Filthy Dreams

The Brooklyn Rail

The New York Times

Cultured

In White Meat, her third solo show with JTT, KING COBRA (documented as Doreen Lynette Garner) uses the tactics of a joker pulling the cloak off of a maniacal king to shatter the collective restraint in scrutinizing whiteness. In this exhibition, whiteness recurs as a material throughout Cobra’s sculptures, and not as its usual stand-in for the vulnerability of the corporeal body as it so commonly has been used throughout art history. Rather, the depictions of whiteness on view here account for its entanglement with colonial violence, consumption, appropriation, performativity, and the construction of assimilation models. Each object on view in the show refers to these as conditions and their implications for whiteness.

Cobra’s ongoing unflinching engagement with flesh has long been inspired by art practices that have viscerally depicted the body, a central tenet of abjection. Abject artists of the 1990s used body parts, skin and blood to probe the parameters of what was considered taboo without restraint. But what does it mean that so many of those bodies were white? Echoing the title of a 2018 essay by Miguel Gutierrez about race, abstraction, and dance, Cobra posits: does abjection belong to white people?[1] As the work in the exhibition suggests, perhaps the abject white body has been so effective in eliciting strong feelings of revulsion because whiteness is so inextricably tied to humanity, itself a function of racism. Using whiteness as her material, Cobra opens up the conversation around abjection and forces us to reckon with whiteness as a specific subject position, rather than exempt it as neutral.

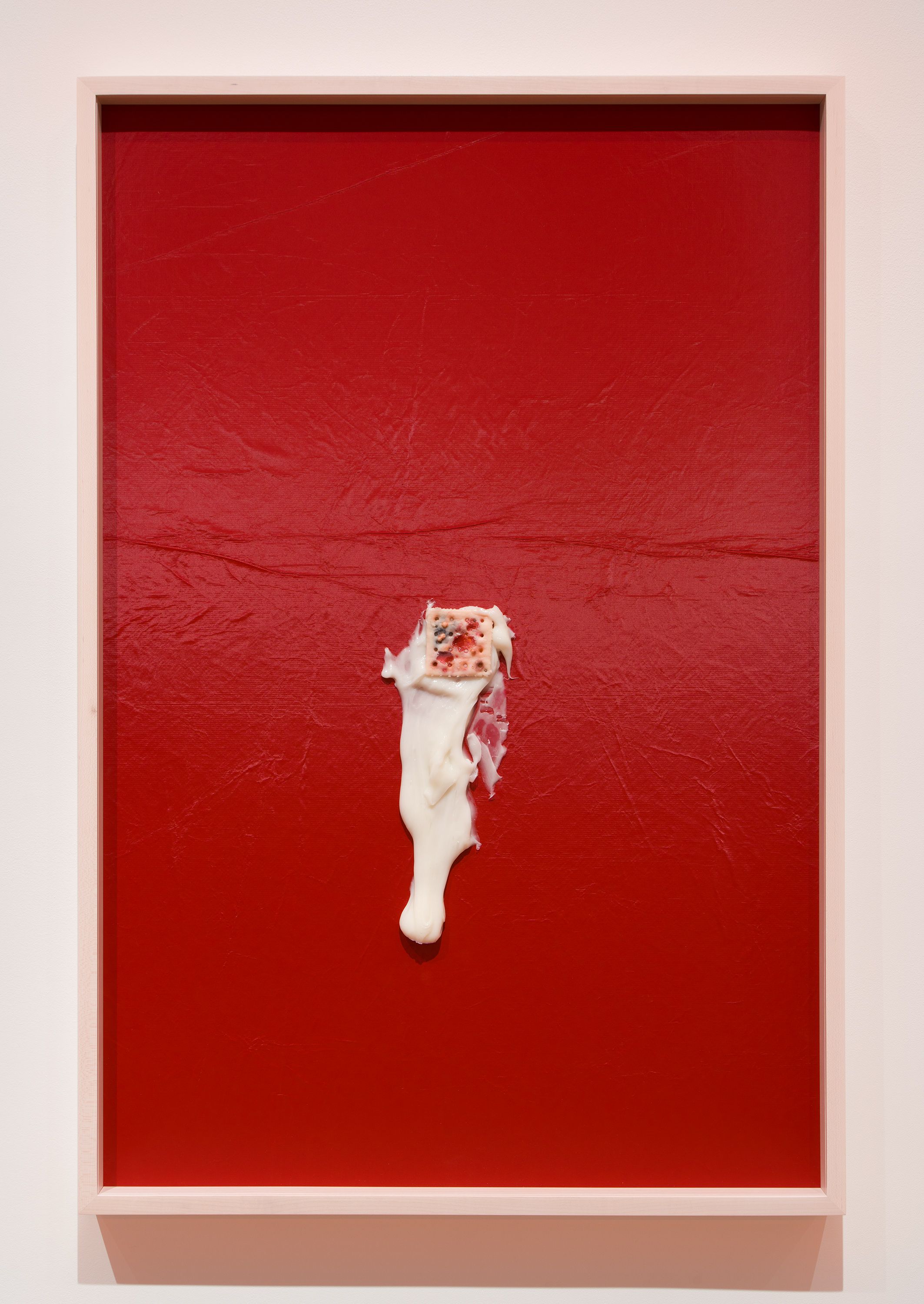

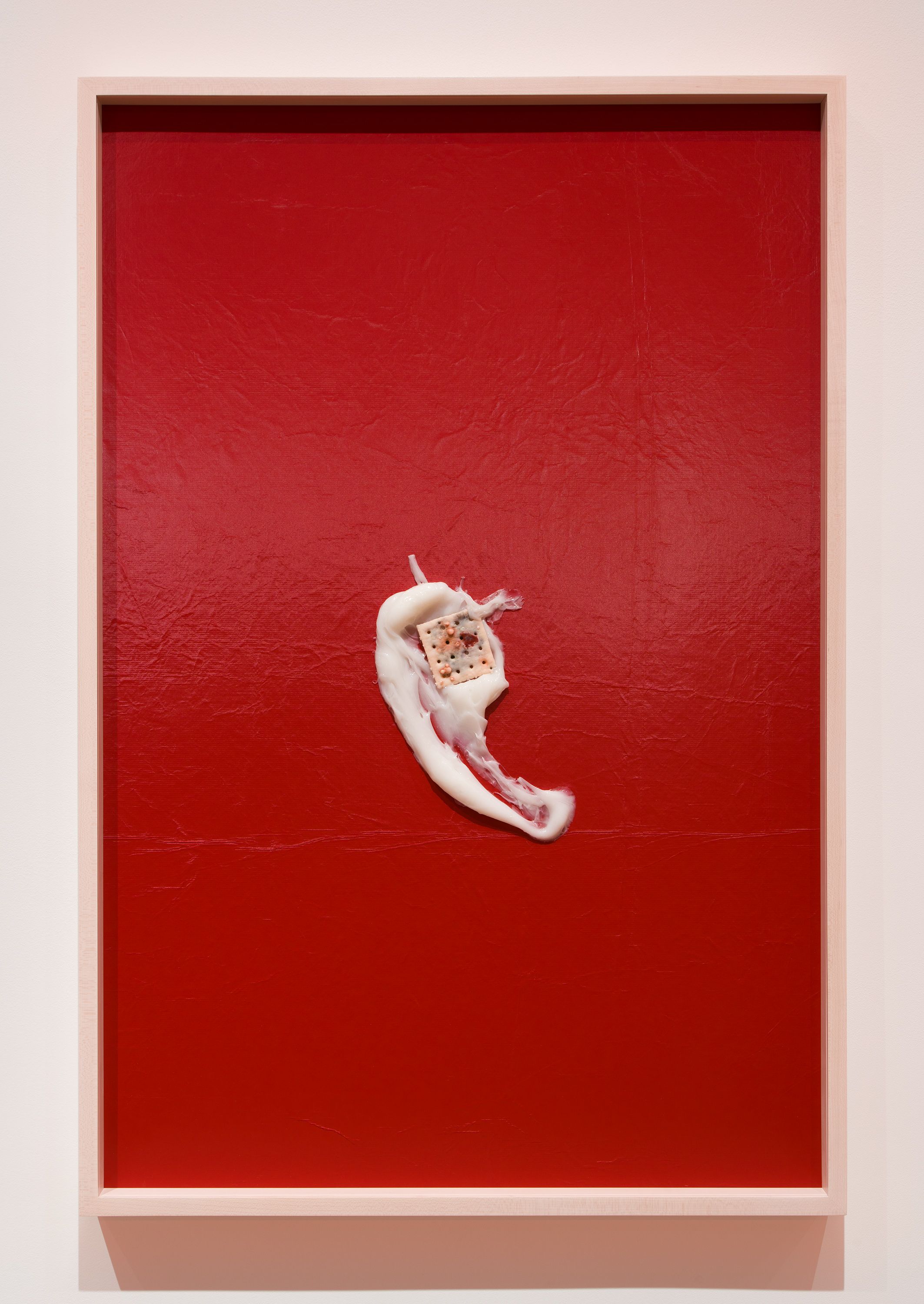

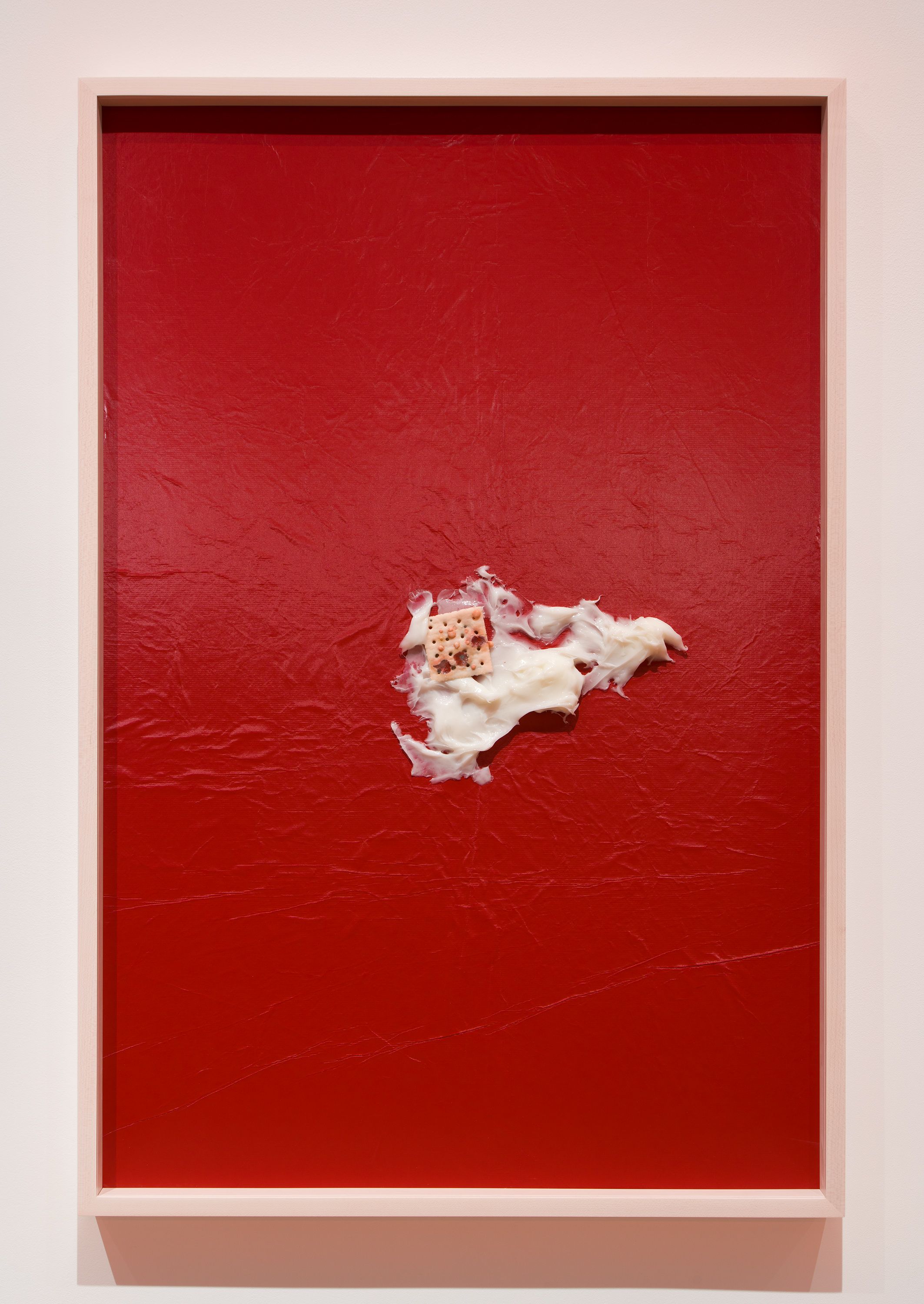

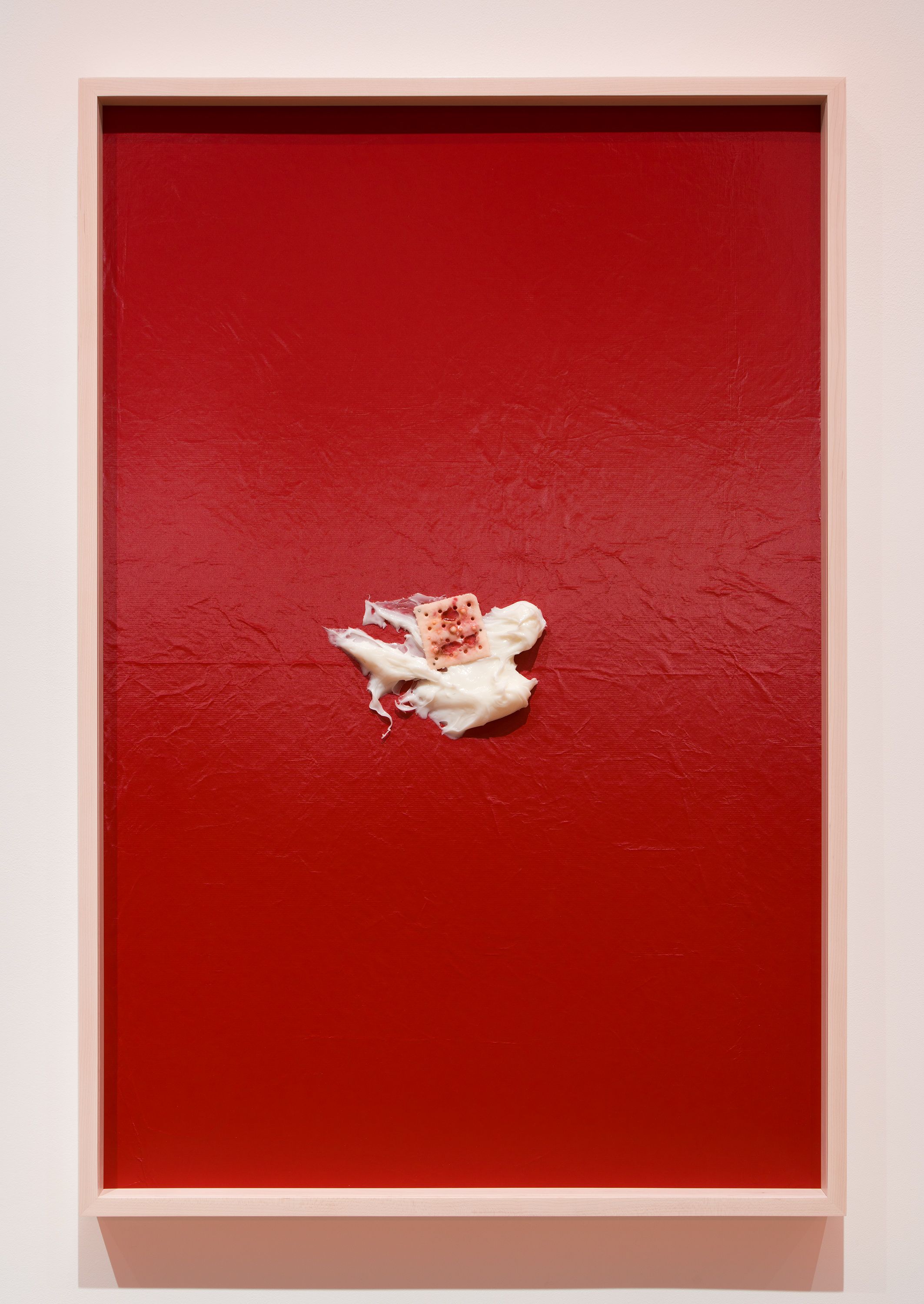

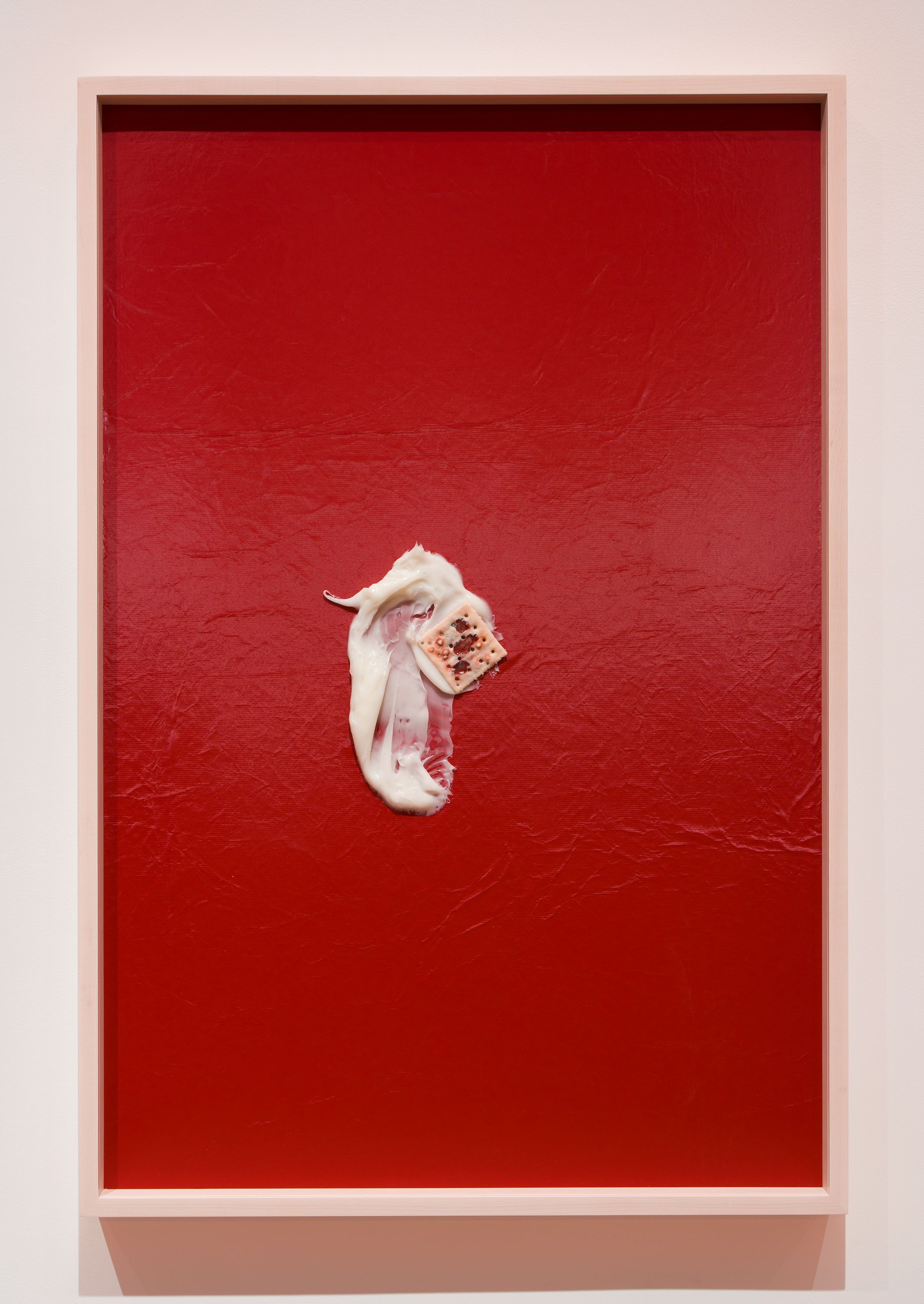

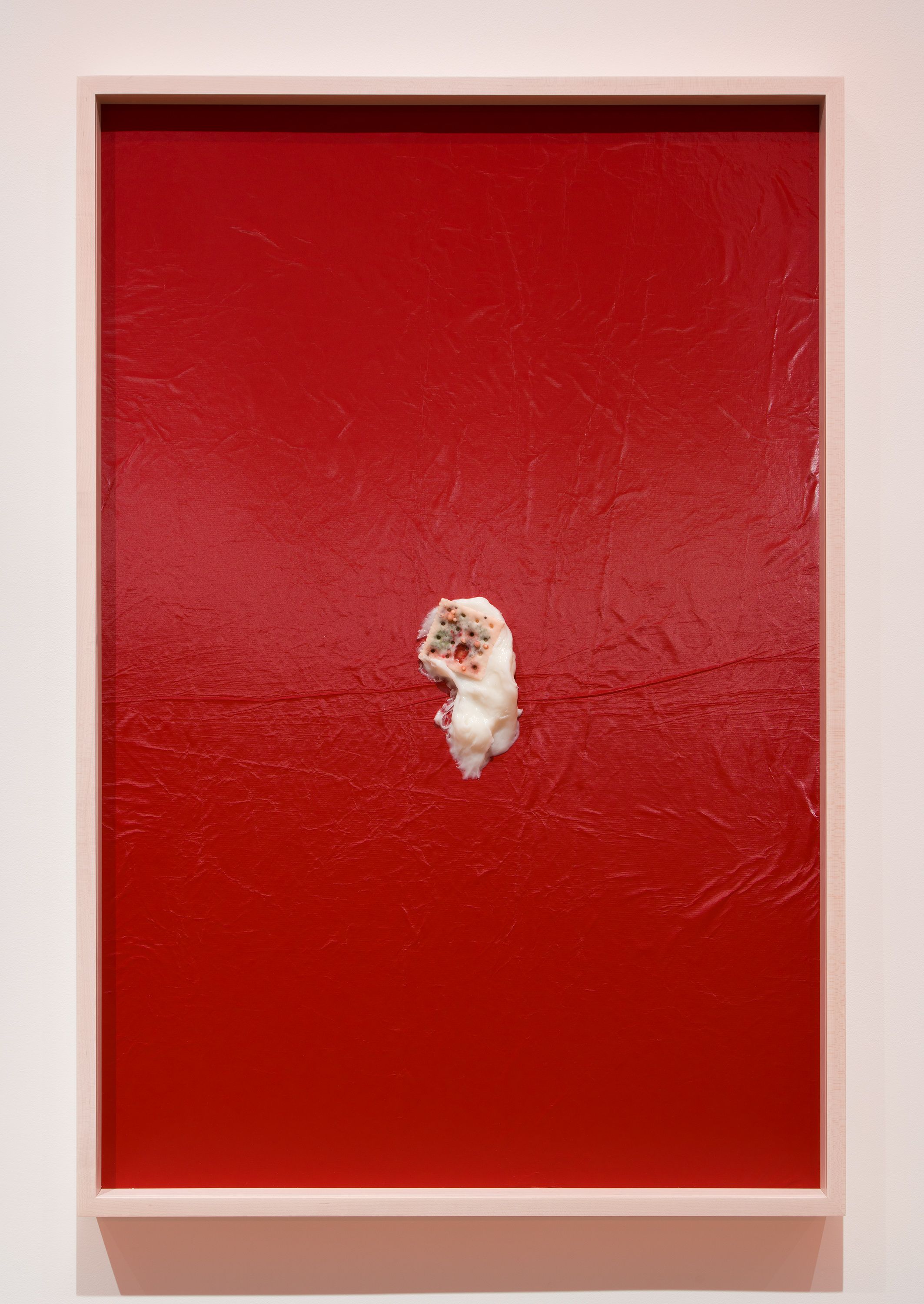

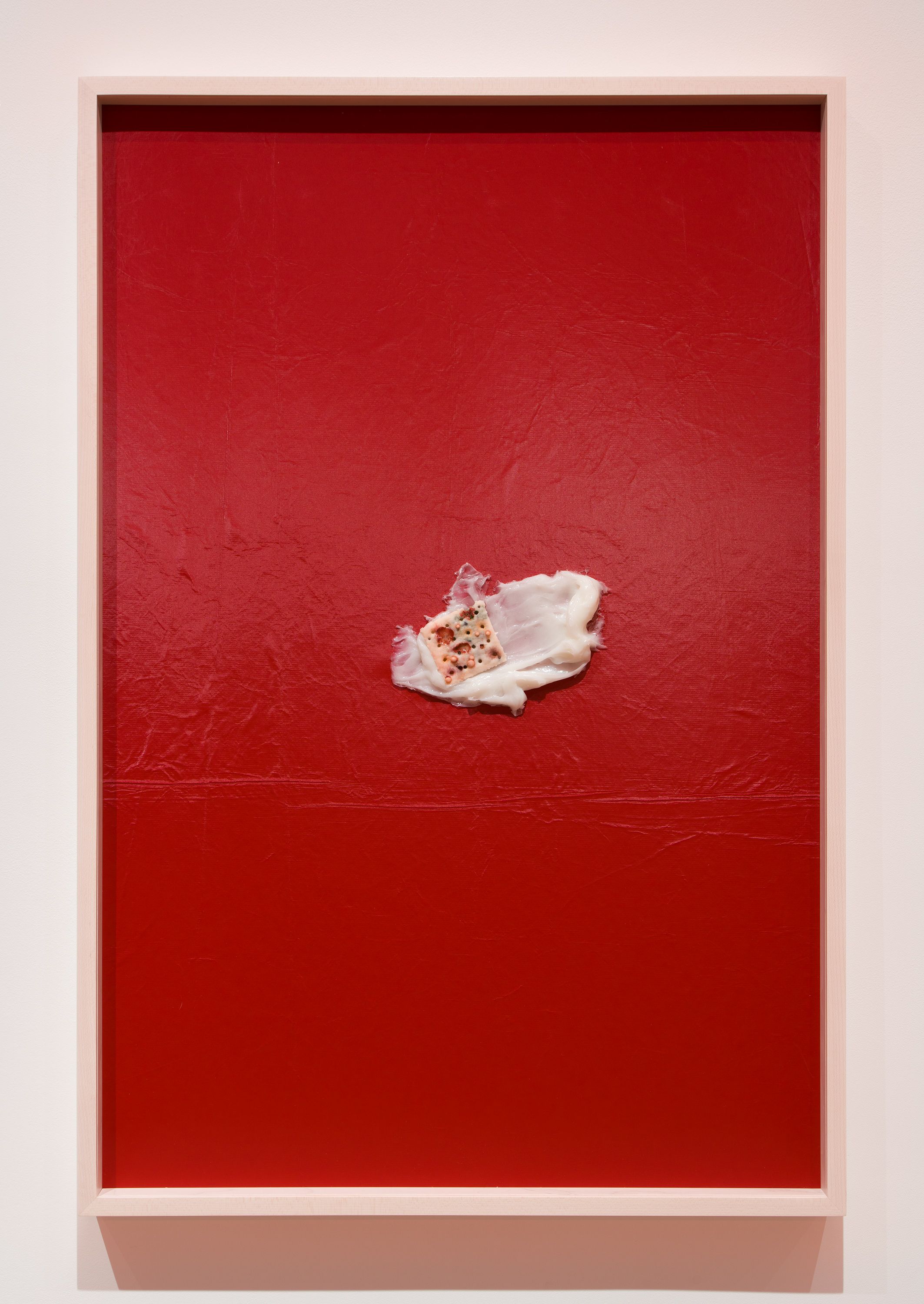

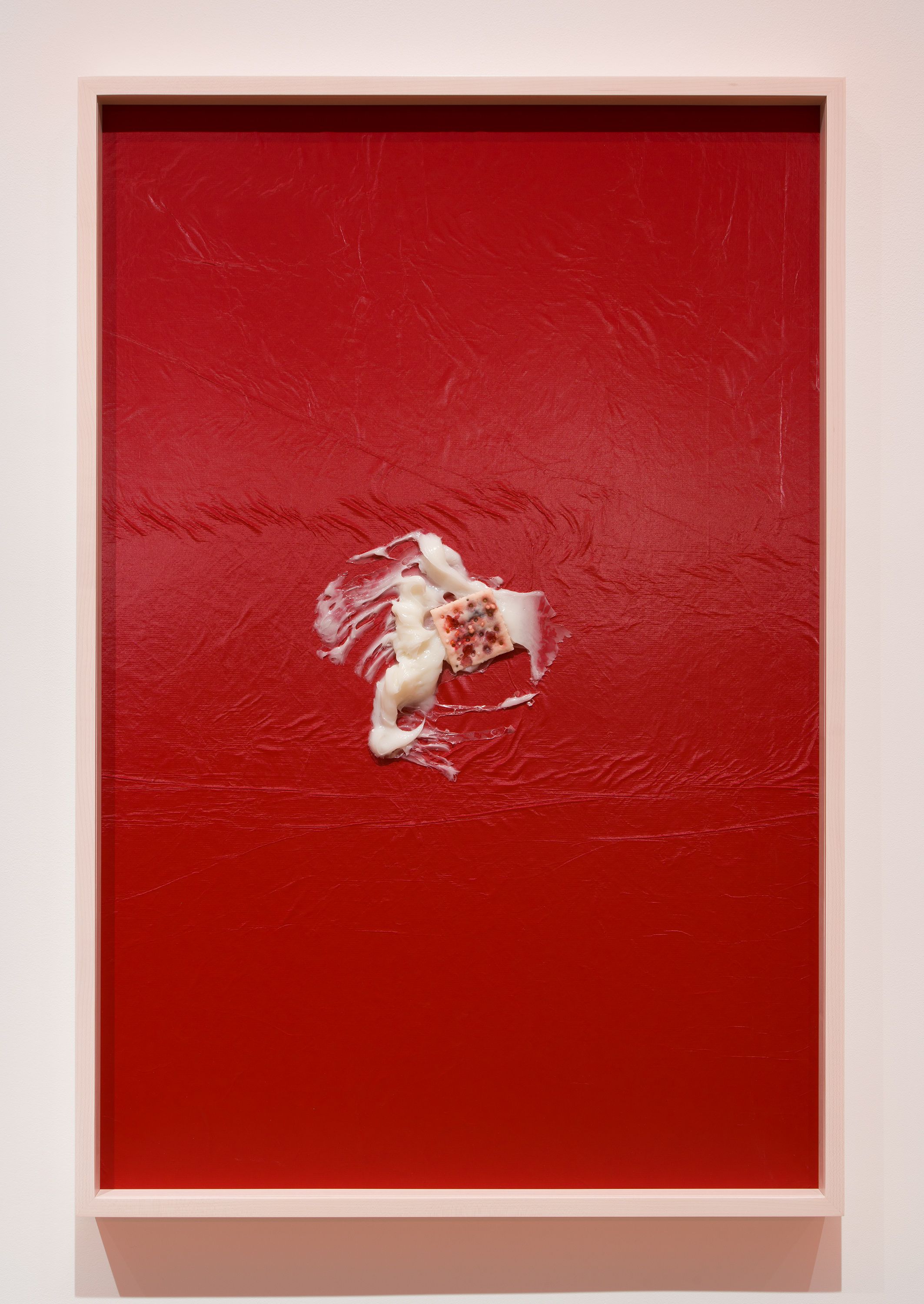

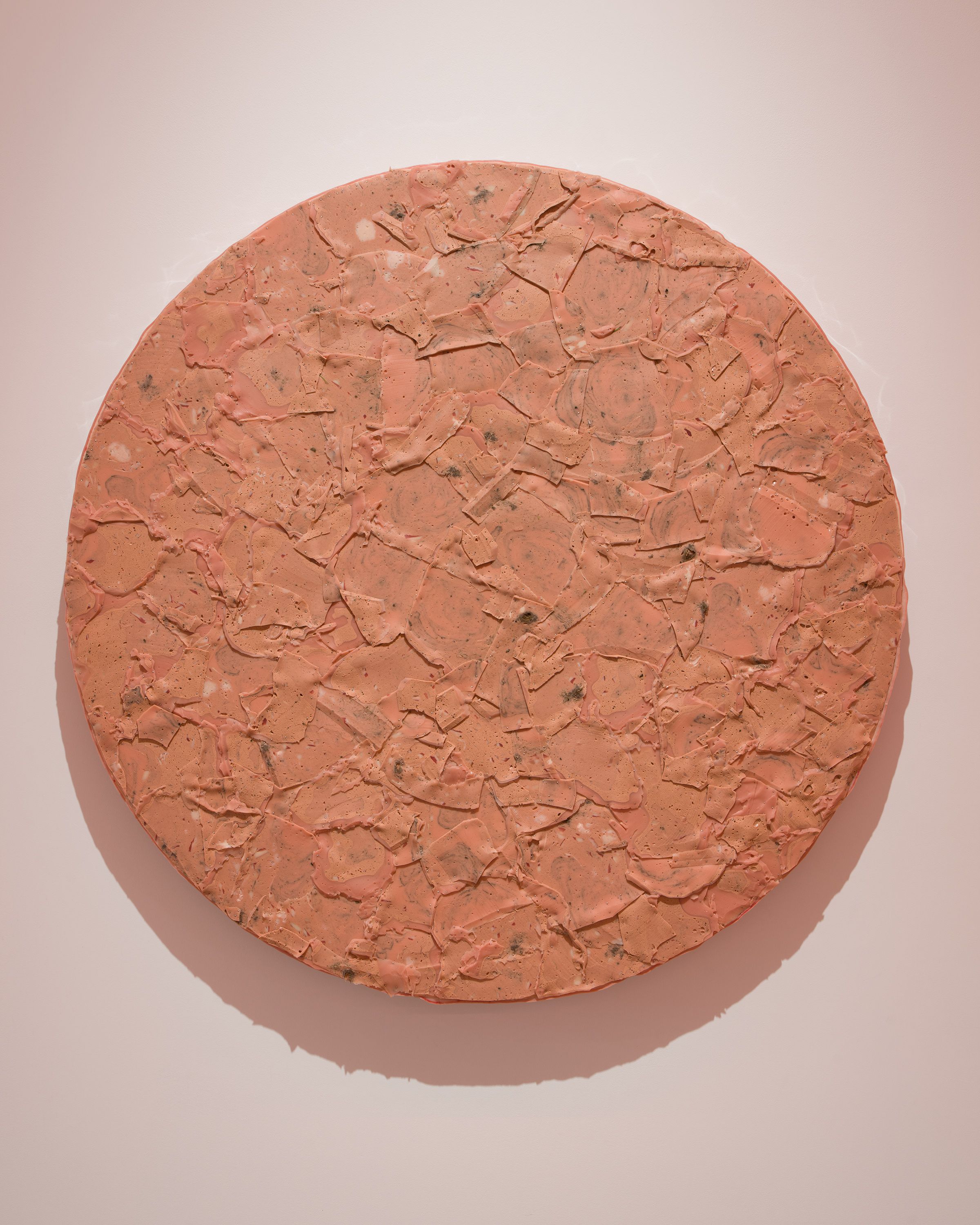

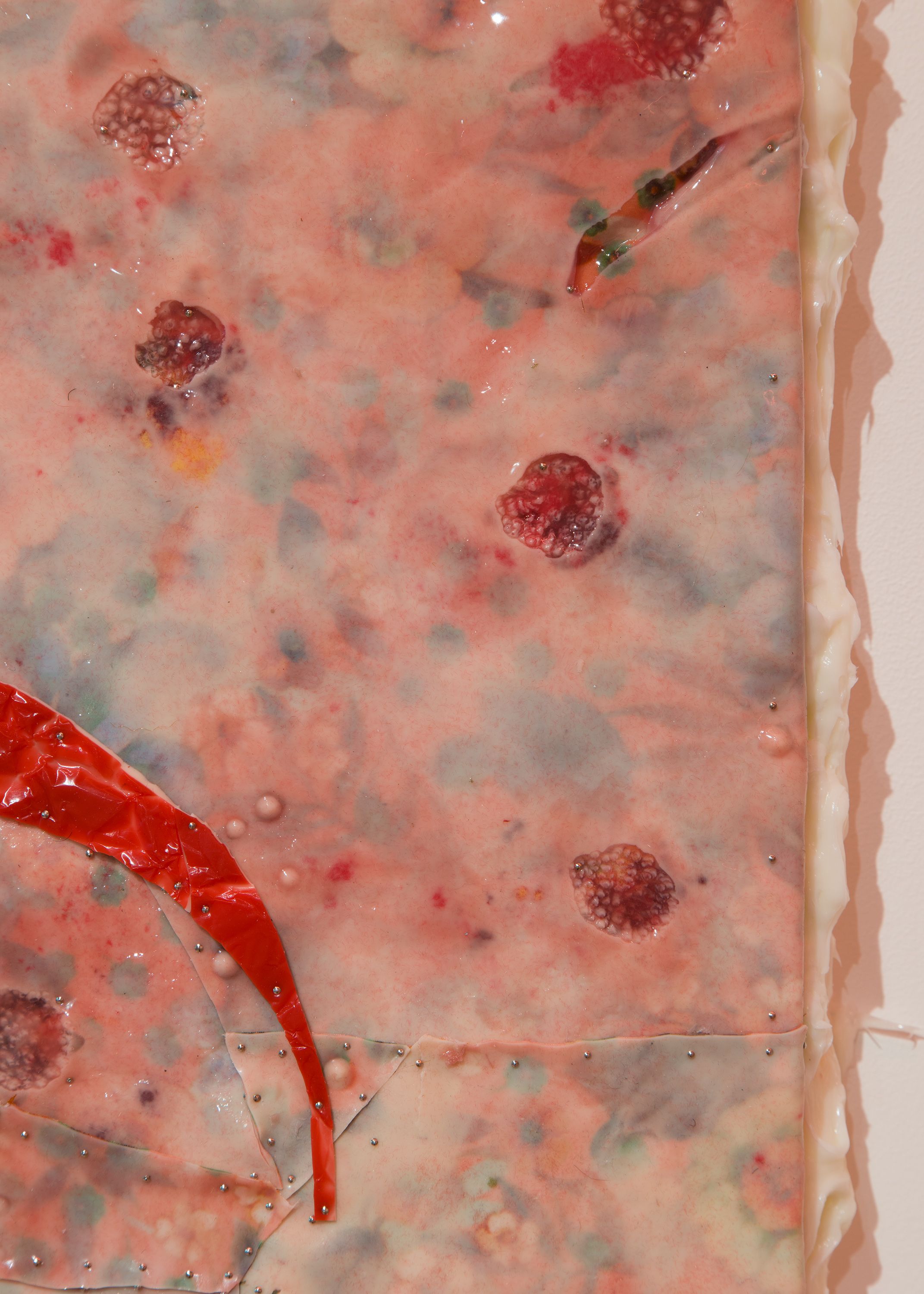

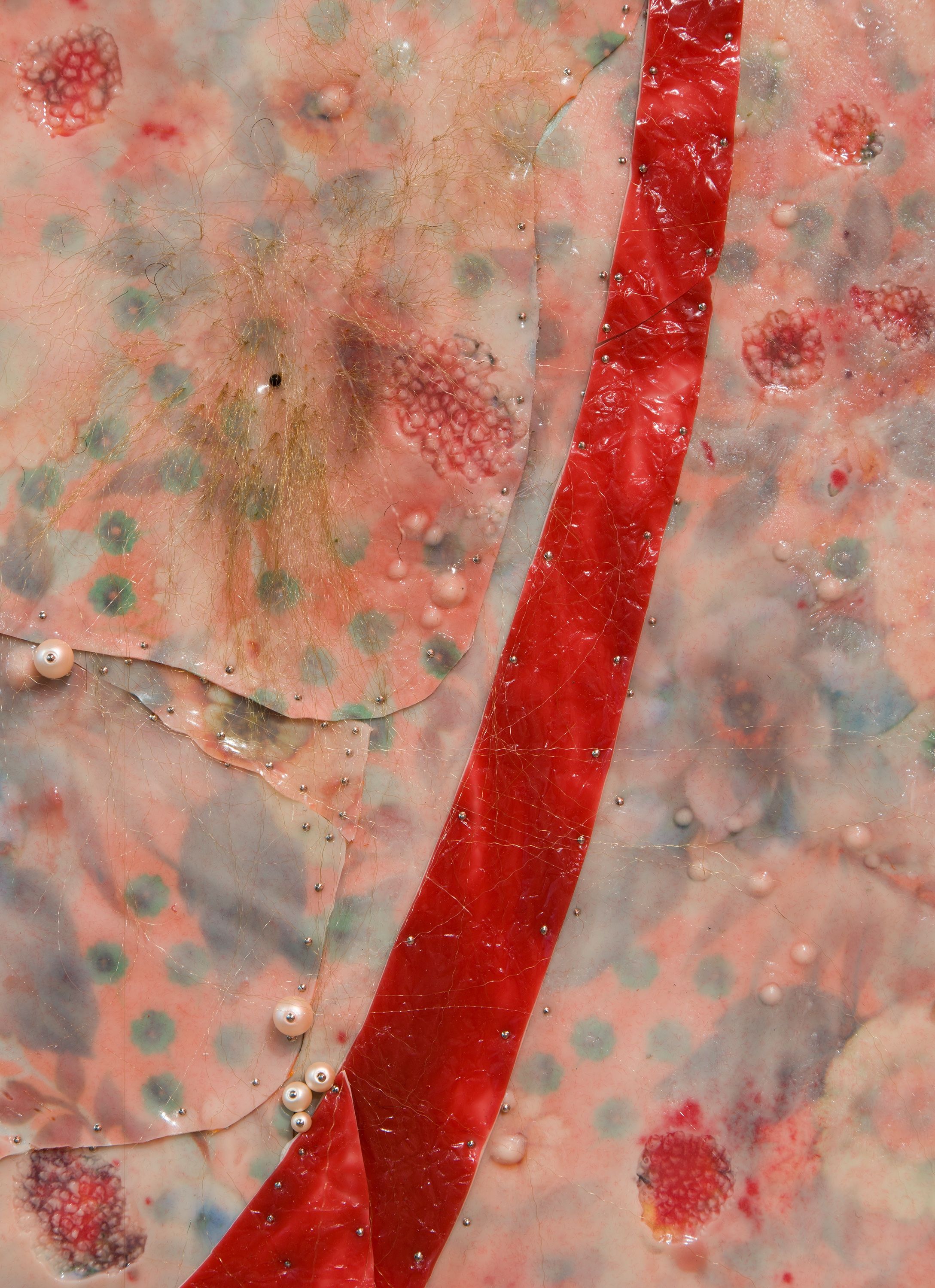

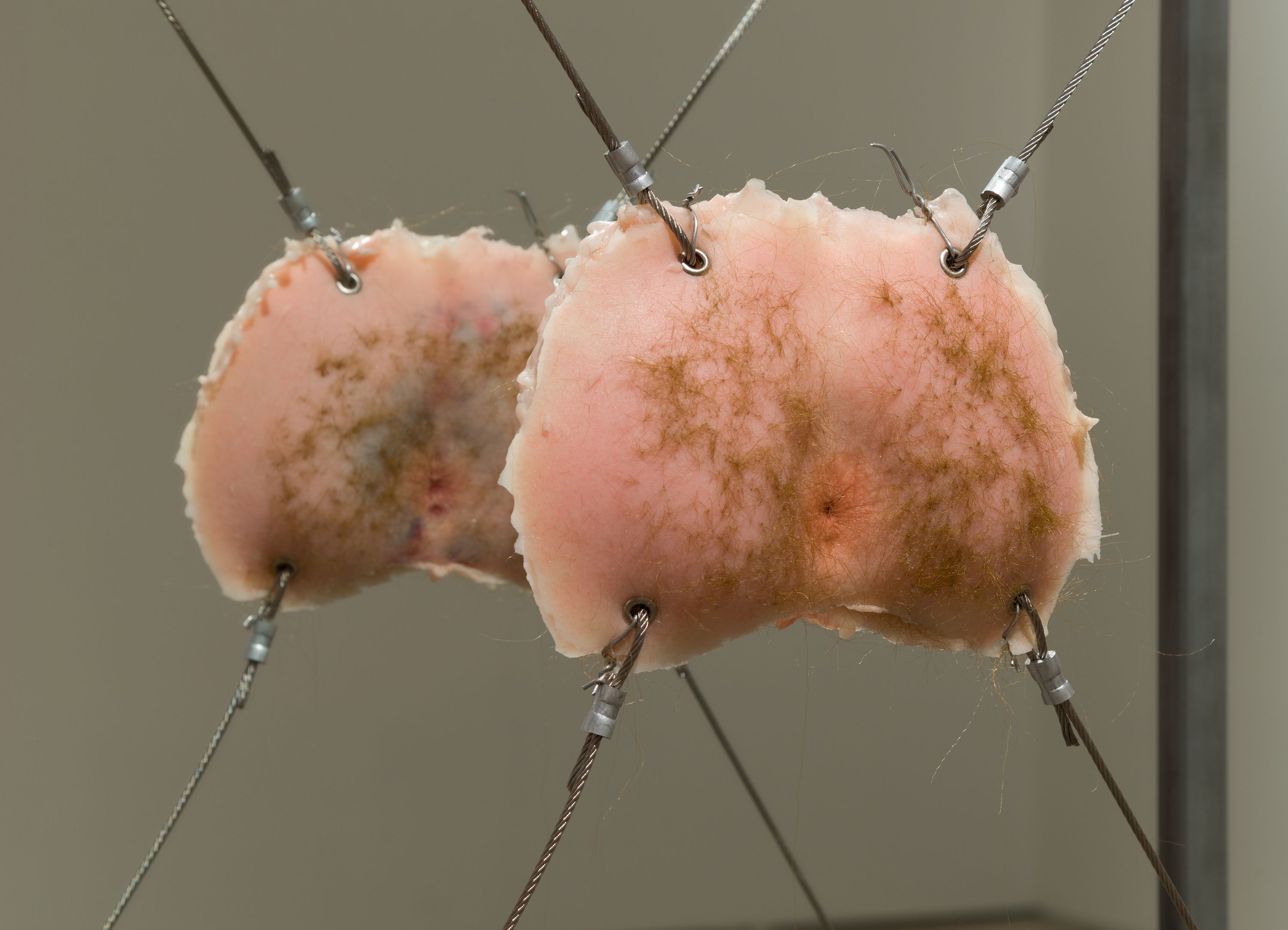

Throughout the exhibition, sculptures made from silicone, beads and hair appear constructed from diseased, pustulating white flesh covered in oozing sores and boils, detailed with ink using a tattoo machine. Several works on view with clown makeup crafted from skin feature bruises and exaggerated facial expressions stretched over floral fabric; performative masks coated in a slick sheen of sweat. A series of crackers set against an expanse of red material appear, upon closer look, to be made of white skin festering with disease. Cobra painted each cracker to correspond coloristically with portraits of the first nine Presidents of the United States. Beneath are thick smears of semen-colored paste the consistency of mayonnaise. When European nations began voyages to colonize other regions including the “New World,” they brought contagion with them, spreading disease across vast nations that held no immunity to the foreign pathogens.

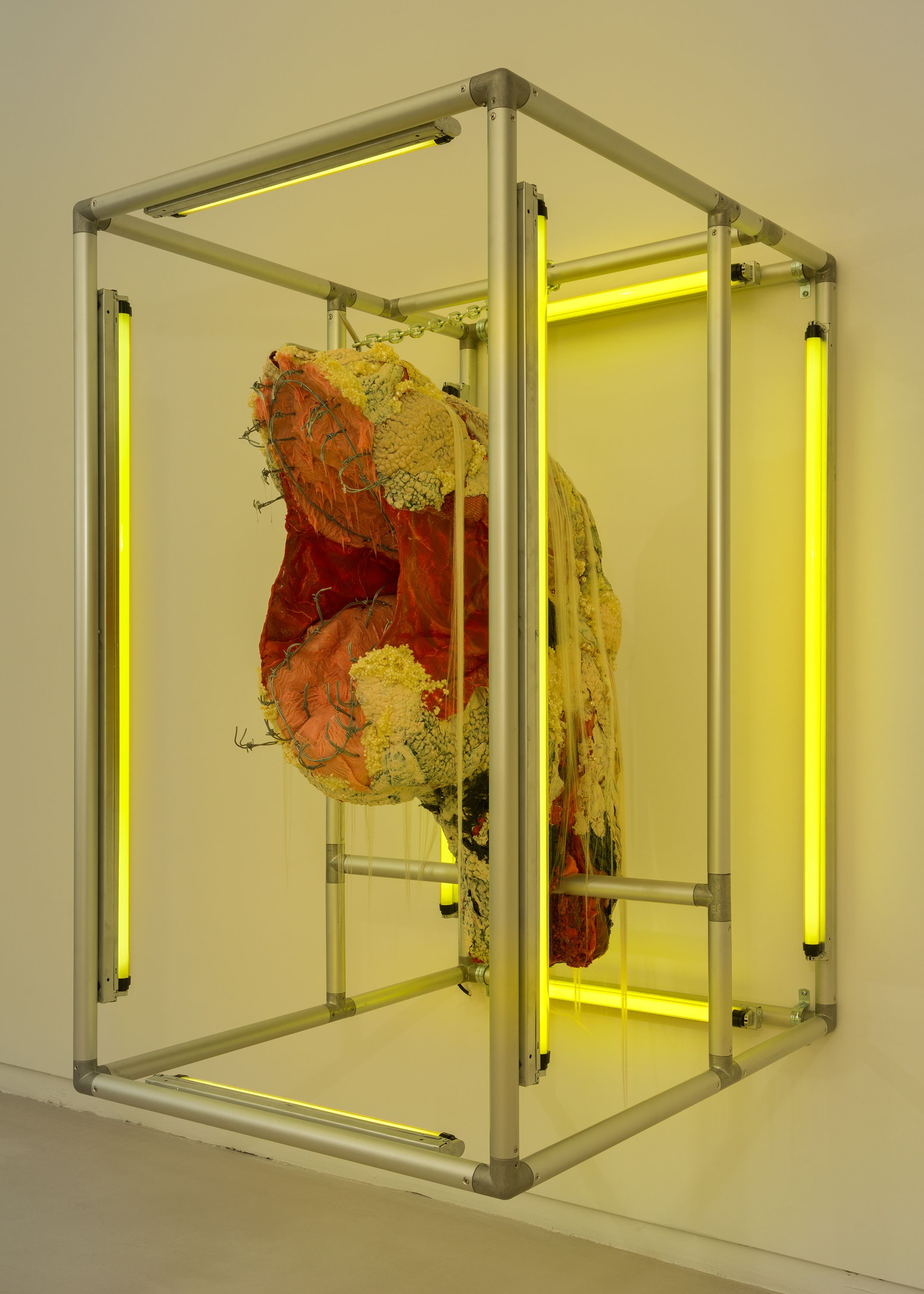

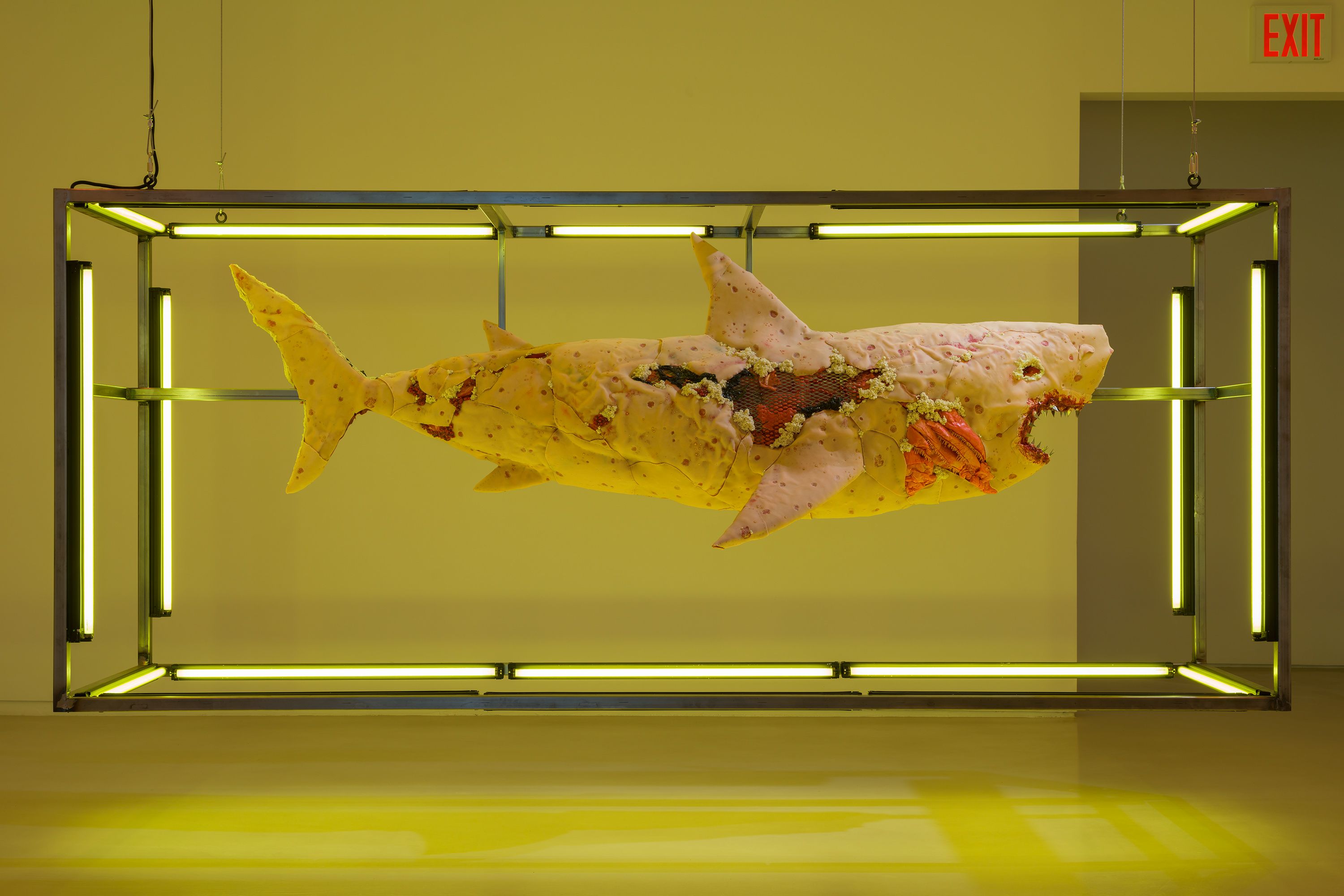

In her most major sculptural work to date, Cobra constructed a male great white shark covered in decaying white flesh and suspended in a 13-foot-long cage of fluorescent lights. When You Are Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea uses the grand gesture of animal trophy display as a metaphor for consumption and capture, as well as references the weaponization of sharks by slave ship captains. These captains would strategically keep sharks close to prevent the insurrection of their captives. Sharks and fear itself, like disease, were weaponized by whiteness.

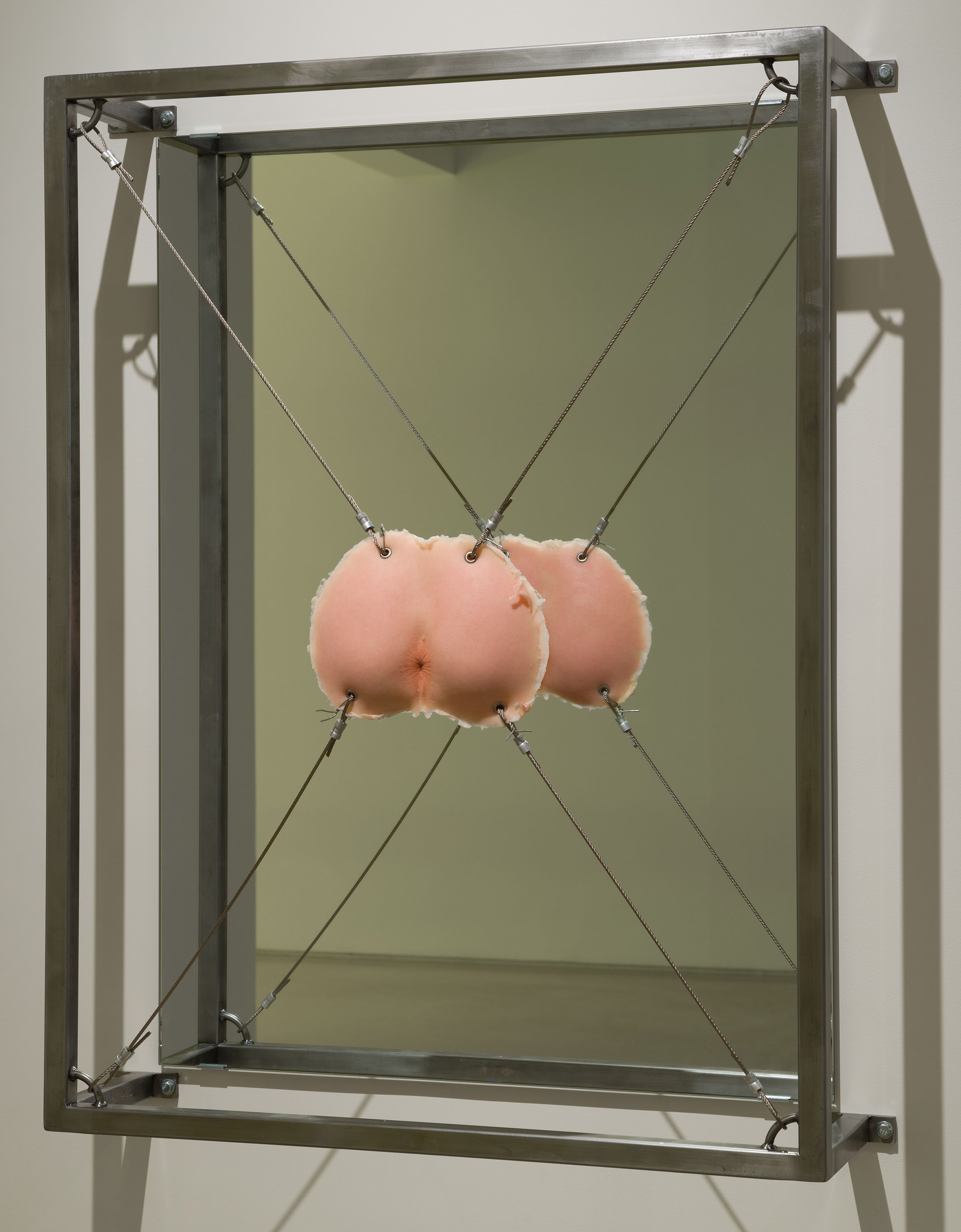

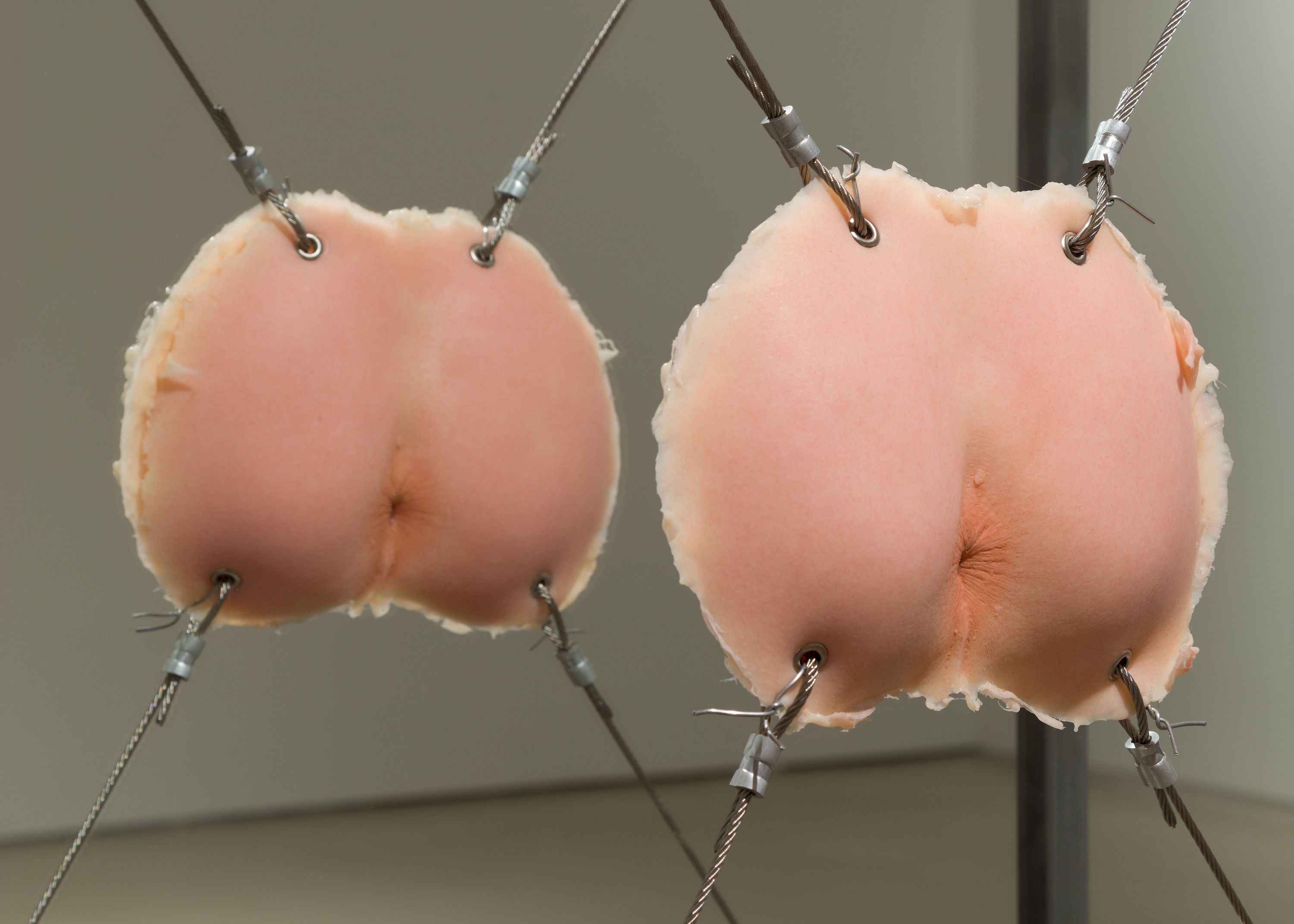

The heavy histories that King Cobra points to in White Meat are devastating, but it is the perverse and uncanny nature of whiteness’s elusive subjectivity that is reflected most clearly within the humorous grotesqueries that rampage across the exhibition: a silicone head of J. Marion Sims run through a deli slicer, an oversized necklace nailed to the wall with scalped blond dreadlocks dangling like charms, and silicone casts of assholes displayed like bits of jewelry. White Meat reveals itself as a cathartic laboratory for unveiling, reckoning with, and dissecting whiteness.

______________________________________

[1] Miguel Gutierrez, “Does Abstraction Belong to White People?,” BOMB Magazine, November 7, 2018.

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, Swarovski crystals, barbed wire, hair weave, fluorescent light, aluminum, steel

60.5 x 36 x 45 in

153 x 91.5 x 113.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, Swarovski crystals, barbed wire, hair weave, fluorescent light, aluminum, steel

60.5 x 36 x 45 in

153 x 91.5 x 113.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, Swarovski crystals, barbed wire, hair weave, fluorescent light, aluminum, steel

60.5 x 36 x 45 in

153 x 91.5 x 113.5 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, dirt from J. Marion Sims's grave, deli slicer, acrylic

17.5 x 20.5 x 18 in

44.5 x 52 x 45.5 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, dirt from J. Marion Sims's grave, deli slicer, acrylic

17.5 x 20.5 x 18 in

44.5 x 52 x 45.5 cm

silicone, flocking powder, AstroTurf

7.5 x 6 x 6.5 in

19 x 15 x 16.5 cm

silicone, flocking powder, AstroTurf

7.5 x 6 x 6.5 in

19 x 15 x 16.5 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel nails on Tyvek

37 x 25 in

93.5 x 63 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, hair weave, epoxy resin, beads, razor blades, fluorescent lights, steel

67 x 156 x 42 in

170 x 396 106.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, hair weave, epoxy resin, beads, razor blades, fluorescent lights, steel

67 x 156 x 42 in

170 x 396 106.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, hair weave, epoxy resin, beads, razor blades, fluorescent lights, steel

67 x 156 x 42 in

170 x 396 106.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, hair weave, epoxy resin, beads, razor blades, fluorescent lights, steel

67 x 156 x 42 in

170 x 396 106.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, hair weave, epoxy resin, beads, razor blades, fluorescent lights, steel

67 x 156 x 42 in

170 x 396 106.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, hair weave, epoxy resin, beads, razor blades, fluorescent lights, steel

67 x 156 x 42 in

170 x 396 106.5 cm

silicone, urethane foam, pearls, hair weave, epoxy resin, beads, razor blades, fluorescent lights, steel

67 x 156 x 42 in

170 x 396 106.5 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, dirt from J. Marion Sims's grave, steel pins, and urethane foam on wood panel

40.5 x 40.5 x 3 in

102 x 102 x 7.5 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, dirt from J. Marion Sims's grave, steel pins, and urethane foam on wood panel

40.5 x 40.5 x 3 in

102 x 102 x 7.5 cm

silicone, fabric, hair weave, pearls, glass crystals, steel pins, and urethane foam on wood panel

42.5 x 32 x 3 in

108 x 81.5 x 7.5 cm

silicone, fabric, hair weave, pearls, glass crystals, steel pins, and urethane foam on wood panel

42.5 x 32 x 3 in

108 x 81.5 x 7.5 cm

silicone, bricks, glass shards, aluminum tins, urethane foam, acrylic

8.5 x 27.5 x 28.5 in

21.5 x 70 x 72 cm

silicone, bricks, glass shards, aluminum tins, urethane foam, acrylic

8.5 x 27.5 x 28.5 in

21.5 x 70 x 72 cm

silicone, fabric, hair weave, pearls, glass crystals, steel pins, and urethane foam on wood panel

42.5 x 32 x 3 in

108 x 81.5 x 7.5 cm

silicone, fabric, hair weave, pearls, glass crystals, steel pins, and urethane foam on wood panel

42.5 x 32 x 3 in

108 x 81.5 x 7.5 cm

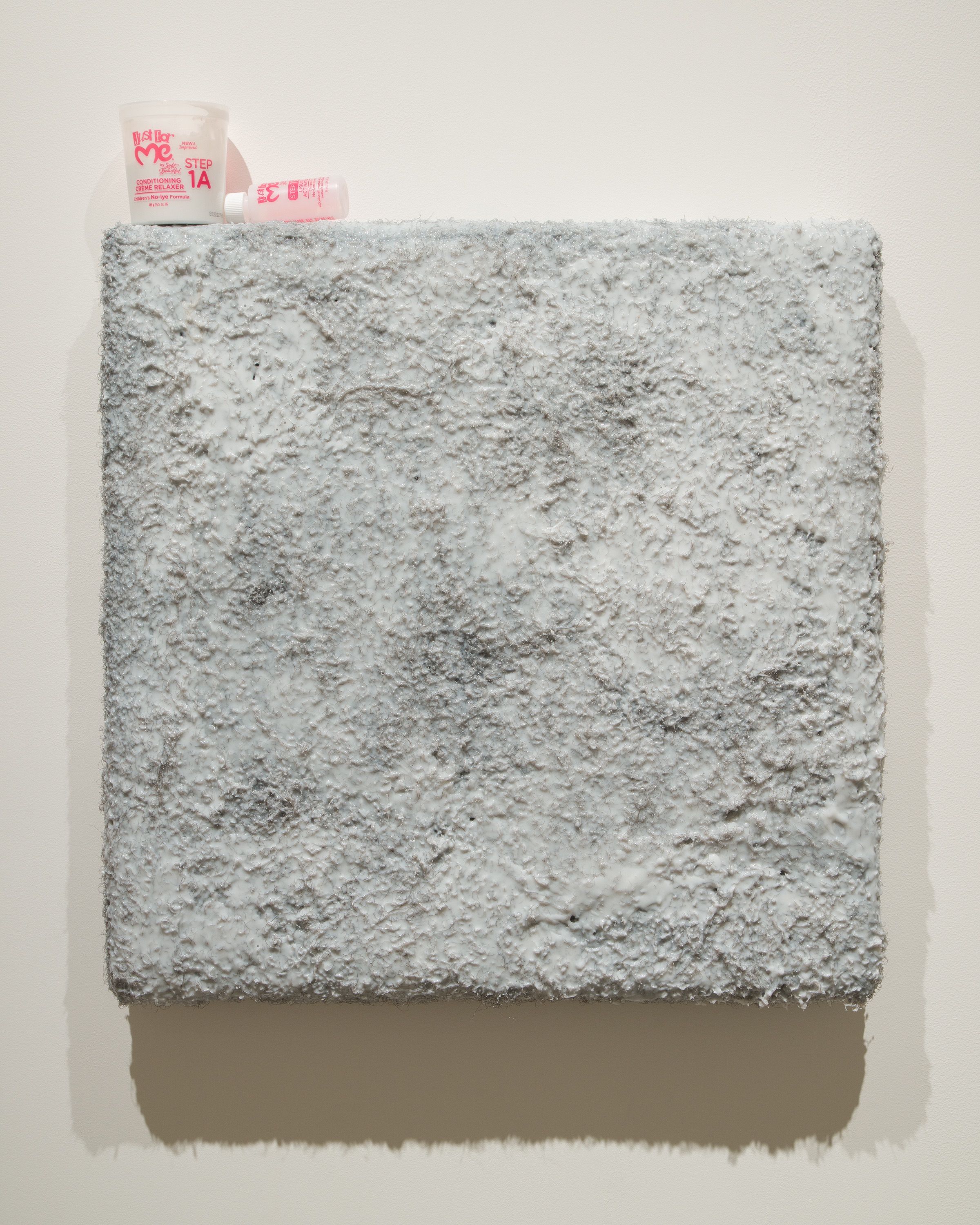

synthetic brown leather, hair weave, silicone, Just for Me Step 1A, Just for Me Step 1B, and urethane foam on wood panel

29 x 25 x in

73.5 x 63.5 x 9.5 cm4

synthetic brown leather, hair weave, silicone, Just for Me Step 1A, Just for Me Step 1B, and urethane foam on wood panel

29 x 25 x in

73.5 x 63.5 x 9.5 cm4

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel cable, mirror, steel frame

40 x 32 x 9 in

101.5 x 81.5 x 23 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel cable, mirror, steel frame

40 x 32 x 9 in

101.5 x 81.5 x 23 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel cable, mirror, steel frame

40 x 32 x 9 in

101.5 x 81.5 x 23 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel cable, mirror, steel frame

40 x 32 x 9 in

101.5 x 81.5 x 23 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel cable, mirror, steel frame

40 x 32 x 9 in

101.5 x 81.5 x 23 cm

silicone, flocking powder, tattoo ink, steel cable, mirror, steel frame

40 x 32 x 9 in

101.5 x 81.5 x 23 cm

silicone, hair weave, tattoo ink, steel chain

124 x 72 x 5 in

315 x 183 x 12.5 cm

silicone, hair weave, tattoo ink, steel chain

124 x 72 x 5 in

315 x 183 x 12.5 cm

hair weave

480 x 2 x 2 in

1,219 x 5 x 5 cm