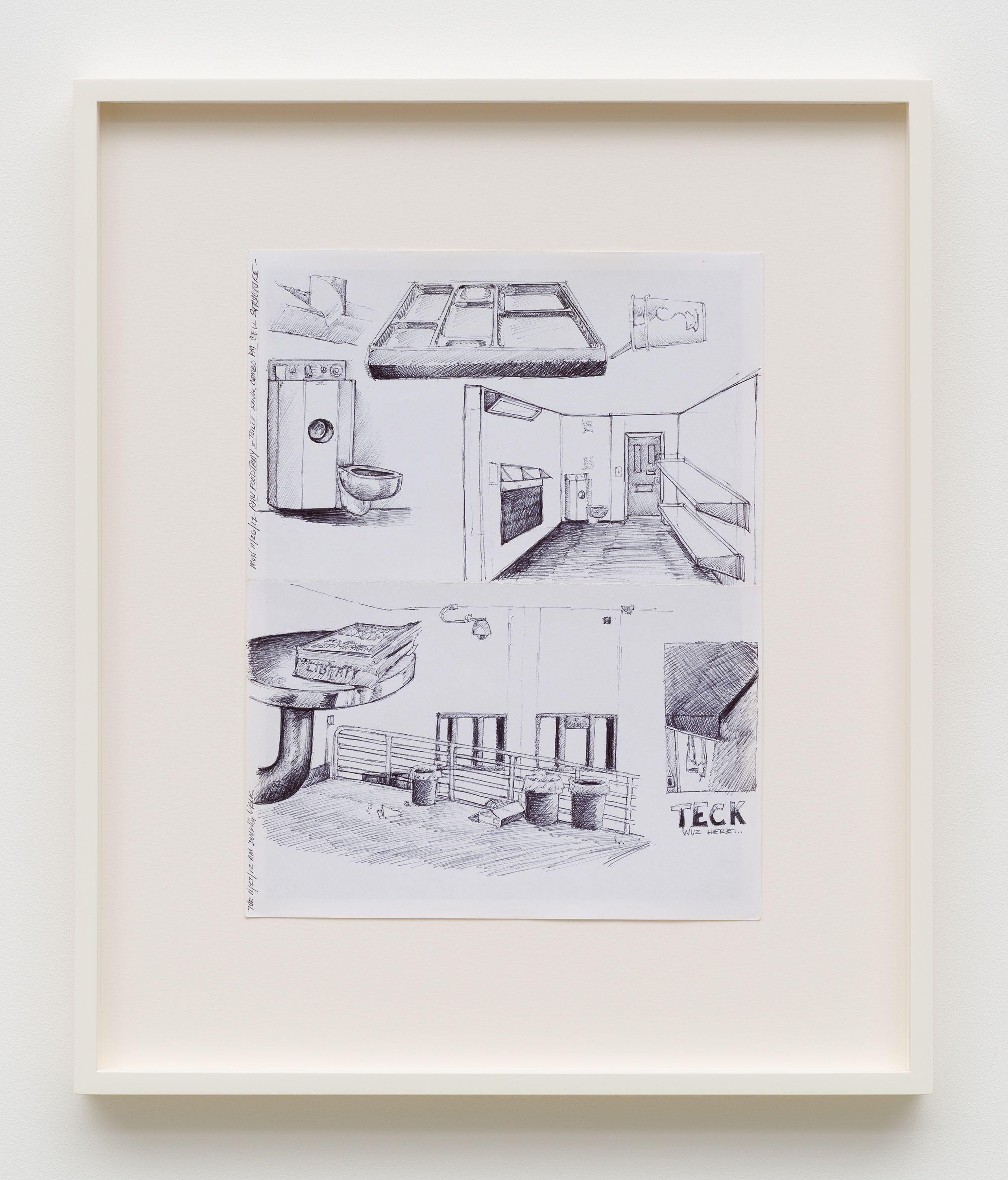

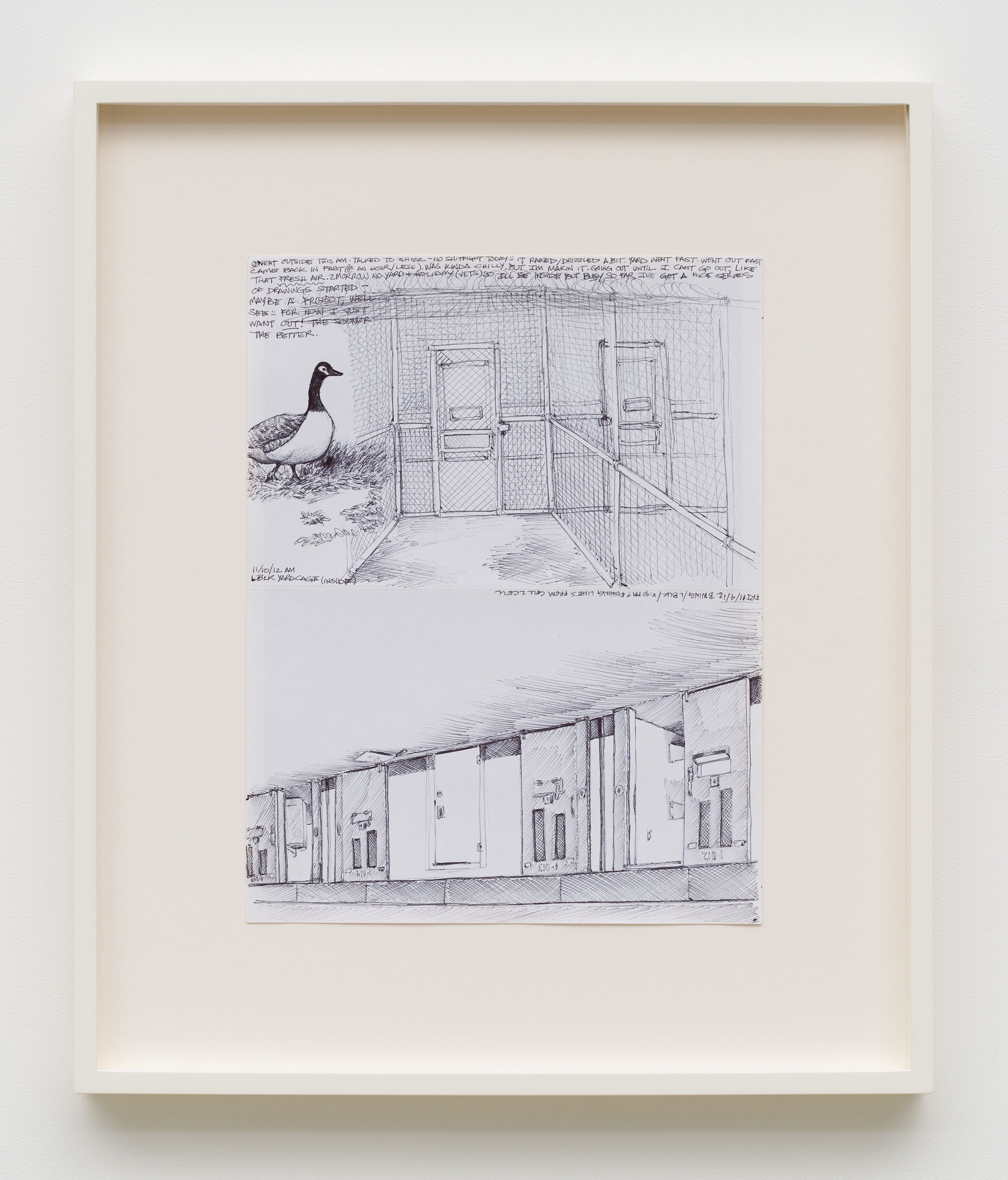

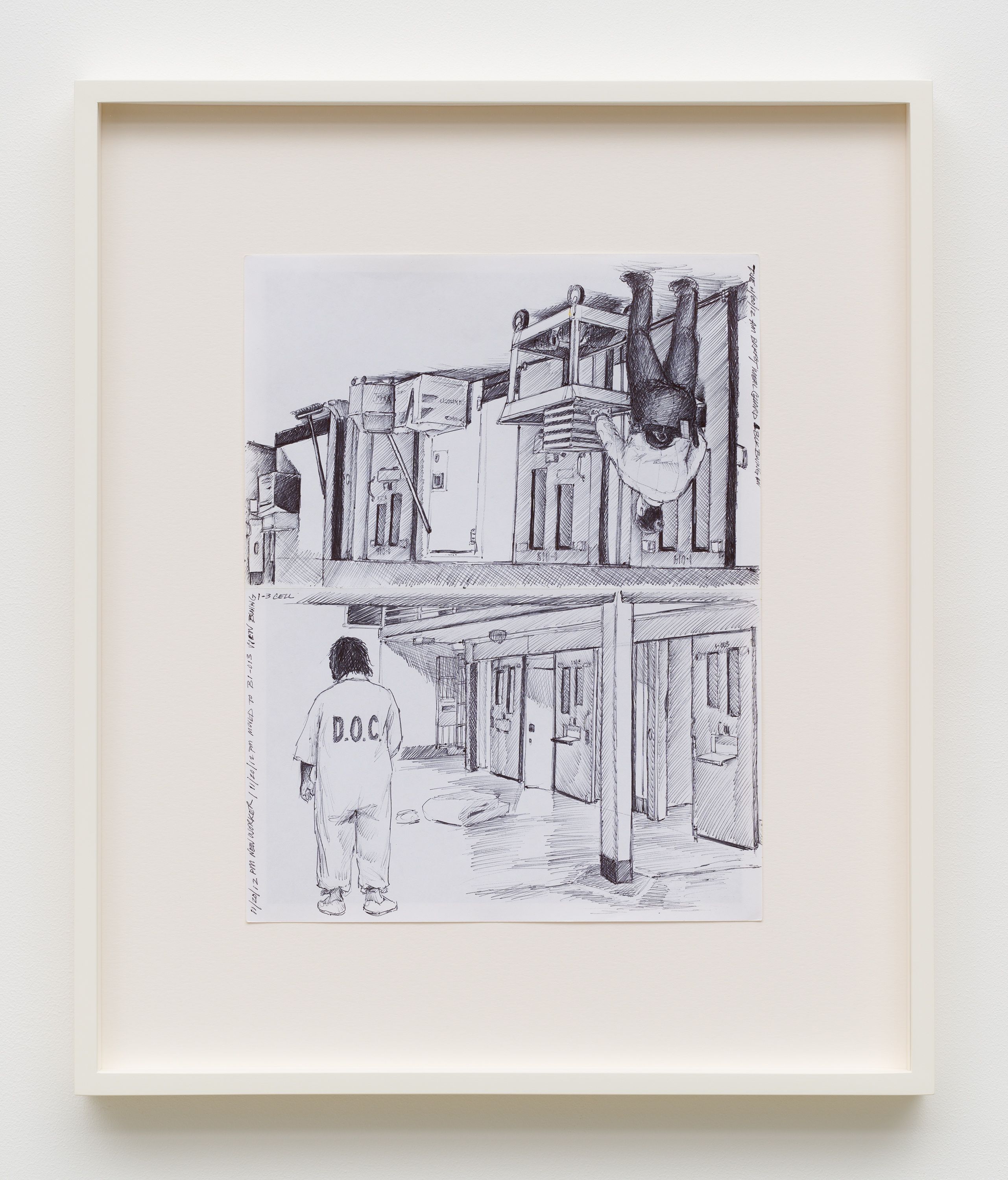

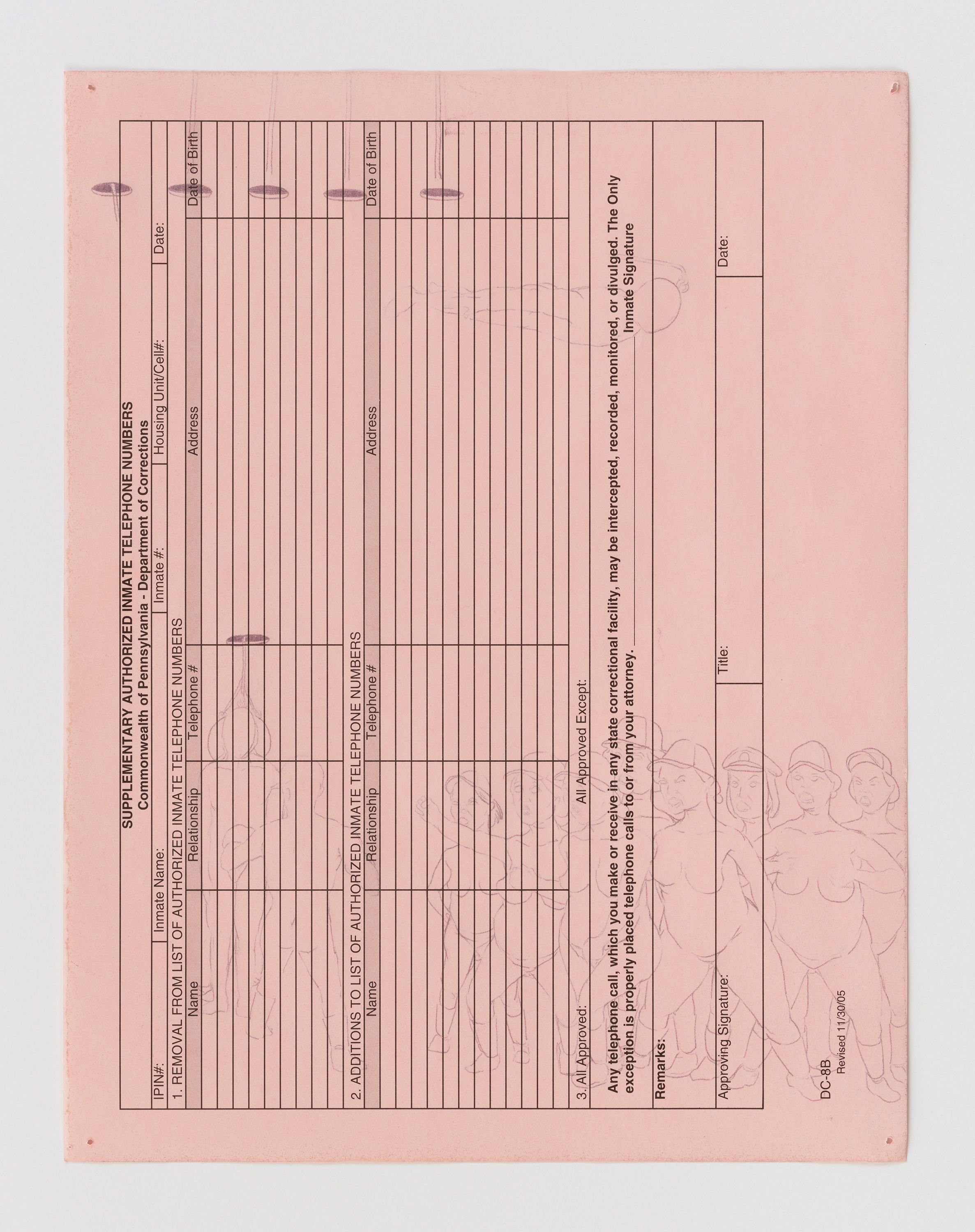

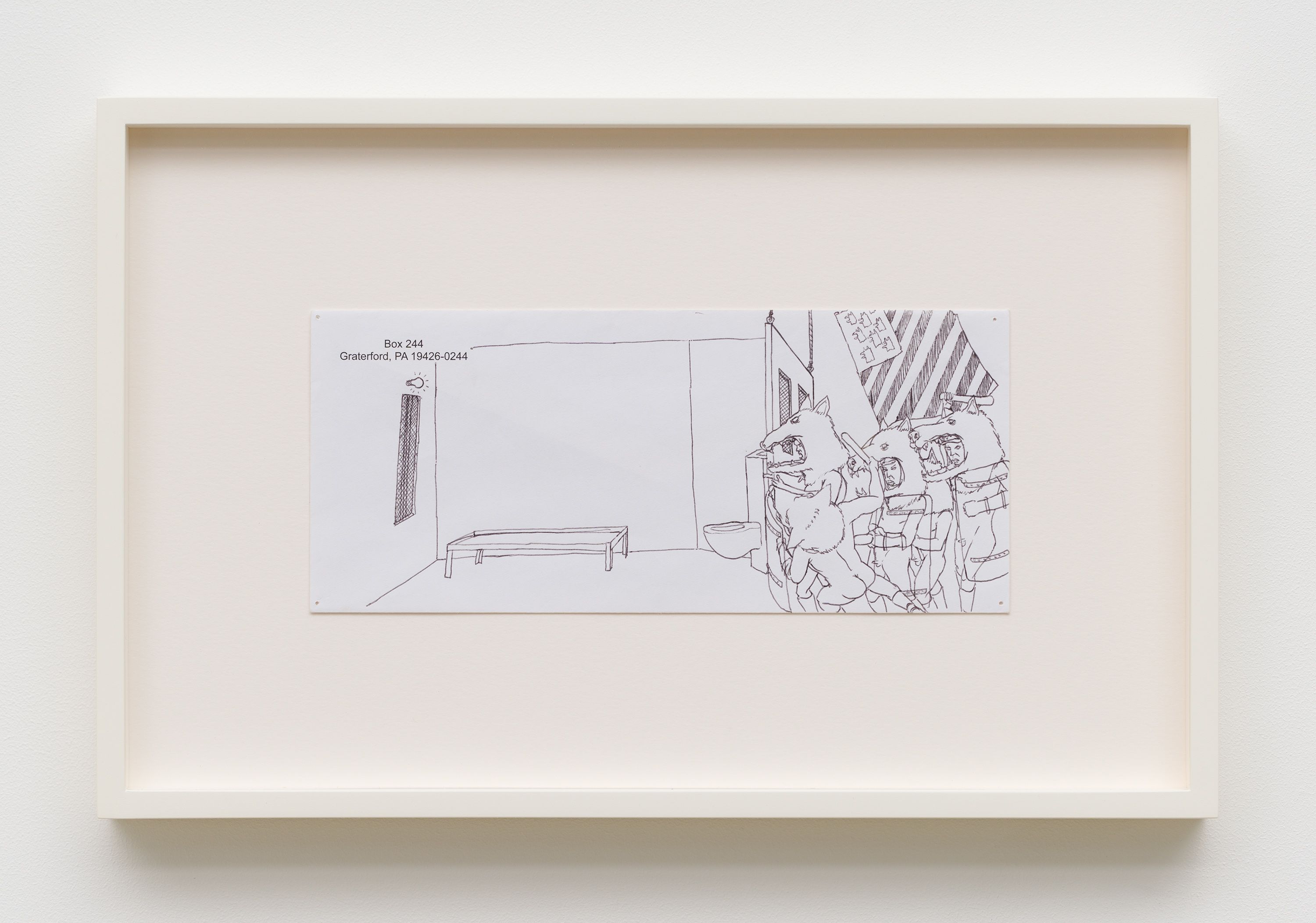

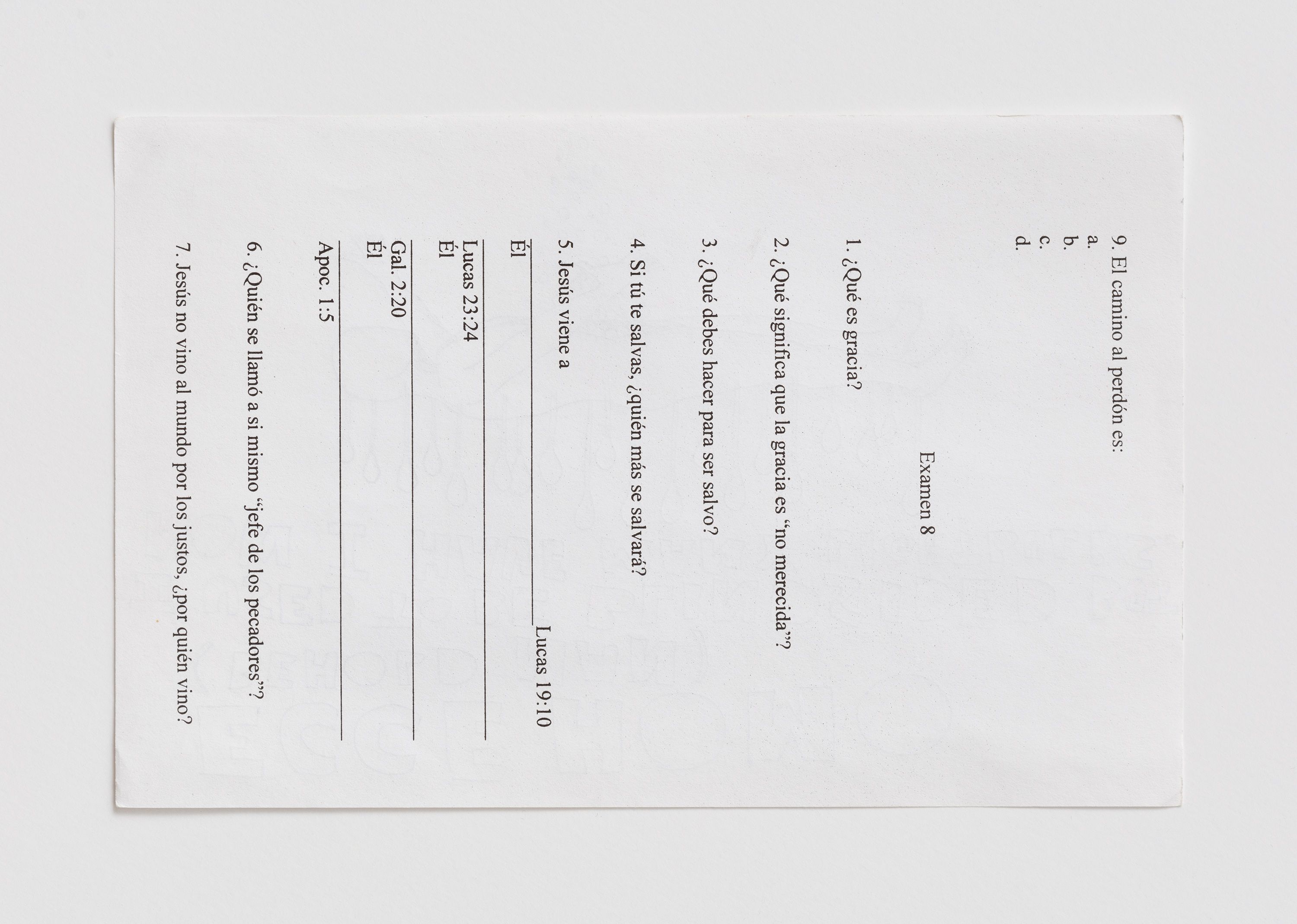

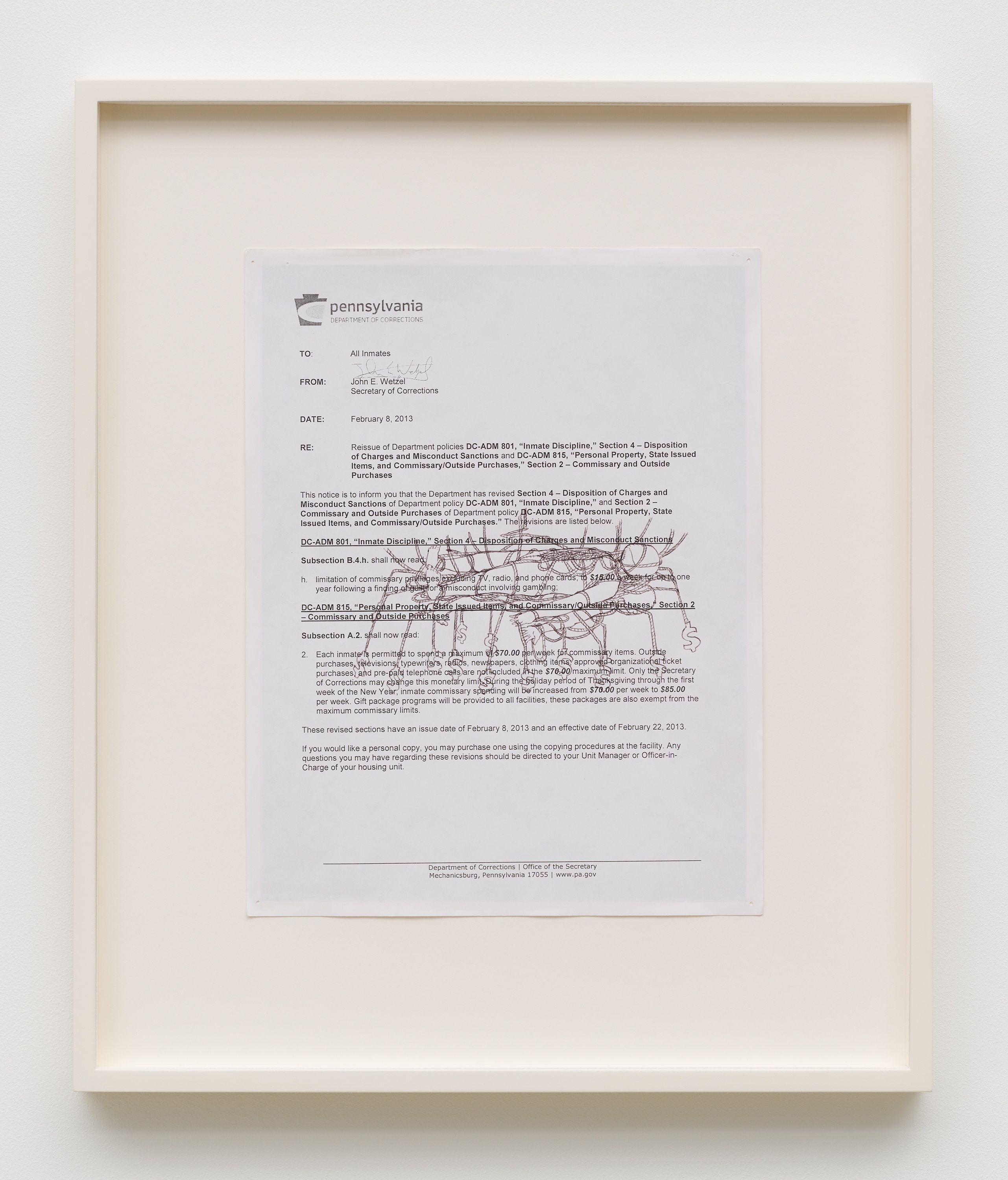

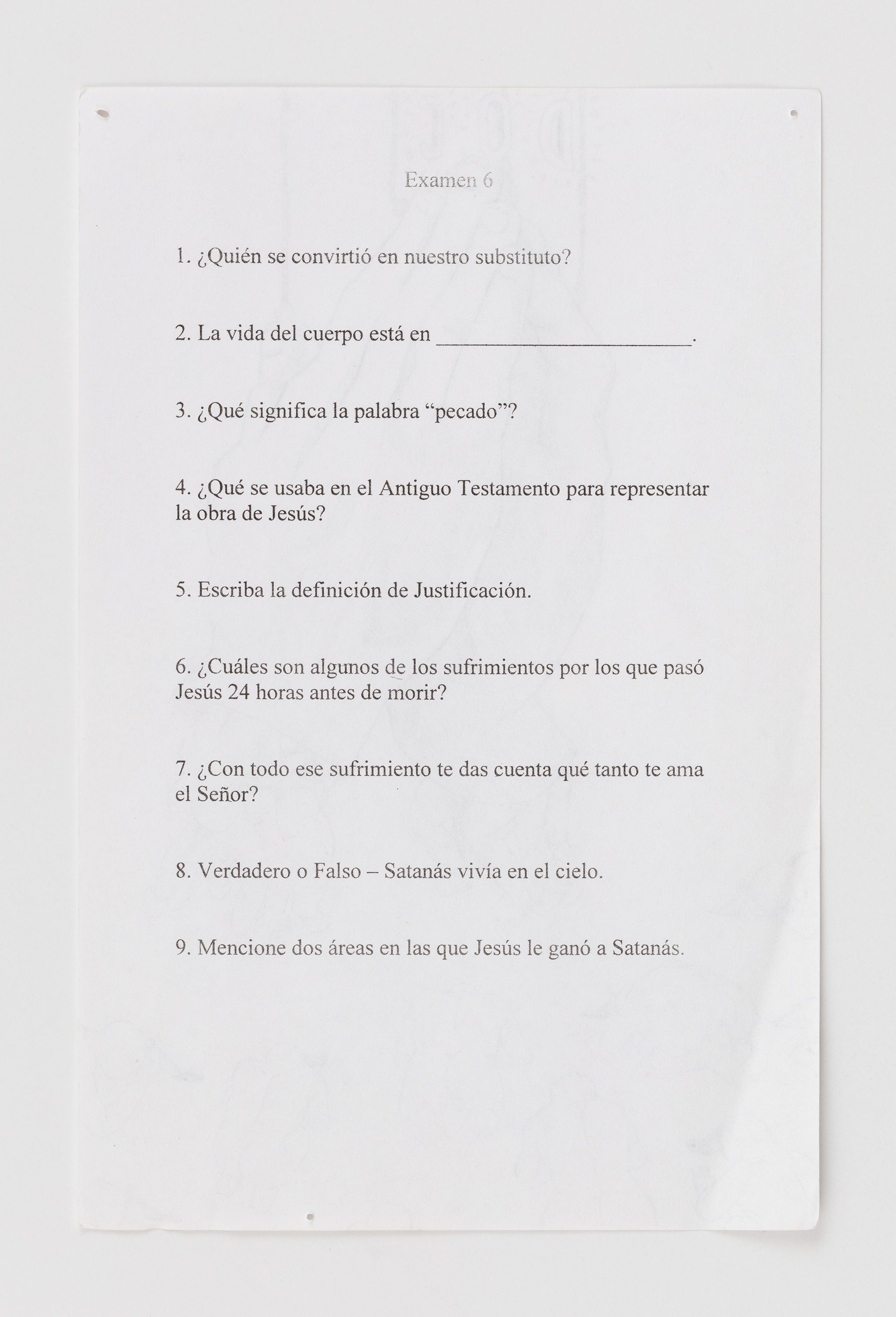

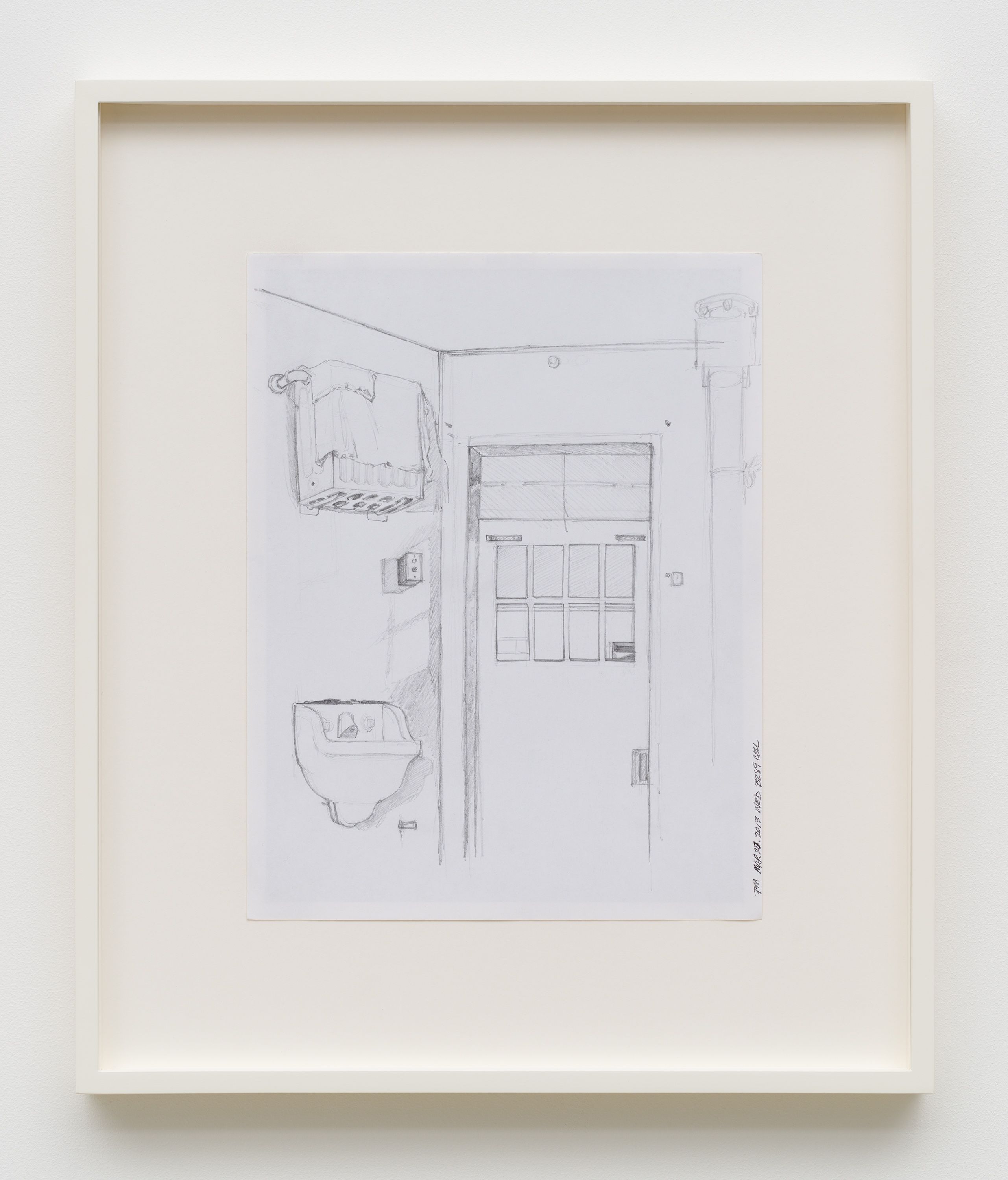

While Hough considers it an ongoing series, most of the works from the Invisible Life series were made while Hough was incarcerated in Graterford Prison from 1993 to 2019, with the series being made mostly between 2008 and 2016. The paper used for these works comes from the documents he was handed during his sentence including Inmate Telephone Authorization Forms, Authorized Visitors Lists, Weekly Menus from the cafeteria, Dental Sick Call Requests, lists of Christian trivia in Spanish and Official Inmate Grievances. An Official Inmate Grievance purports to allow the inmate to file a grievance to the facilities where they are held about any number of issues, such as the inappropriate behavior of a guard, a complaint against a cellmate, a request to move cells, a lack of access to the yard or poor quality of food in the cafeteria. The simple technology of triplicate paper allows for inmates to submit their complaints in writing while the form separates into different divisions of the filing system. While the form presents itself as democratic, offering the inmate an opportunity to advocate for their own needs, it is usually ignored by the facility or lost in the filing system. In many cases, submitting the form endangers the inmate, accelerating the contention already inherent within their relationship to the institution.

In 1992, Hough was given a life sentence at the age of 17. After serving a year at a juvenile detention center, he was sent to Graterford Prison, which was the largest maximum security prison in Pennsylvania at the time. In 2012, 20 years after Hough’s initial incarceration, a Supreme Court case found that granting juveniles a life sentence violates the 8th amendment.[1] Even so, Hough was not released after the ruling. He had to submit multiple requests over a 7 year period until 2019 when he was given parole. Bureaucracy is an efficient way for the carceral system to maintain an inmate’s capture due to its archaic technology that delays processing basic rights to individuals.

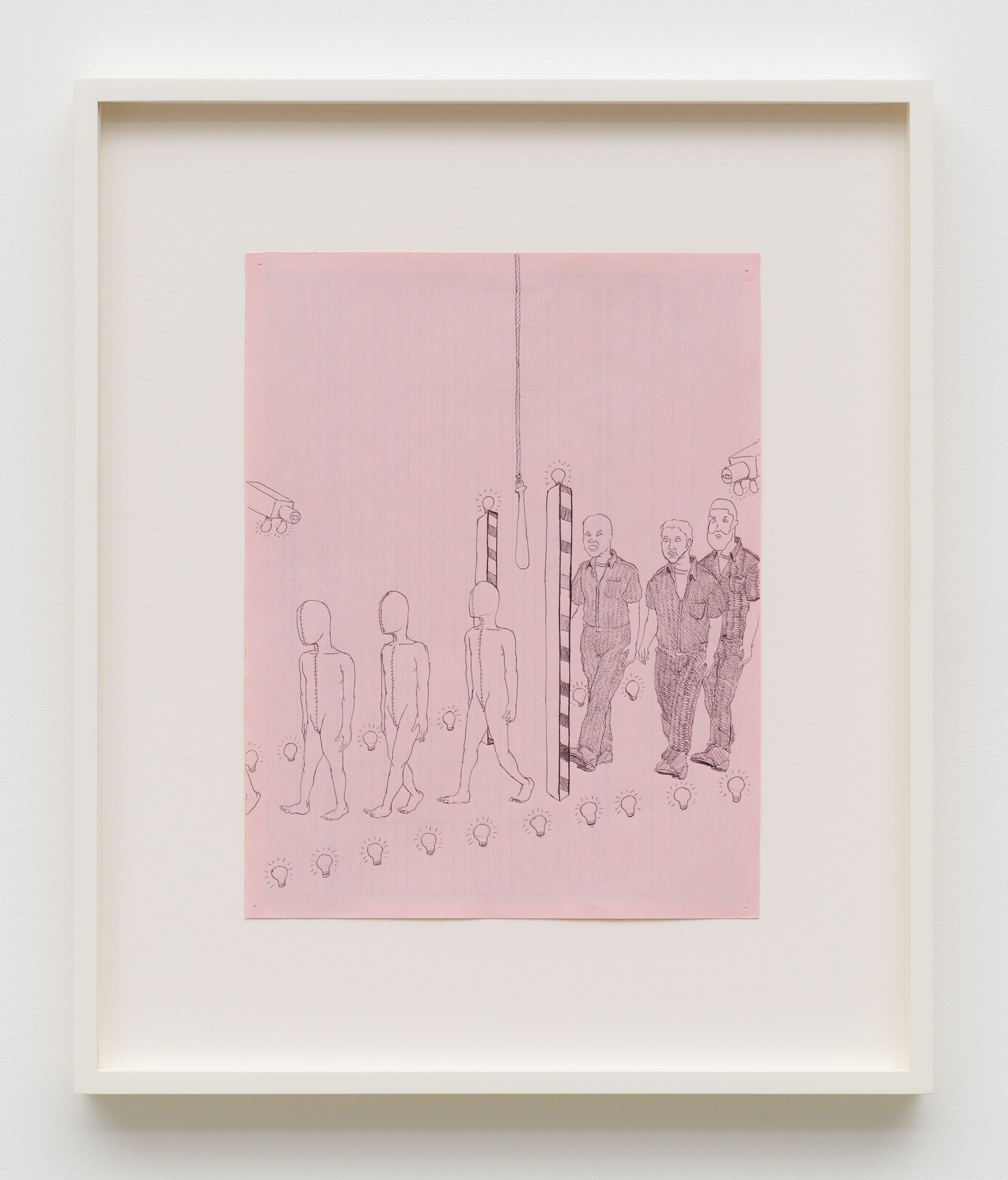

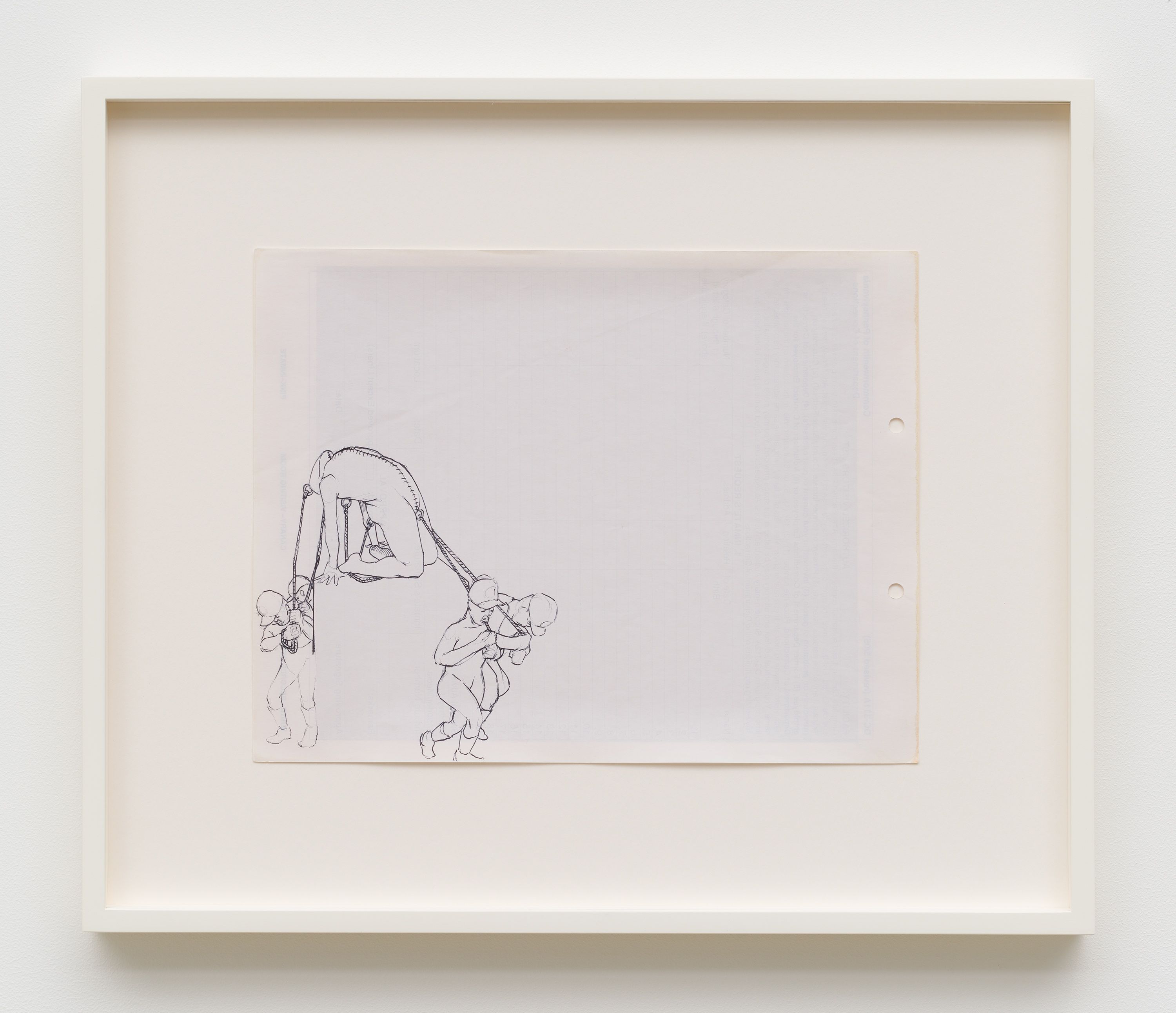

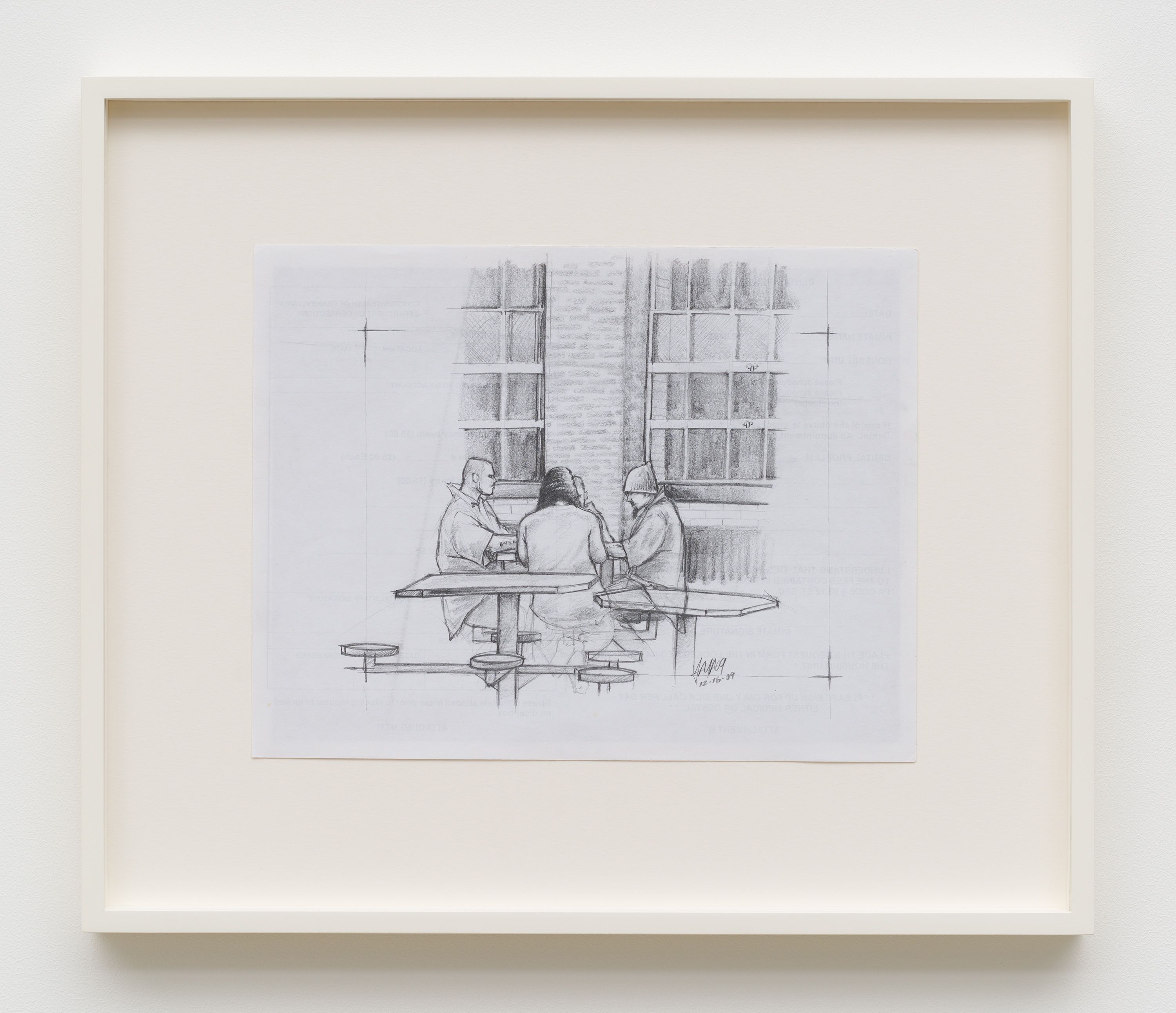

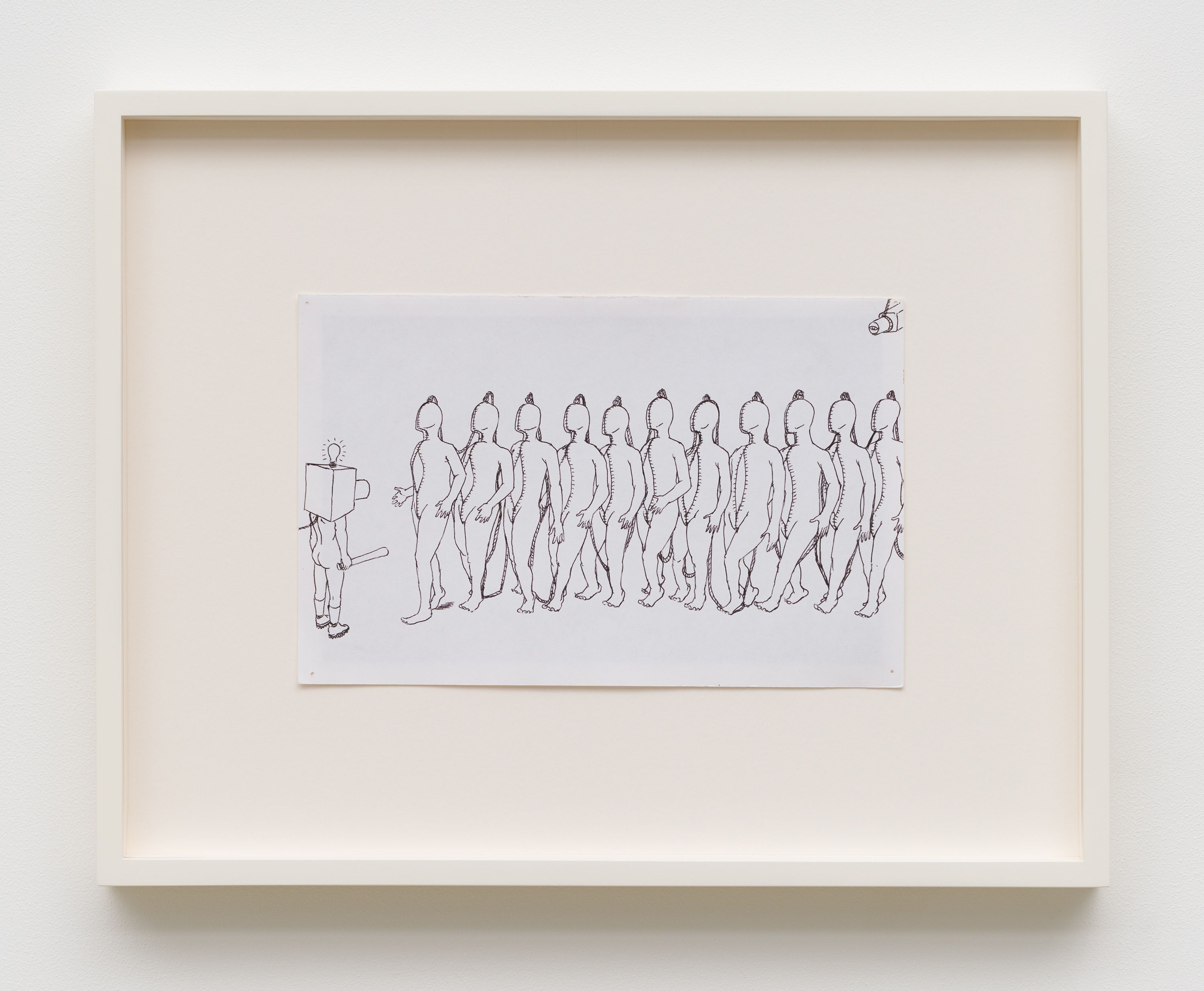

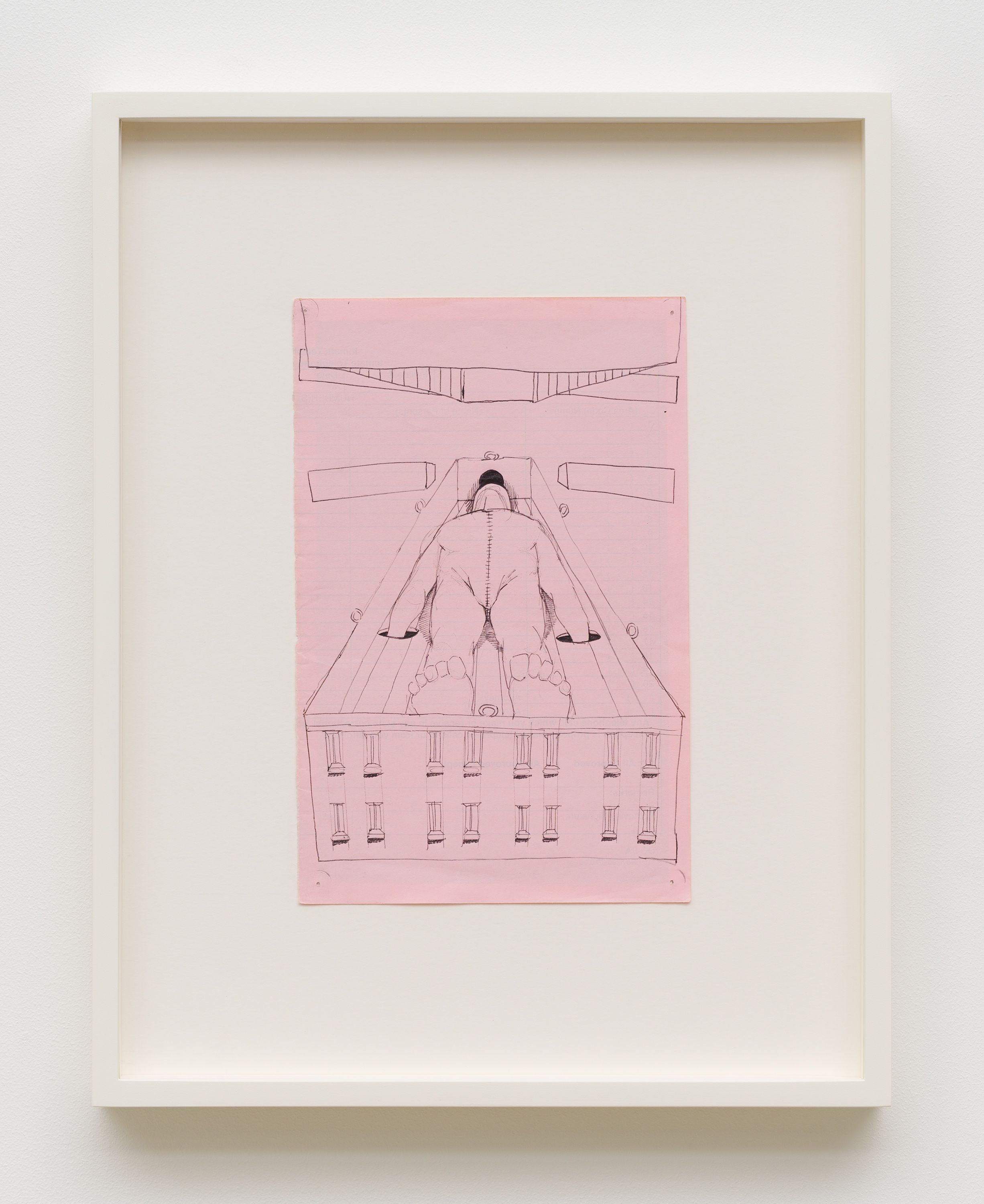

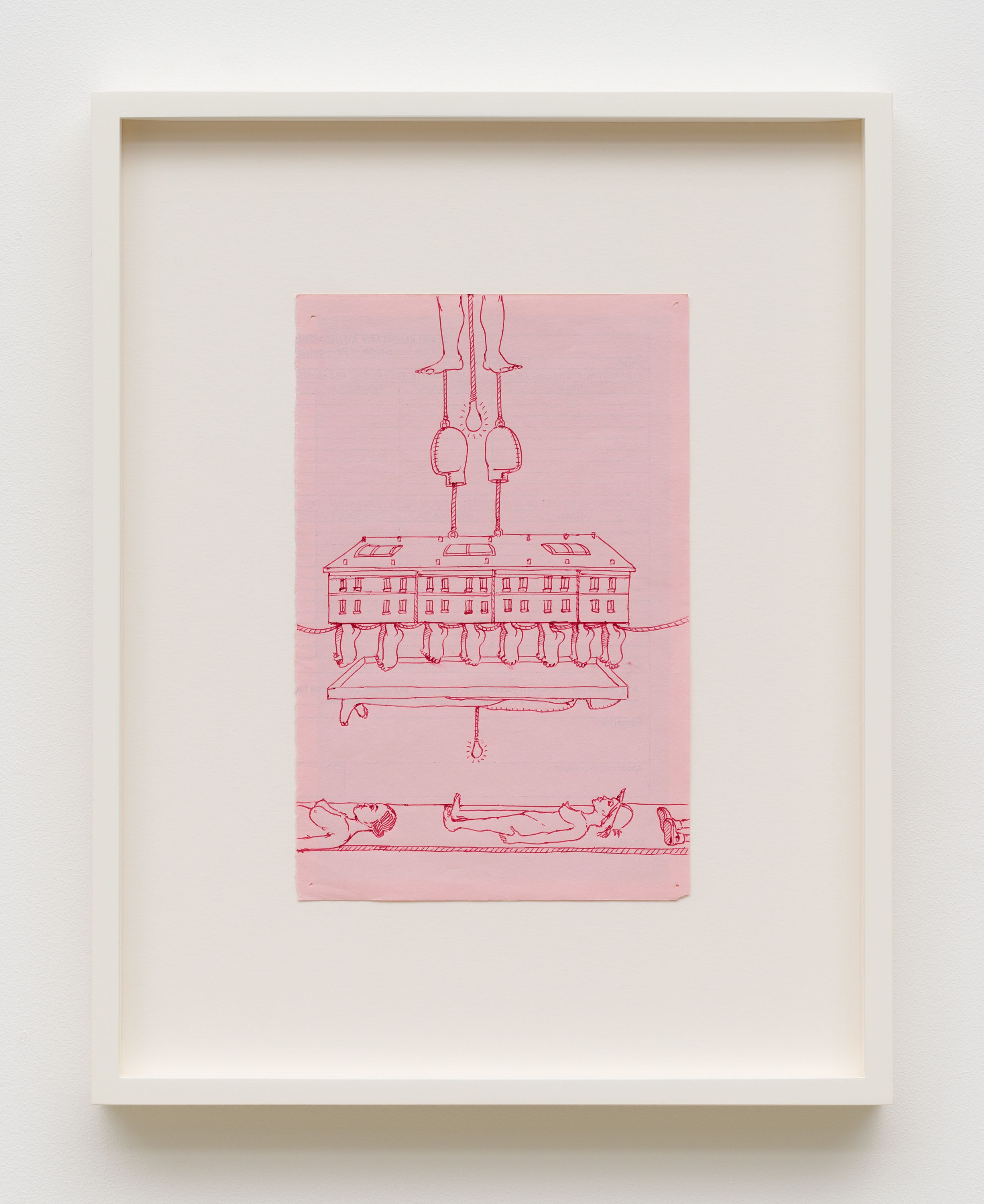

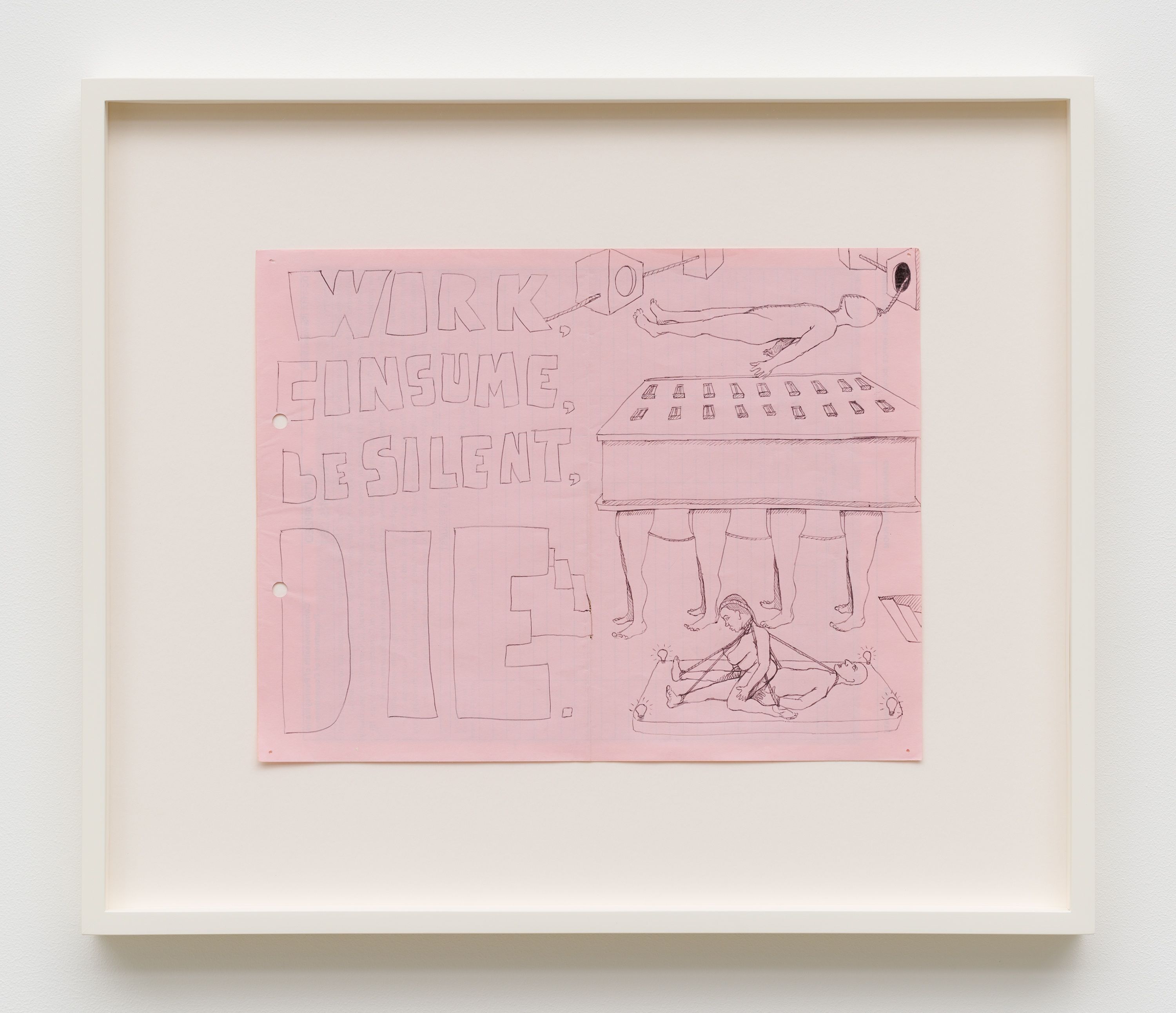

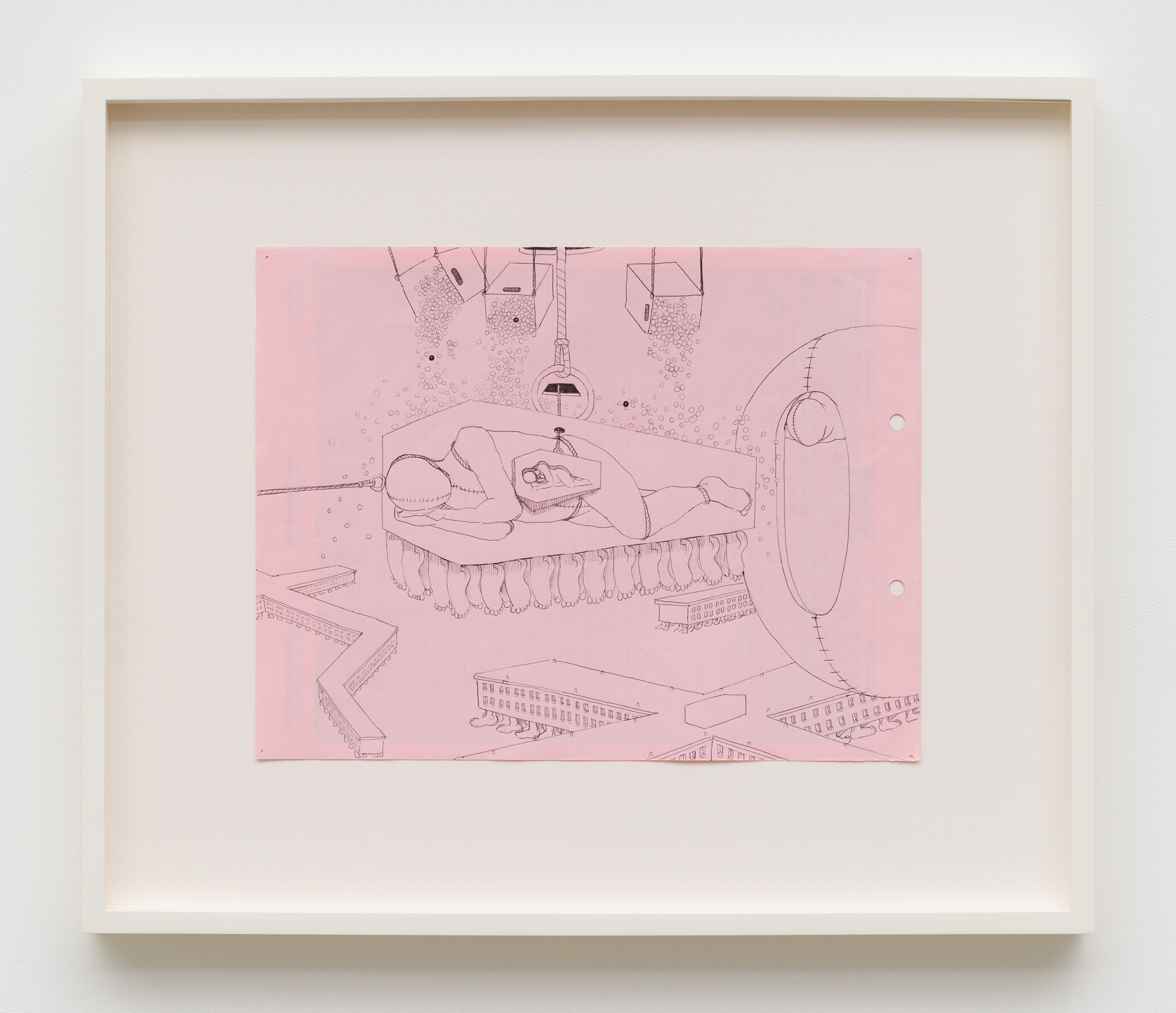

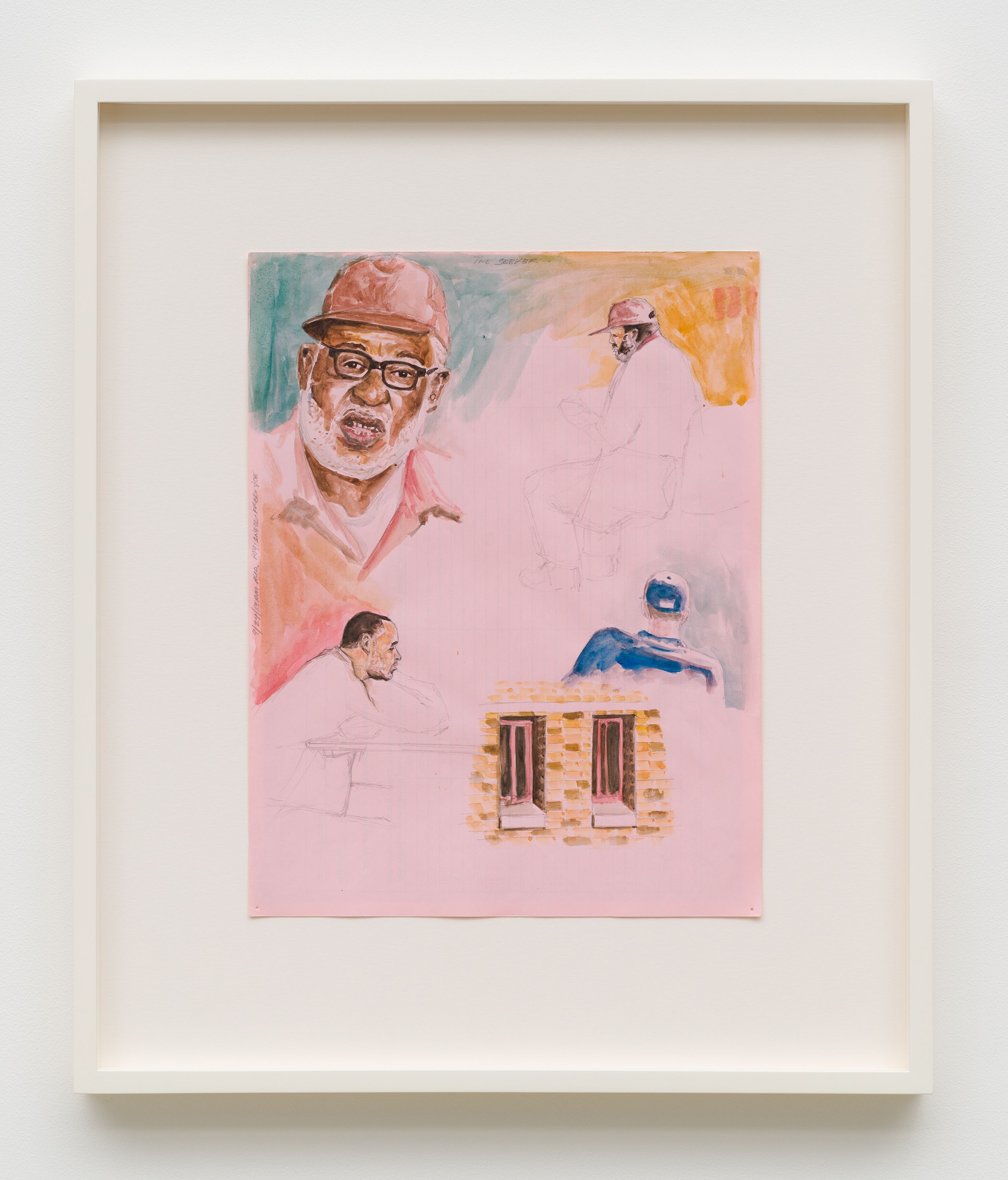

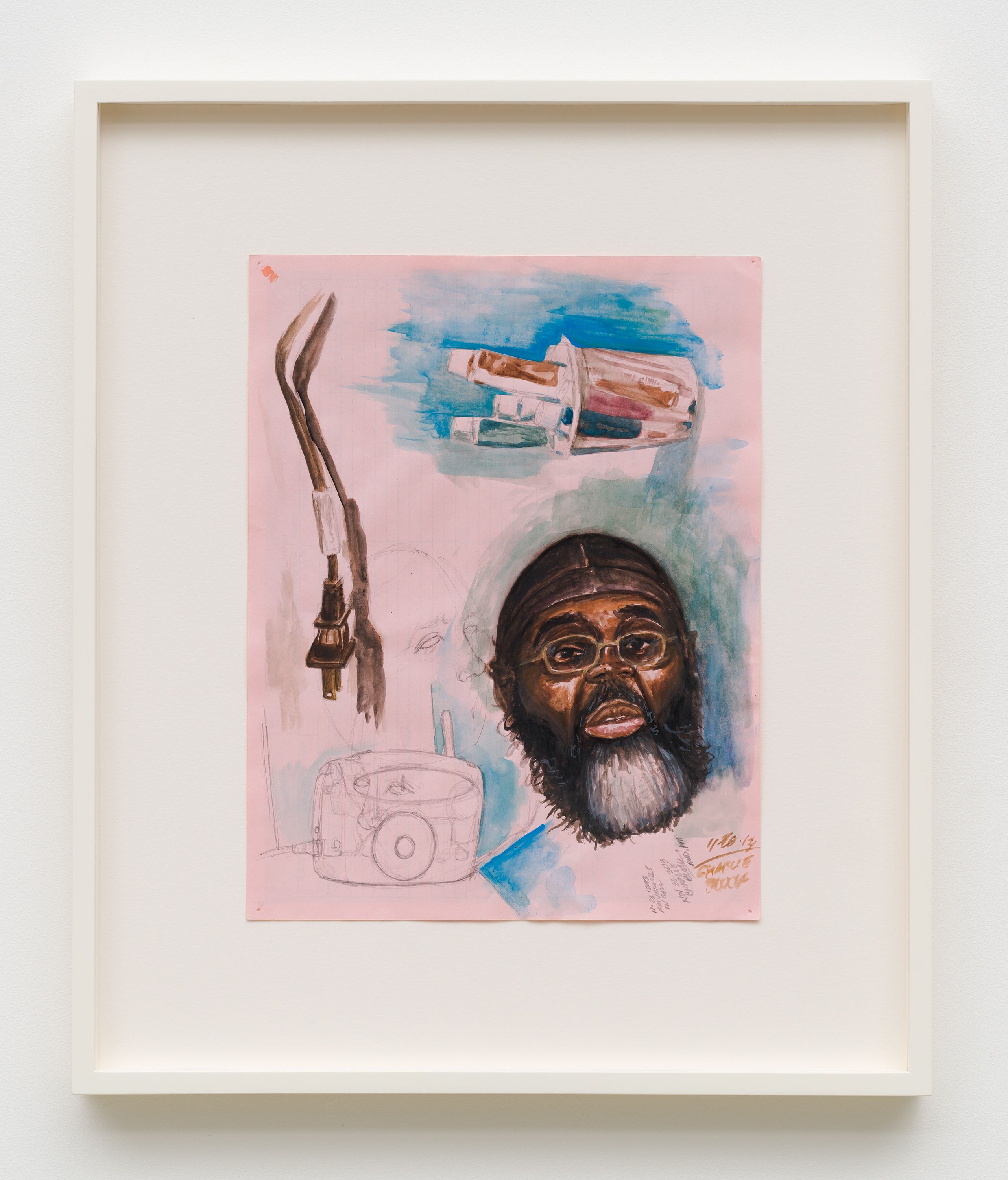

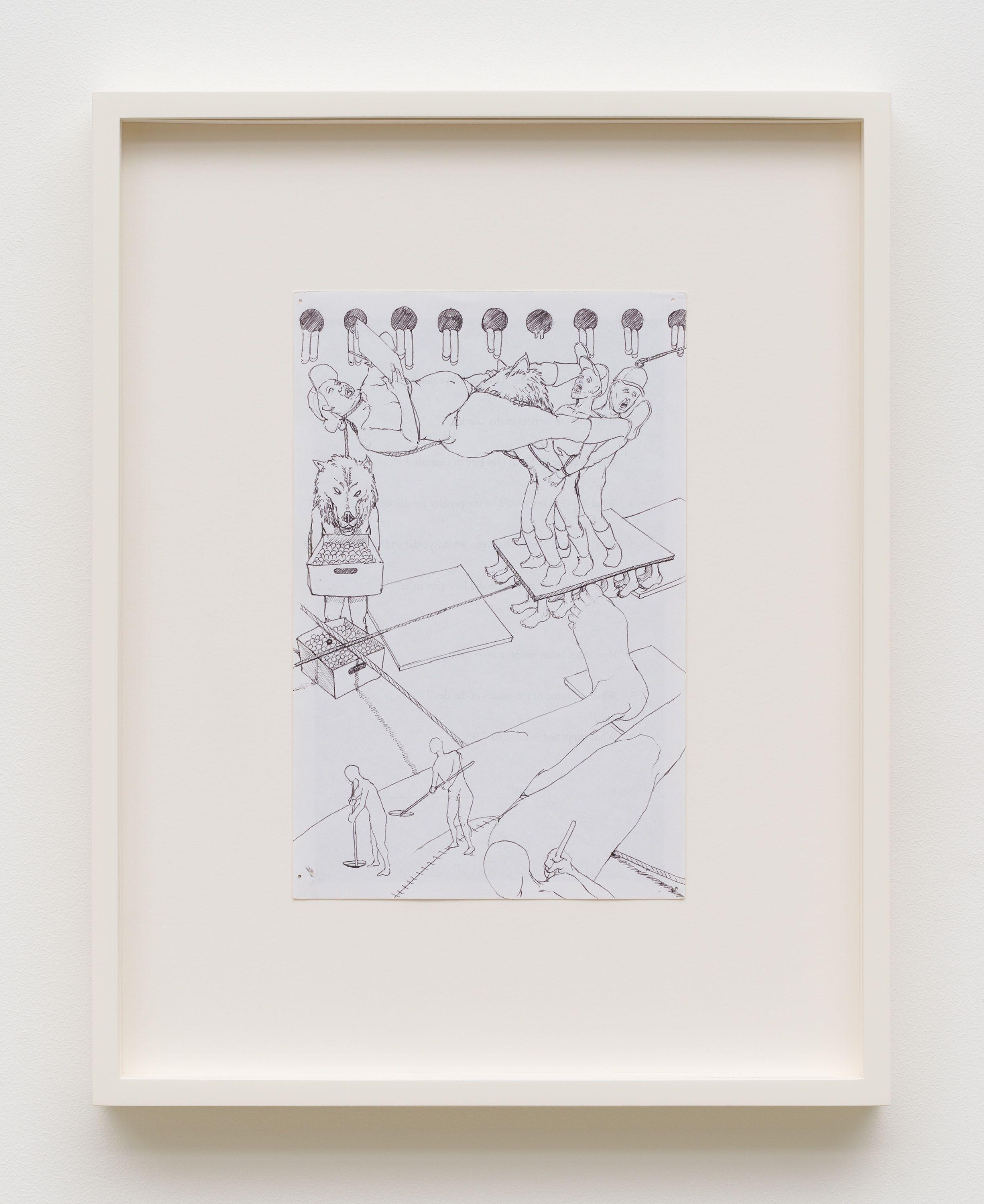

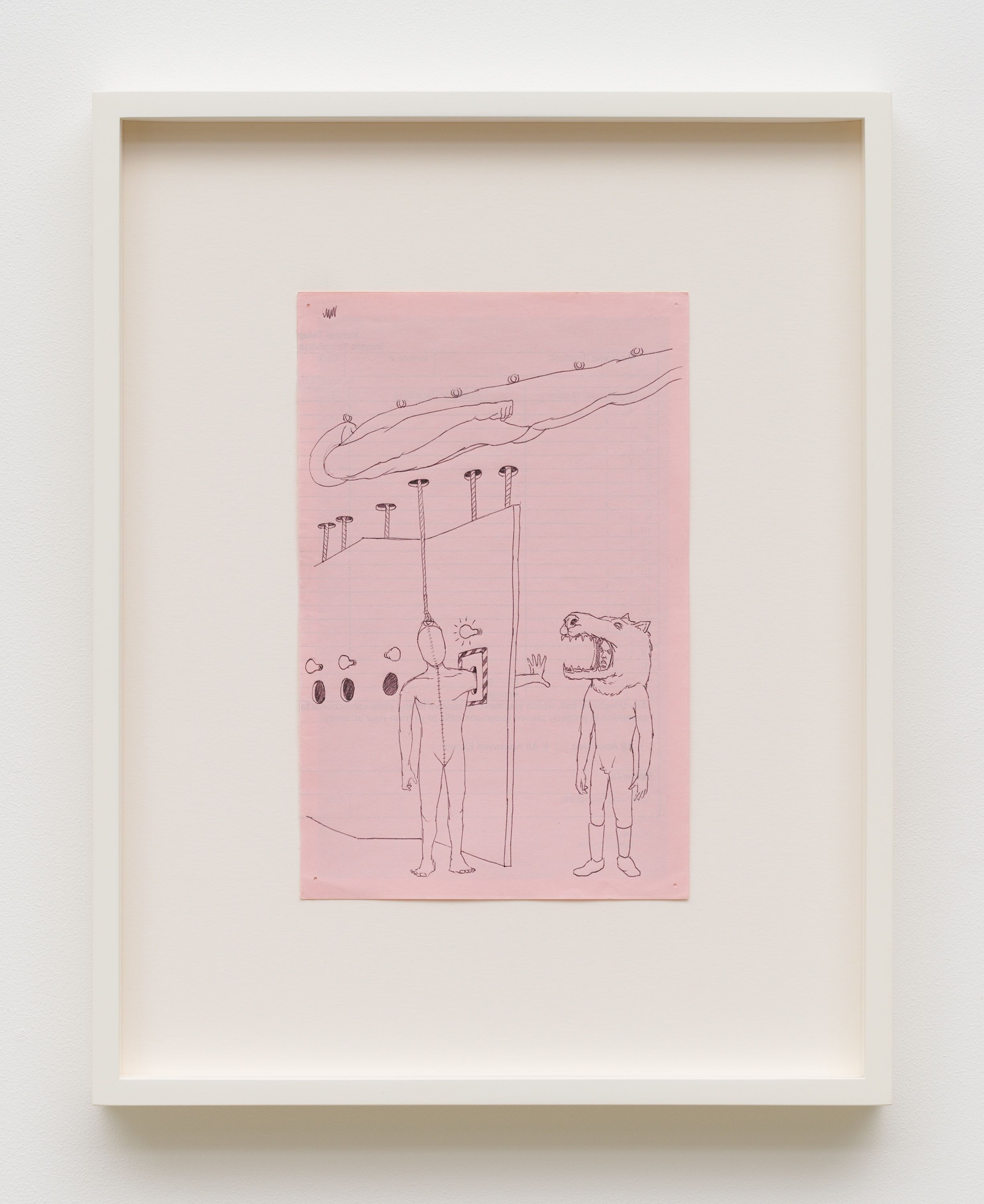

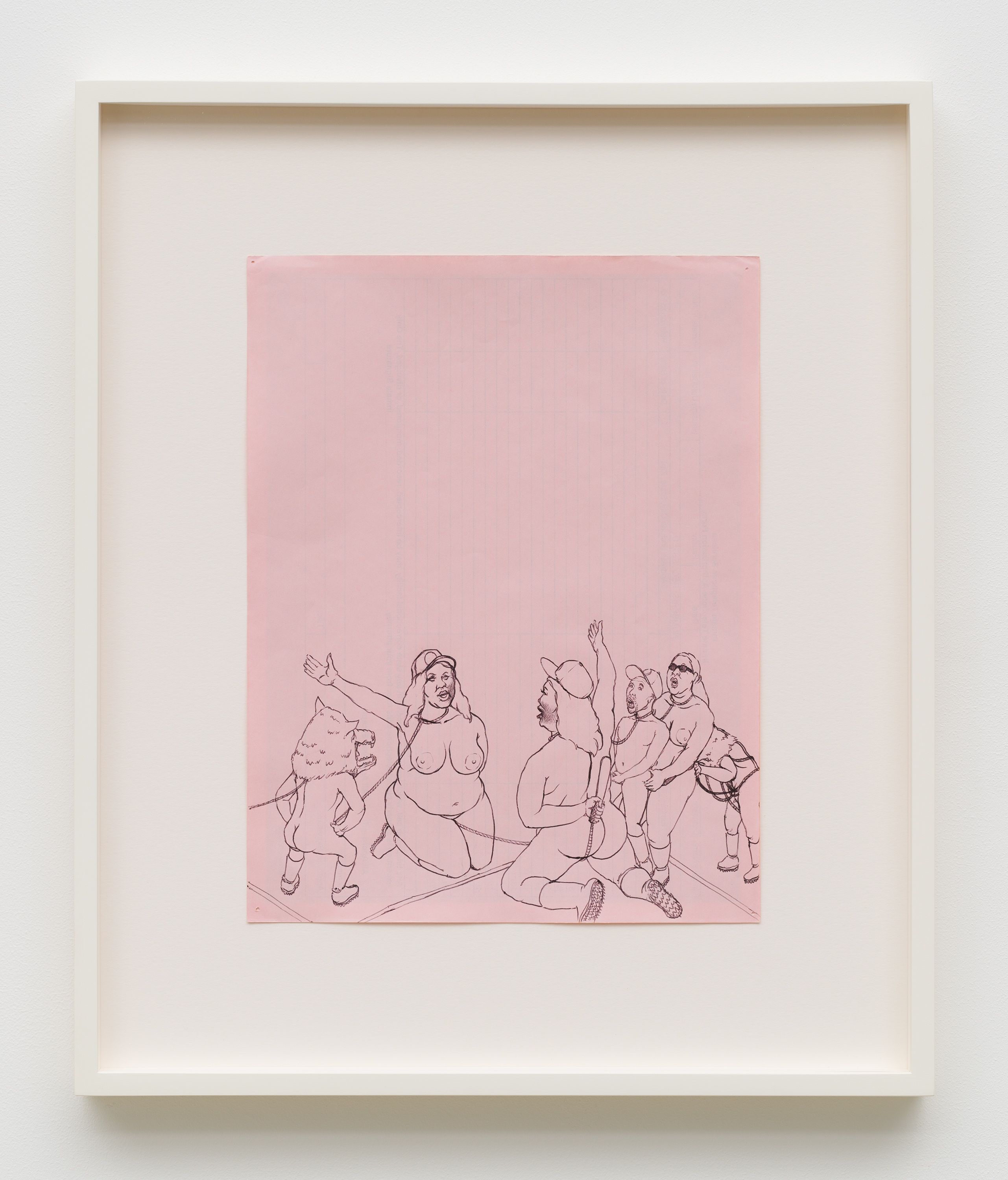

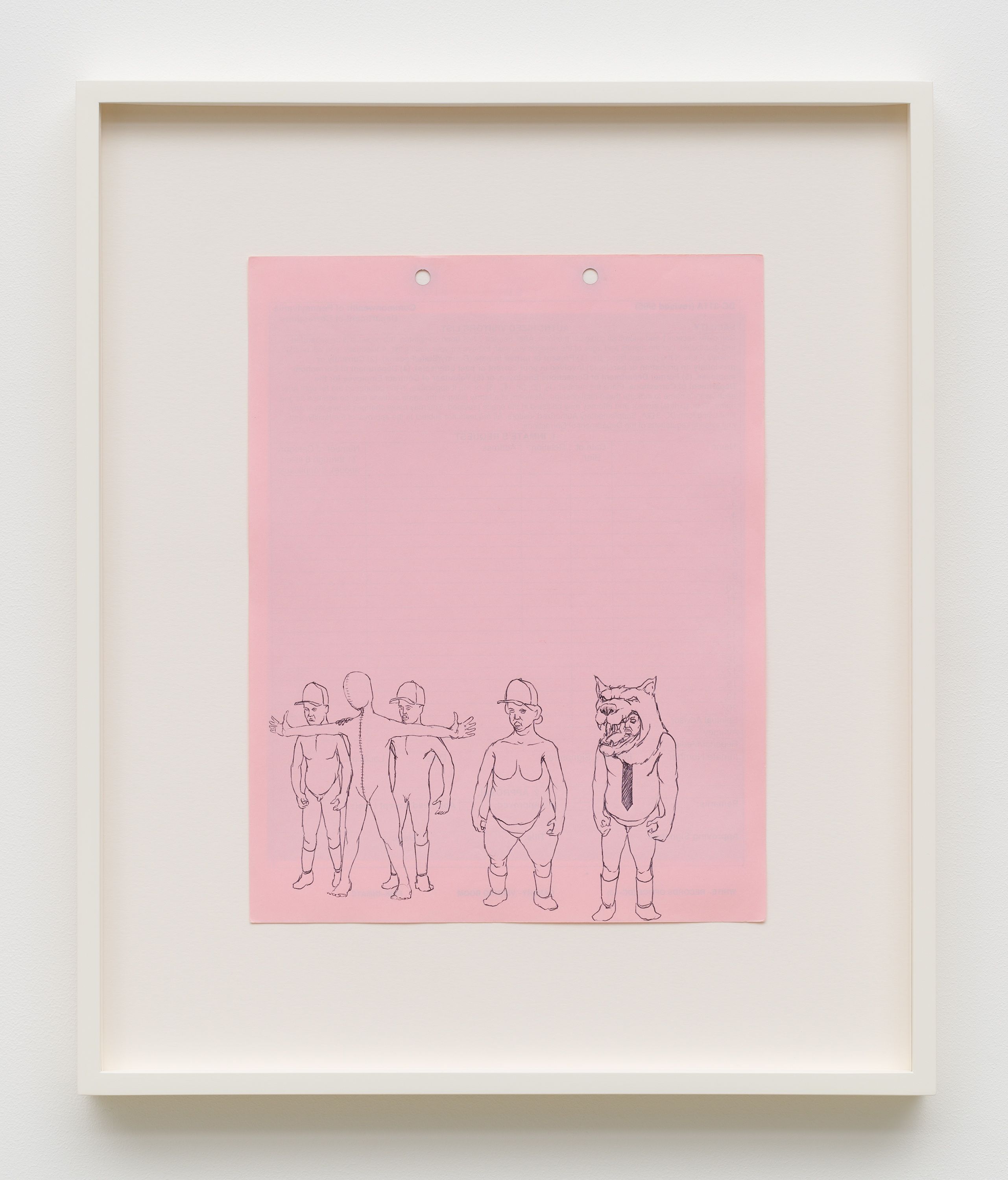

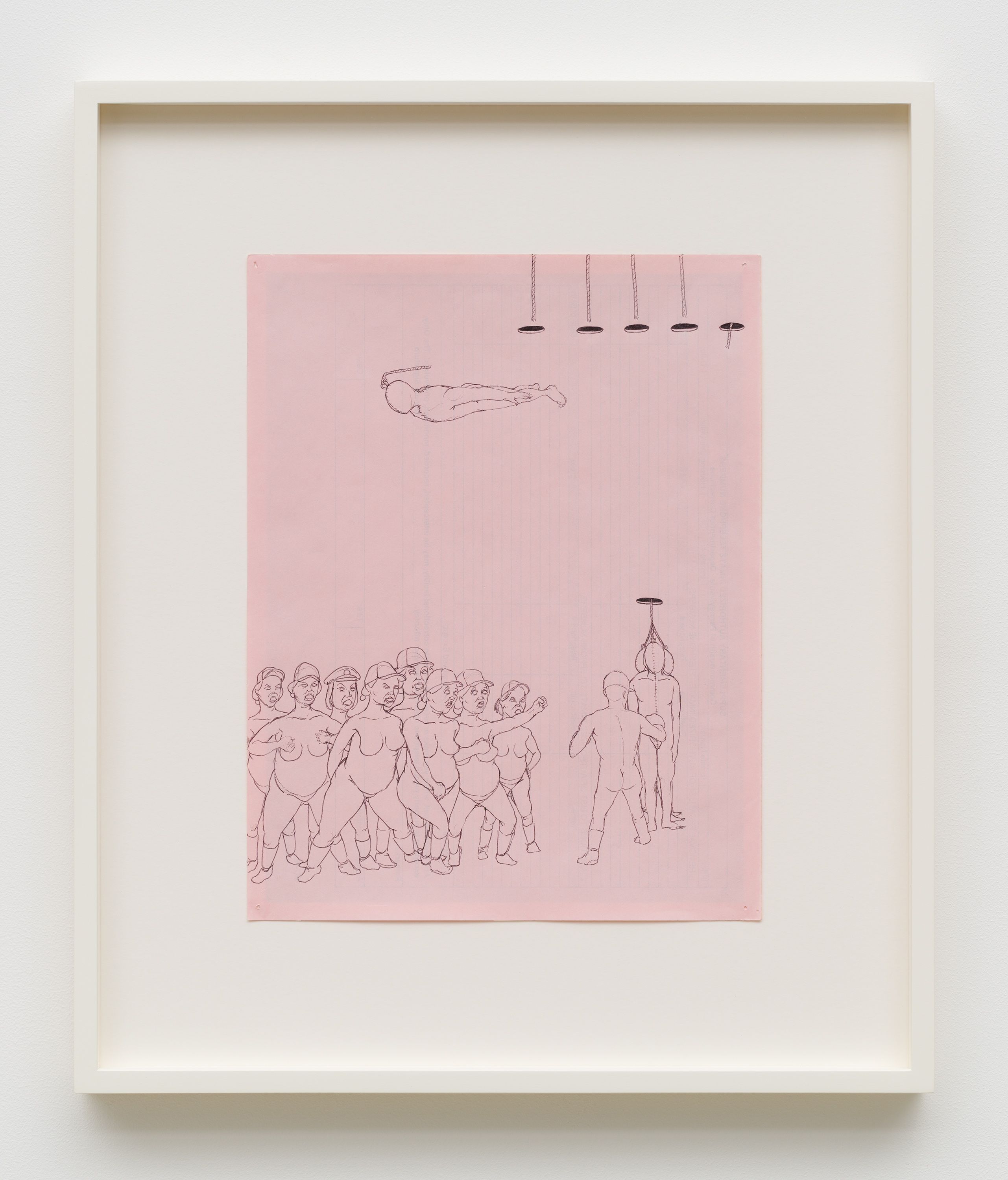

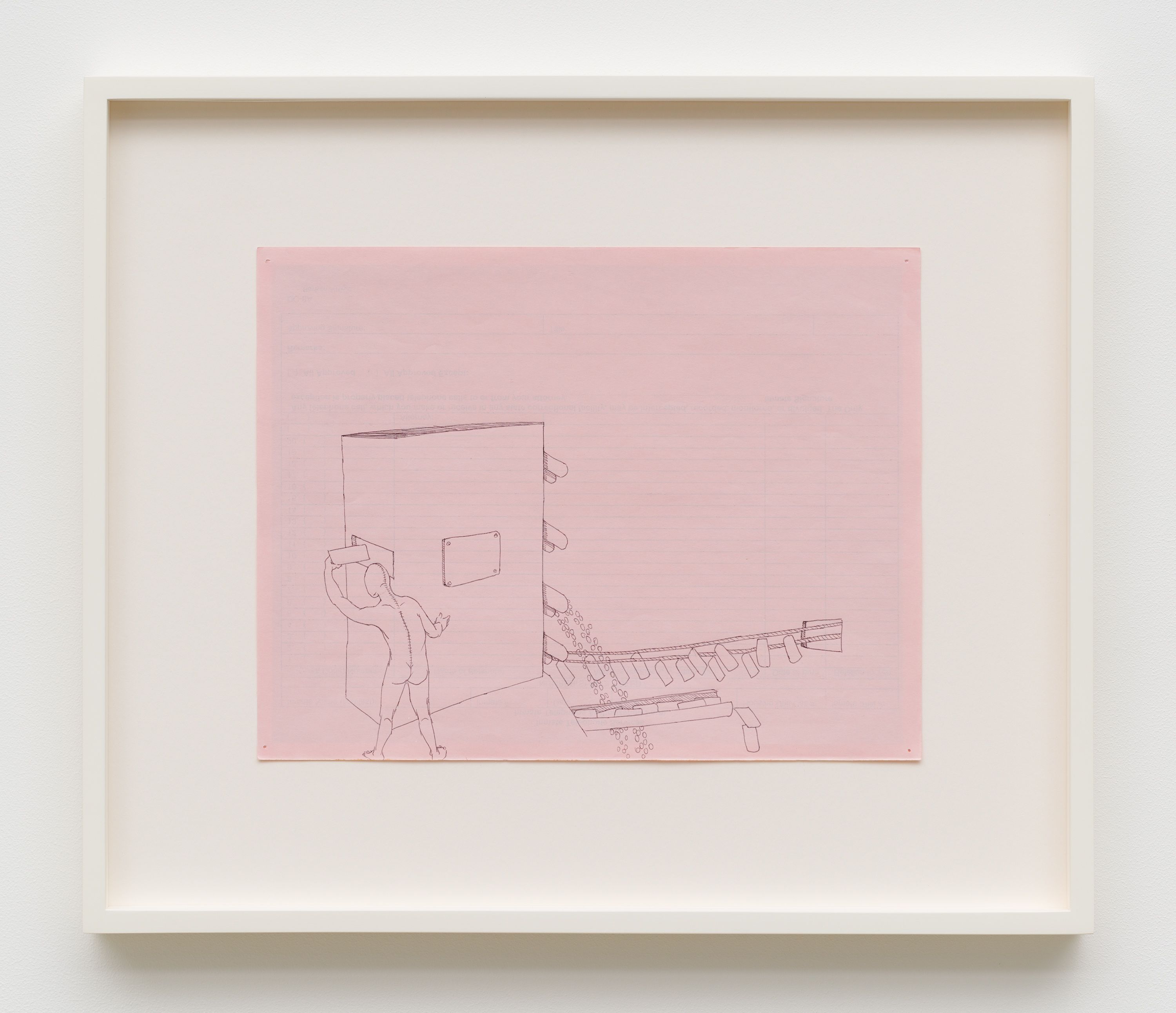

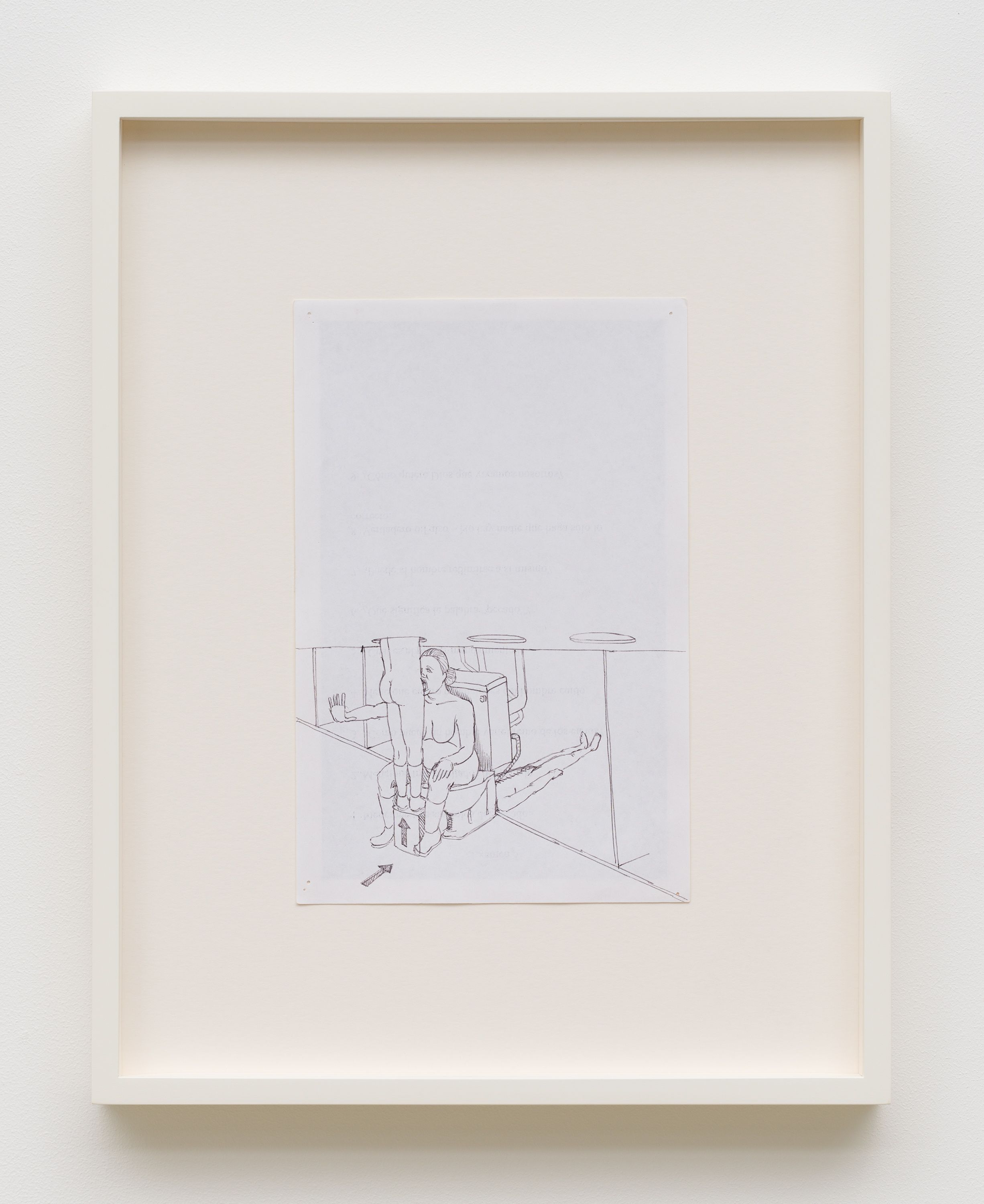

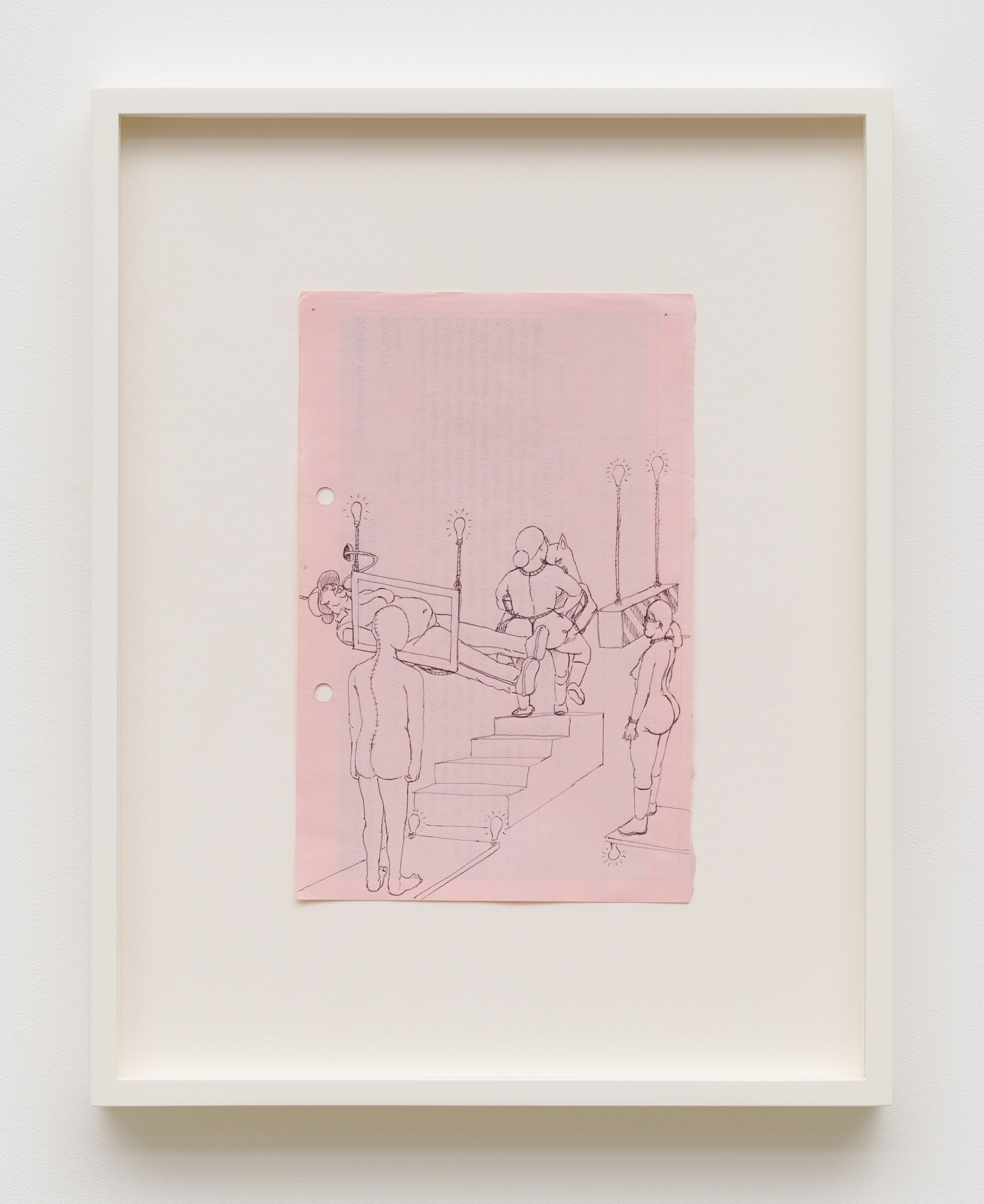

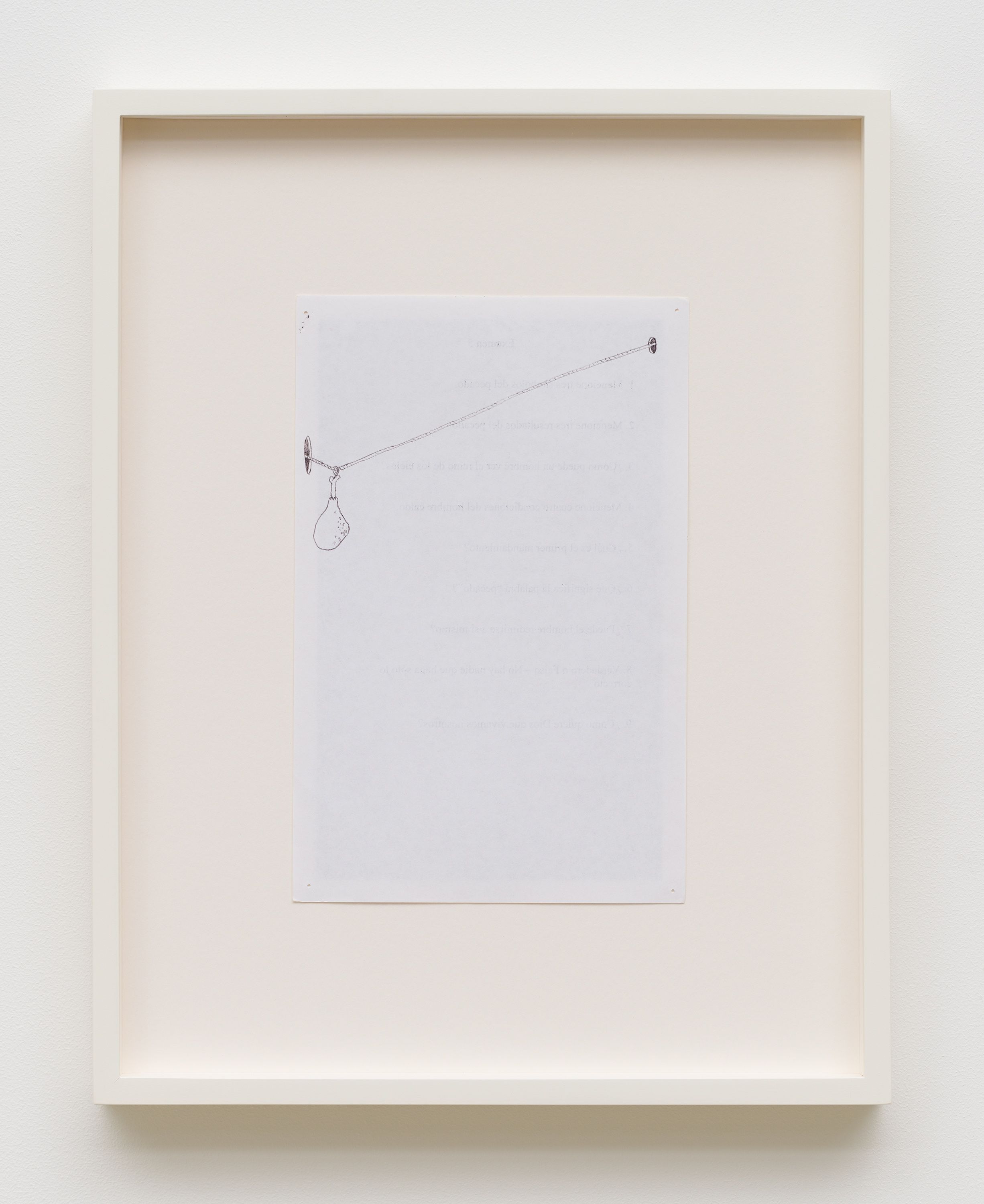

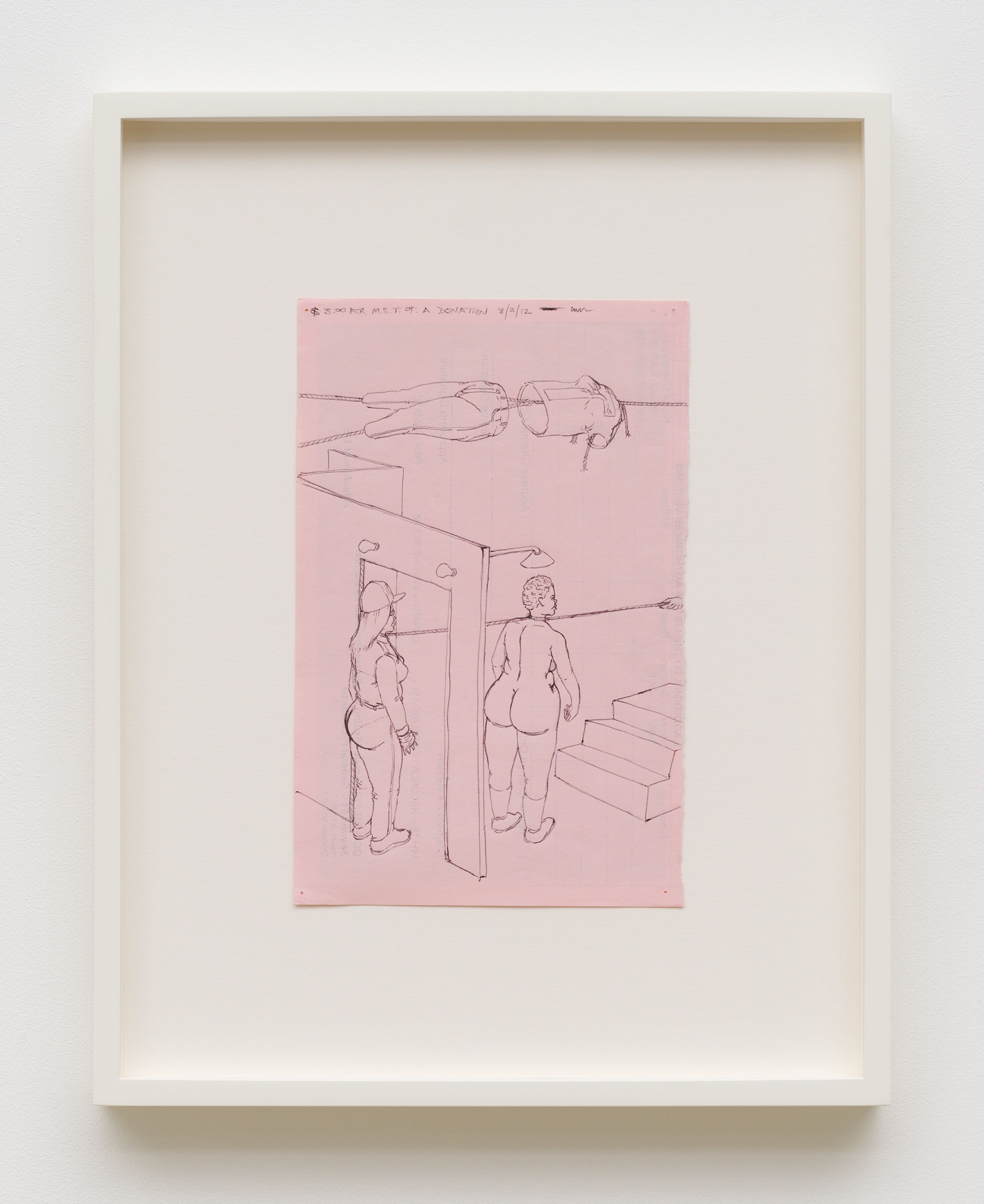

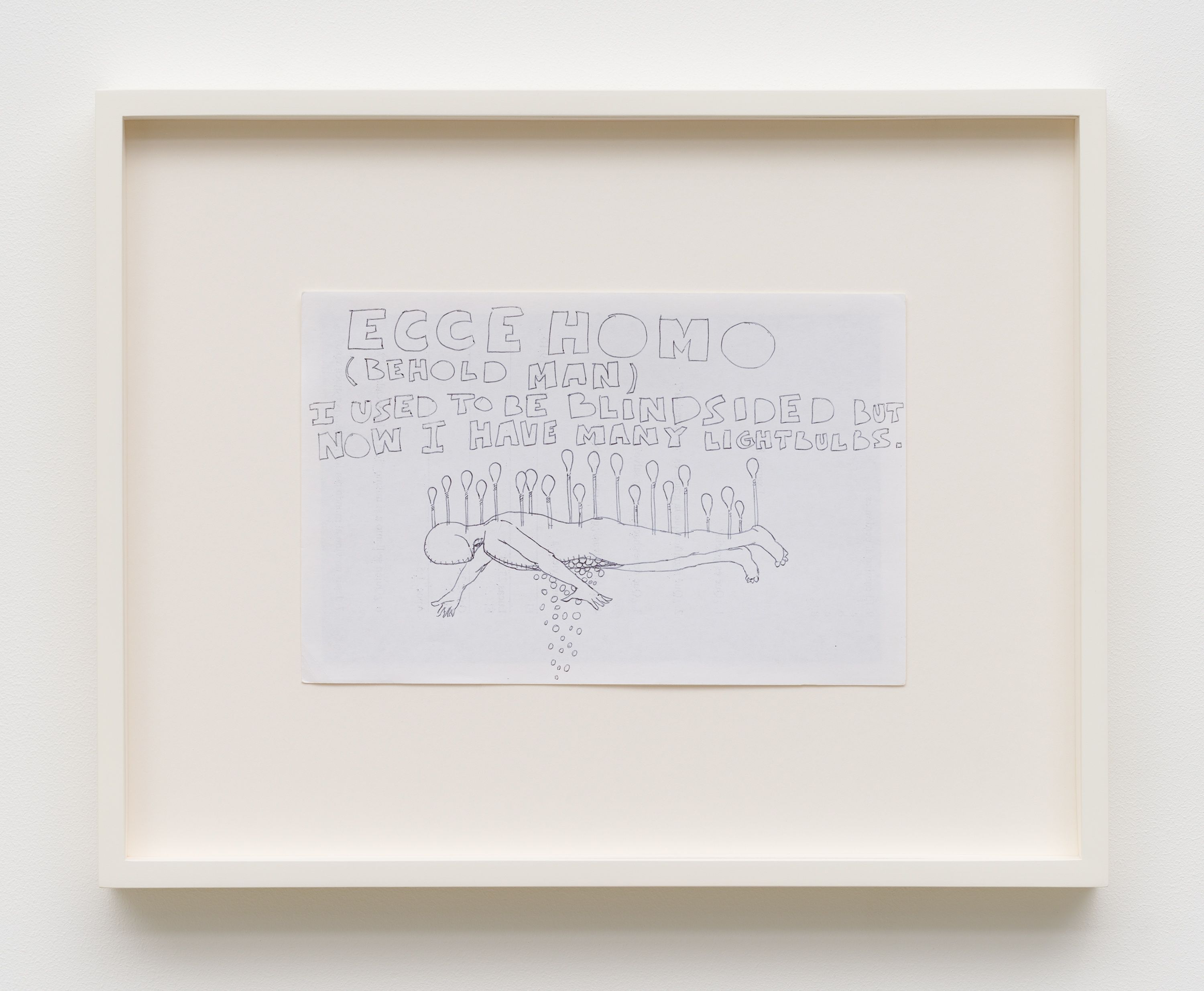

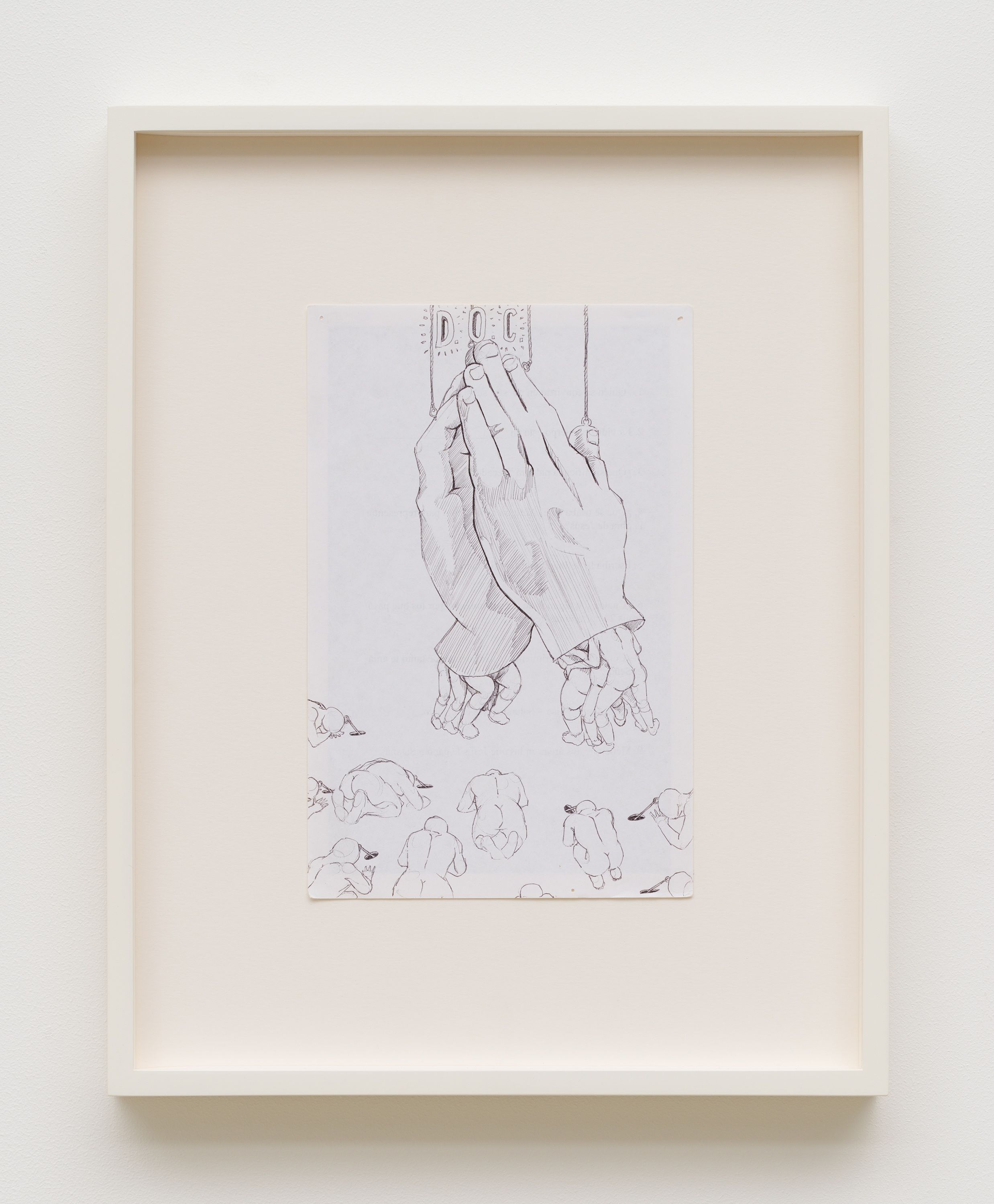

In 2008, Hough began to illustrate what he refers to as the economy of desire within the carceral system, on the very documents that represented the bureaucratic boundary between himself and his fellow inmates and their own humanity. Many of the documents on view list the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections in their headings. This resulted in the series Invisible Life which he worked on for over eight years. Invisible Life was exhibited in Rendering Justice at the African American Museum in Philadelphia curated by Jesse Krimes and Dr. Nicole Fleetwood’s field-breaking exhibition Marking Time: Art in the Age of Incarceration which debuted its multi venue exhibition at MoMA PS1 in 2020. The series was also exhibited in Hough’s first solo show at the gallery in 2021, as well as in Crossroads: Carnegie Museum of Art’s Collection, 1945 to Now currently on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art. In Grievance for the first time, the works are installed in a narrative fashion and include a display that allows viewers to see both the front and the backside of the Inmate Grievance Forms. Starting from the north side of the gallery, the drawings illustrate an entry, consumption and ultimate submission to Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections in the style of what Hough refers to as a “futuristic slave plantation.” The first work displays men in correctional uniforms that walk through a portal to become faceless, clothingless bodies on the other end. From here, the figure attempts to escape but fails, and is attached to an intricate rope and pulley system that connects him to other prisoners and the architecture around them ensuring their captivity. The series is broken up with tender watercolors, studies of his surroundings that bear witness to the people Hough spent his life with while incarcerated. As the figures navigate assembly lines, female prison guards enter into the narrative, often depicted with voluptuous bodies experiencing sexual encounters that oscillate between fantasy, humiliation and violence. Towards the end, the figure is found levitating in a cell, one drawing reads “ECCE HOMO (BEHOLD MAN) I USED TO BE BLINDSIDED BUT NOW I HAVE MANY LIGHTBULBS.”

_________________________________________

[1] In 2012 two cases were brought before the Supreme Court arguing that mandatory life sentences without the possibility of parole for juveniles violated the 8th amendment. Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative argued in these cases that children are constitutionally different from adults in their levels of culpability – and won with a 5 to 4 decision.

paper, colored pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, colored pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, colored pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, colored pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, colored pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, colored pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

5.5 x 8.5 in

14 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

5.5 x 8.5 in

14 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

5.5 x 8.5 in

14 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

5.5 x 8.5 in

14 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

4 x 9.5 in

10.5 x 24 cm

paper, ink, pencil

4 x 9.5 in

10.5 x 24 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

5.5 x 8.5 in

14 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 11 in

21.5 x 28 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14 cm

paper, ink, pencil

5.5 x 8.5 in

14 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

5.5 x 8.5 in

14 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14cm

paper, ink, pencil

8.5 x 5.5 in

21.5 x 14cm

paper, ink, pencil

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm

paper, ink, pencil, watercolor

11 x 8.5 in

28 x 21.5 cm